“Believe me, the painting doesn’t do him justice. He’s worse than me.”–Lupin, describing General Headhunter.

“Believe me, the painting doesn’t do him justice. He’s worse than me.”–Lupin, describing General Headhunter.

To keep his nation’s treasury out of the hands of thieves, the king of Zufu moved his nation’s gold reserves to a safe house on Drifting Island. After a coup topples the heads of the king and his son, Prince Pannish, Zufu and the Drifting Island fall into the hands of General Headhunter. The general has spent lucre and lives trying to break into Drifting Island’s vaults, only to be frustrated at every turn. Now Lupin and his gang have turned their talents to the task. Getting to Drifting Island is simple enough, even while dodging General Headhunter’s agents, Inspector Zenigata, and double agents, such as the prince’s lover, Oleander. But as Drifting Island’s mechanical defenses continue to stymie Lupin and his gang, the nation rises in revolution. For Prince Pannish has returned to take his country back from General Headhunter.

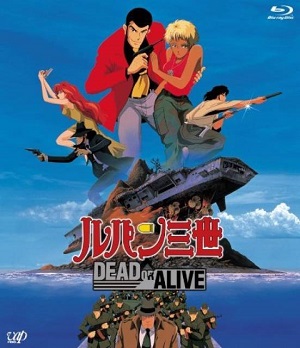

The fifth Lupin III theatrical movie, 1996’s Dead or Alive had been plagued with issues throughout its production. With no one else willing to helm the project through the short production schedule, Lupin III manga artist Monkey Punch stepped up to lead. Quickly overwhelmed, he relied heavily on his staff, generally staying out of their way while the deadline approached. What should have been a disaster instead turned into a solid action film, although one with the slower pacing of manga instead of the relative frenzy of Hollywood. Dead or Alive steers the series back towards its darker roots without abandoning the formula that established the franchise. With the theatrical animation quality and the shift in tone, Dead or Alive stands out from the the TV specials that propelled the franchise through the 1990s.

In a tradition stretching back to the dime novels of Arsène Lupin and beyond, every adventure hero eventually stumbles into a caper square in the realm of science fiction. In Dead of Alive, its Lupin’s turn as he struggles to find a way around the computers, nanomachines, and robots that bar his way to the treasure on Drifting Island. In hindsight, the plausibility of such defenses no longer assists. Gold is too soft and heavy to make a convincing building block for nanomachines, and there just isn’t enough free gold on the planet to supply the machinery. The nanomachines act as near-instant assemblers, a variation of the speedy grey-goo nightmare that hung over popular portrayals of nanomachines at the time. (As is common with every new technology since the Romantic period, a new version of Frankstein’s monster unique to it appears.) But while future discoveries and engineering have battered the plausibility, the nanomachines and computer tech serve as a MacGuffin for the conflict between Lupin and General Headhunter over the treasure and over Oleander’s heart. Which is a good thing, since most adventure science fiction ages poorly as technology never develops in the manner that these five years in the future tales predict.

Fujiko and Oleander both play to the growing action girl trope. Oleander has the short hair, tan skin, and short skirt common to female brawlers of 1990s anime. She even has the chance to show off a move or two when two thugs try to corner her in an alley. She’s competent, but not the one-woman-army that can change the course of a battle like current pixie-fu waifus can. Oleander does need help from Lupin and his whole gang. And despite her short hair, she still maintains her femininity and vulnerability, two more characteristics that distinguish her from the Hollywood Action Girls. As Lupin III‘s answer to Catwoman, Fujiko continues to show her prowess with sneaking, firearms, and fighting. But with her Japanese background and her glamorous portrayal, one might expect her to demonstrate karate or aikido. Instead, she uses joshi wrestling skills, for in 1996, women’s wrestling (or joshi to distinguish it from the American women’s “style”) was at the peak of popularity and match quality in Japan. Popular enough to be mainstream and glamorous enough to attract the attention of a female audience, it comes as no surprise that a Japanese glamour girl like Fujiko would keep up with the current trends. But with the joshi about to crash, Fujiko’s association with the sport would not last. But like many a 90s anime girl, she will continue to show uniquely female approaches to fighting instead of adopting the growing masculinity of the West. However, this did not keep the West from exploiting these action girls towards their agenda. Funimation’s dub replaces Jigen’s normal criticizing of Fujiko with more favorable, flattering comments. While Funimation has come under recent criticism for politicizing their dubs in recent years, this practice has been in effect since at least 2005, when the Dead or Alive dub was released.

Despite Monkey Punch’s rather hands-off approach to directing, Dead or Alive bears much of his influence. He only worked directly on the opening scene, which has Lupin crashing a prison yard reenactment of The Most Dangerous Game. With the disguises, double-crosses, and Lupin’s glee in the misfortune of others, this short sequence might be the closest to an animated Lupin manga chapter seen in the 50 year franchise. But while Monkey Punch wisely let others do their jobs rather than blunder about and make changes in his ignorance, he did insist on a few rules. Zenigata is at his most competent here, capturing Lupin, seeing through decoys, and stomping his attackers in a fight. Where Zenigata had earlier been a cartoonish Tom to Lupin’s Jerry, in Dead or Alive, he shows off the skills that make him Lupin’s nemesis and equal. The tone and visuals are darker, as befitting the first chapters of the manga. This is reflected in Lupin’s shirt, which is black instead of blue, a sign throughout the franchise that someone is bound for a messy end. Lupin’s ruthlessness returns, as he overthrows General Headhunter’s reign just to get the treasury on Drifting Island. And most importantly, unlike in previous adventures, Lupin and his gang must take home the treasure, a long time mainstay of the manga that has fallen to the wayside. Even the musical direction alludes to Monkey Punch’s original vision for the series. While most of the time, it follows the melodramatic style of 90s action anime, the first chase sequence on Drifting Island instead echoes the soundtrack of the Merry Melodies and Tom & Jerry shorts that inspired the Lupin III manga.

But while Monkey Punch’s stamp is apparent in Dead of Alive, he does not overthrow the Miyazaki formula that guided the franchise for close to twenty-five years at the time of release.1 Lupin still has the heroic goal that Hayao Miyazaki insisted every adventure have. Even as Lupin uses “Prince Pannish’s” return to secure Oleander’s assistance, he also uses it to topple General Headhunter’s oppressive regime–and gives Oleander closure by killing the man who killed her lover. Also, while Oleander is the same sort of curvy blonde that filled the pages of the Lupin III manga, she avoids the negligee and nudity shots that typify Monkey Punch’s works.2 Despite her tough exterior, Oleander is still the same type of good-hearted love interest in the mold of Castle of Cagliostro‘s Clarise and The Fuma Conspiracy‘s Murasaki. While part of Monkey Punch’s reluctance is tied to the director’s job overwhelming him, he also recognized Miyazaki’s work as a differing but valid interpretation of Lupin and his gang. And its the Lupin-as-hero vision that made the franchise a success.

But while Monkey Punch’s stamp is apparent in Dead of Alive, he does not overthrow the Miyazaki formula that guided the franchise for close to twenty-five years at the time of release.1 Lupin still has the heroic goal that Hayao Miyazaki insisted every adventure have. Even as Lupin uses “Prince Pannish’s” return to secure Oleander’s assistance, he also uses it to topple General Headhunter’s oppressive regime–and gives Oleander closure by killing the man who killed her lover. Also, while Oleander is the same sort of curvy blonde that filled the pages of the Lupin III manga, she avoids the negligee and nudity shots that typify Monkey Punch’s works.2 Despite her tough exterior, Oleander is still the same type of good-hearted love interest in the mold of Castle of Cagliostro‘s Clarise and The Fuma Conspiracy‘s Murasaki. While part of Monkey Punch’s reluctance is tied to the director’s job overwhelming him, he also recognized Miyazaki’s work as a differing but valid interpretation of Lupin and his gang. And its the Lupin-as-hero vision that made the franchise a success.

While Monkey Punch and his staff managed to complete Dead or Alive under the demanding schedule, it would be 17 years before the next Lupin movie appeared in theaters. This is a shame, for Dead or Alive showed that the adventures of the master thief could still be successfully adapted to feature length stories. Future theatrical would instead find refuge in chaining shorter, more episodic stories into a feature, and the TV specials rely on a more manic pace periodically interrupted by commercials. Dead or Alive also serves as an excellent entry to the franchise, as all the main relationships are present without the Flanderized clownishness seen in the TV specials. Those who wish to discover what anime was in its heyday before the experiments with CG, moe, and visual novel storytelling should give Dead or Alive a try, as should anyone looking for a satisfying adventure.

Footnotes

- As of 2017’s The Bloodspray of Goemon Ishikawa, Miyazaki’s legacy on the franchise continue to this day, and can be seen as a permanent fixture of the series.

- Monkey Punch even has one of his villains say as much to Fujiko as he feels her up in Chapter 4 of the Lupin III manga, “Reveal Her True Nature”.

The fact that none of these embedded images can be viewed in their own tabs is driving me crazy…

Monkey Punch only directed the opening sequence and it’s a shame because it’s the best part of the film; it’s probably his best intro the series’ history. Monkey Punch’s stamp maybe in the story but everything is too grounded in the reality of an action film. There’s almost none of the black humor and surrealism that made his stories so much fun.

This text was copy and past here:

http://thepulparchvist.blogspot.com/2017/08/50-years-of-lupin-iii-dead-or-alive.html

without credit.

I don’t know if perhaps you have published in 2 different sites, but if not, you should know about the copy.