A. Merritt Defends the Scientific Accuracy of his Stories

Thursday , 9, March 2017 Appendix N, Before the Big Three 8 Comments You know the story. In the early days of science fiction, nobody really cared about getting the science right. But then John Campbell came along and changed all that, and a Golden Age ensued.

You know the story. In the early days of science fiction, nobody really cared about getting the science right. But then John Campbell came along and changed all that, and a Golden Age ensued.

It’s bunk.

Science fiction authors were concerned with scientific accuracy even in the bad old days. And there were plenty of readers cruising the letter columns back then demanding more of it. Here is A. Merritt, an author read by millions, answering just such people in 1932:

Now and then I read a letter in your “Argonotes” expressing doubt as to the scientific accuracy of this or that in my stories, Now and then I read letters from people who quite simply and frankly say they don’t like them. With the latter, I haven’t the least quarrel. If one doesn’t like something, I can’t, for the life of me, see why they shouldn’t say so. As the old rhyme goes—“Some like their pudding hot, Some like it cold, Some like it in the pot, Nine days old.” The Lord knows everybody is entitled to pick his own pudding—prohibitionists to the contrary. I pick mine.

But I am a bit sensitive concerning criticisms of my scientific accuracy.

I write entirely to please myself, what pleases me, as I please and when I please. I honestly don’t take into consideration whether what I write will please others. That isn’t any “high hat.” I just can’t write any other way. I know that some will like what I’ve written. And I warm up to those unknown but sympathetic souls. I know they’re people I’d like to talk to, and who probably would get some enjoyment out of talking to me. As for the others, well, there are any number of entirely worthy folk who wouldn’t enjoy talking to me at all, and who would leave me quite cold if I met them. And they are probably just as interesting to others, or as interested in others, as those who like what I write would be in me or to me. But if I had to think, every sentence or idea—“Will they like this or won’t they?”—I couldn’t write anything. So I write what I like, and when I read that someone likes it, too, I say—“I’m damned glad.” And when they write they don’t, I say—“Well, why should you?” And that’s that.

But the question of accuracy is entirely different. There was some criticism of “The Snake Mother.” Some even called it a “fairy tale.” That was rather funny, because, for example, if all the novelists and playwrights who have rewritten Cinderella could be laid head to foot they would reach to the moon and back. And every so-called “realistic” story can be paralleled in plot by Grimm and Hans Andersen. However, there is not a single scientific statement in “The Snake Mother” that cannot be substantiated. If any one, even at this late date, desires to ask any question about it I will be glad to answer him. Or her.

And now, for the benefit of those who may question, or of my friends who may be questioned about the accuracy of the scientific framework of “The Dwellers in the Mirage,” I would like to say that is entirely sound.

The bulk of criticism, if any, will probably be directed at the idea of the Little People. I refer these critics to the Nineteenth Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, J. W. Powell, Director. In this will be found an exhaustive account of the legends of the Yun’wi Tsundi’, or dwarf race the Cherokees ran across when they came to the “New World” from Asia. It includes evidence of the Little People’s occupancy of certain parts of Tennessee into post-Civil War times. A very able investigator, Mr. James Mooney—see ibid.—is authority for this.

I particularly call the attention of those interested enough to read this report to the significance of the simple account of the visit of a hunting party of the Cherokees to a debased tribe of the Little People in Florida, and its remarkable resemblance to the story of Herodotus concerning the storks and the pygmies. Certainly this is not the kind of story the bigoted missionaries, or perhaps I should just say missionaries, would have told the Indians. It must, therefore, pre-date the arrival of the white plague in America.

As for the Kraken, I myself have seen its symbol carved high on the Andean peaks by hands thousands of years dead, and listened to Indians telling me of the Destroyer of Life.

As for the alternating personality theme, read Dr. J. Morton Prince’s “Dissociation of a Personality” and see how conservative I have been.

The Alaskan valley? None knows how startled I was when last October I read on the first page of the New York Times of the discovery of a tropical valley in that locality where summer reigned even when the outside temperature was forty degrees below zero!

Enough of explanations. I hope your readers will enjoy the tale. Those who do not will find plenty to enjoy in the other pages of your most excellent magazine.

How strange he writes!

I mean, I keep hearing about how this was a dark age when, as Andrew Liptak puts it, men made little room at the table for women in the field of science fiction. And yet A. Merritt writes as if these sticklers for scientific accuracy in his stories may well be female. Why would he do that if the scene was in some sort of overtly self-conscious He-man Women Haters Club™? (I do admit, his crude racism is rather shocking. Calling white people a plague?! Incredible! But you know, people are always saying things that folks from future eras are going to look back and just shake their heads at. You’ve got to expect some of that in any era.)

Anyway, if scientific accuracy wasn’t really all that new when John W. Campbell took charge of the field, what actually changed during the so-called “Golden Age”? That’s easy. The biggest change you’ll see in the transition from Stanley G. Weinbaum to the Campbellian era would be the nigh total eradication of classy dames in space as a result of some sort of weirdly puritanical spasm. It’s kind of creepy, really.

Consider this passage from A. E. Van Vogt’s Space Beagle stories:

In this all-masculine expedition, the problem of sex had been chemically solved by the inclusion of specific drugs in the general diet. That took away the physical need, but it was emotionally unsatisfying.

Say what you want about scientific accuracy, but this sort of thing is just not going to inspire people in droves to bang down the doors of CalTech in order to do the extremely tedious science it takes to actually get us to other worlds…!

The sorts of stories that accomplished that were different. They combined heroism, thrills, wonder, and romance– a heady concoction that appealed to a far broader audience than the more narrowly focused Campbellian science fiction. The appeal was so broad, there were even women like Francis Stevens, C. L. Moore, and Leigh Brackett that wanted to write it, female authors that were positively revered by the fans of their day. But that’s the thing. If you redefine science fiction to specifically exclude A. Merritt and Edgar Rice Burroughs, you end up with a weird narrative about the genre where Mary Shelly invented science fiction and then women were practically barred from writing until Ursula Le Guinn managed to break into the scene.

That’s stupid.

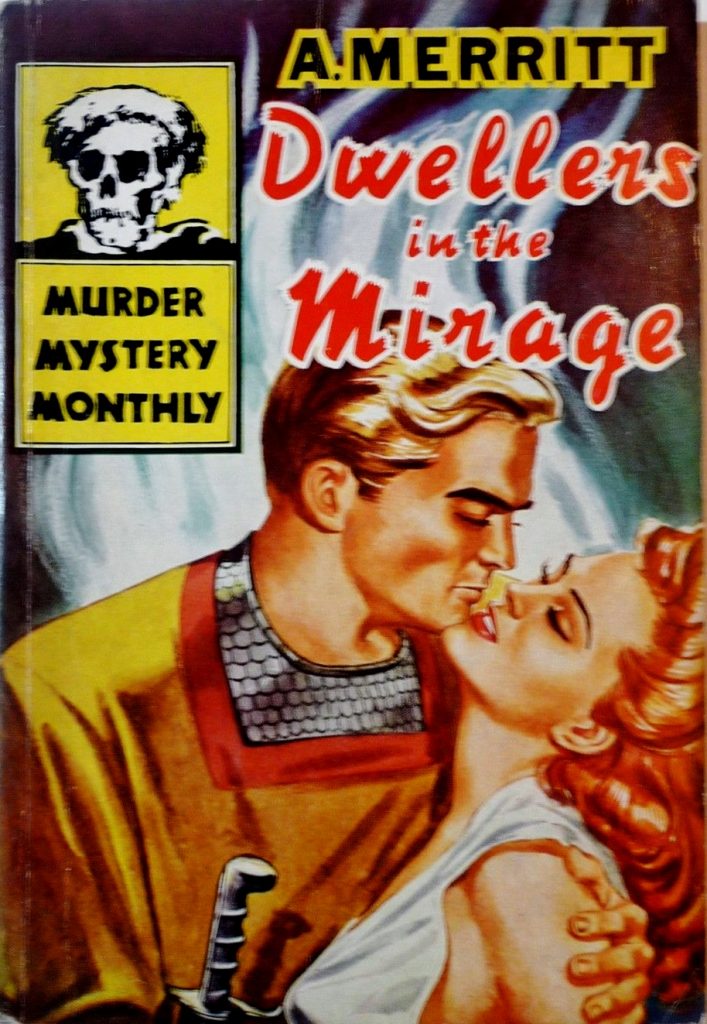

That letter appeared in Argosy while that pulp was still serializing DWELLERS IN THE MIRAGE in early 1932. The novel featured a barbarian protagonist in a lost world where a medieval/Viking culture waged war against (sort of)

Native Americans.

Robert E. Howard created Conan the Cimmerian about a month later. That is not coincidence.

But according to

1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization

Islam invented Sci-Fi, so how could it have been Mary Shelley?

Rod Walker can attest firsthand that if you make an error in a book, especially a historical error, people will track you down and explain at great lengths the crimes you have committed against literature, and indeed, civilization itself.

It is amusing to see that some things have never changed.

Doc Skyskull is a professor of physics/optics at UNC and also a Merritt fan. Here’s what he has to say about some of the science:

“Snake Mother”/FACE IN THE ABYSS:

https://skullsinthestars.com/2009/03/22/a-merritts-the-face-in-the-abyss/

“Dwellers”:

https://skullsinthestars.com/2009/02/22/a-merritts-dwellers-in-the-mirage/

I gnash my teeth and sometimes try, ever so gently, to correct when an author ascribes inaccurate characteristics to a firearm. E.g. “He flicked off the safety on the Glock.”

“The sorts of stories that accomplished that were different. They combined heroism, thrills, wonder, and romance– a heady concoction that appealed to a far broader audience than the more narrowly focused Campbellian science fiction. The appeal was so broad, there were even women like Francis Stevens, C. L. Moore, and Leigh Brackett that wanted to write it…”

Right on. Merritt inspired Andre Norton to hit the typewriter as well. She was never shy about admitting it.

Make A.Merritt Great Again!

I cut my teeth on Edgar Rice Burroughs in the 60s and sharpened them on A.A. Merritt, Otis Adelbert Kline, Robert E. Howard etc. When the more “scientific” stories came around I looked at them as just that science stories without the fiction. They lacked the romance, the heroism, the fantastic allure of the earlier stories. It was like reading a copy of Popular Science with a story. I switched to comics for my heroic inspirations, what a step down.

It sounds like Merritt had his own defintion of science. But times back then were obviously very different from today. These days nobody would give a damn if “little people” was pure fiction or not. But back then authors often felt they had to protect themselves and defend the content of Scientific accuracy in their stories.

The name “science fiction” is still to blame today when someone claims a story is not really science fiction because there is not enough science in the story, or when a story that is not really science fiction is referred to as that just because it contains science.

At least Carl Barks didn’t have to defend himself for creating stories like “Mystery of the Swamp” or “Land of the Pygmy Indians”.

A lot of science fiction writers stopped writing about ancient civilizations on Mars once it was revealed the Surface was lifeless. Even Leigh Brackett (later she would write planetary romance set in other solar systems). Luckily modern writers can do whatever they like with Mars today without anyone complaining about what it looks like in real life.

If I should complain about something myself, it would be when authors of science don’t know anything about the concepts of evolution and treat it almost as if it was magic.

Doc Smith himself felt he had to defend himself regarding the first to Skylark novels:

To all profound thinkers in the realms of Science who may chance to read Skylark Three, greetings:

I have taken certain liberties with several more or less commonly accepted theories, but I assure you that those theories have not been violated altogether in ignorance. Some of them I myself believe sound, others I consider unsound, still others are out of my line, so that I am not well enough informed upon their basic mathematical foundations to have come to any definite conclusion, one way or the other. Whether or not I consider any theory sound, I did not hesitate to disregard it, if its literal application would have interfered with the logical development of the story. In “The Skylark of Space” Mrs. Garby and I decided, after some discussion, to allow two mathematical impossibilities to stand. One of these immediately became the target of critics from Maine to California and, while no astronomer has as yet called attention to the other, I would not be surprised to hear about it, even at this late date.

While I do not wish it understood that I regard any of the major features of this story as likely to become facts in the near future—indeed, it has been my aim to portray the highly improbable—it is my belief that there is no mathematical or scientific impossibility to be found in “Skylark Three.”

In fact, even though I have repeatedly violated theories in which I myself believe, I have in every case taken great pains to make certain that the most rigid mathematical analysis of which I am capable has failed to show that I have violated any known and proven scientific fact. By “fact” I do not mean the kind of reasoning, based upon assumptions later shown to be fallacious, by which it was “proved” that the transatlantic cable and the airplane were scientifically impossible. I refer to definitely known phenomena which no possible future development can change—I refer to mathematical proofs whose fundamental equations and operations involve no assumptions and contain no second-degree uncertainties.

Please bear in mind that we KNOW very little. It has been widely believed that the velocity of light is the limiting velocity, and many of our leading authorities hold this view—but it cannot be proved, and is by no means universally held. In this connection, it would appear that J. J. Thompson, in “Beyond the Electron” shows, to his own satisfaction at least, that velocities vastly greater than that of light are not only possible, but necessary to any comprehensive investigation into the nature of the electron.

We do not know the nature of light. Neither the undulatory theory nor the quantum theory are adequate to explain all observed phenomena, and they seem to be mutually exclusive, since it would seem clear by definition that no one thing can be at the same time continuous and discontinuous. We know nothing of the ether—we do not even know whether or not it exists, save as a concept of our own extremely limited intelligence. We are in total ignorance of the ultimate structure of matter, and of the arrangement and significance of those larger aggregations of matter, the galaxies. We do not know nor understand, nor can we define, even such fundamental necessities as time and space.

Why prate of “the impossible”?

John W. Campbell ended with these Words:

SOME REMARKS ON THE “SKYLARK THREE” AND ABOUT ERRORS. A COMPLIMENT TO DR. SMITH’S STORIES.

Editor, Amazing Stories:

Dr. Smith, in his foreword to “Skylark Three” mentions two errors which he made knowingly. I think I can recognize the astronomical one, at any rate.

Of course, the acceleration of twice 186,000 miles per second, as used in escaping the field of the great “dud” star, as told in “Skylark of Space” was impossible. Nothing could withstand that strain. Further, no gravitational field could be that intense. It would have exactly the effect Dr. Smith describes and allots to the zone of force in “Skylark Three”—it would make a hole in space and pull the hole in after it. Light would be too heavy to leave the planet. The effect on space would be so great as to curve it so violently as to shut it in about it like a blanket. The dud would be both invisible and unapproachable.

The astronomical error? I wonder how Dr. Smith solved the problem of three—or more—bodies? Osnome is a planet of a sun in a group of seventeen suns, is it not? The gravitational field about even two suns is so exceedingly complex that a planet could take up an orbit only such that one sun was at each of the two foci of the ellipse of its orbit, and then only provided the suns were of very nearly the same mass, and stationary, which in turn means they must have no attraction for each other. No, I think his complex system of seventeen suns would not be so good for planets. Celestial Mechanics won’t let them stay there. And I really don’t see why it was necessary to have so complex a system.

Further, I wonder if Dr. Smith considered the proposition of his ammonia cooling plant carefully? The ammonia “cooling” plant works only to transmit heat, not to remove it. The heat is removed by it from the inside of an icebox for instance, and put outside, which is what is wanted. However, it must have some place to dump the heat. In the fight with the Mardonalians, Seaton has an arenak cylinder on his compressor, and runs it very heavily, but if he can’t get the heat outside the ship, and away from it, he wouldn’t cool the machine at all. Since the Mardonalians kept the outside so hot, and the story says the compressor-cooling was accomplished by a water cooler which boiled—some amount of water, too, if it would absorb all the heat of that Mardonalian fleet in any way—and this heat was then merely transferred from outside to inside—where they DIDN’T want it!

Again, in this battle, to protect themselves against ultra-violet radiation, they smear themselves with red paint—presumably because red will stop ultra-violet.

Personalty, I’d have picked some ultra-violet paint—if any were handy as that would reflect the rays. Red wouldn’t affect them at all, so far as I can see—he might as well have used blue. What he wanted, was a complementary color of ultra-violet, and I don’t believe it is red—green is the complement of red. (Green light won’t pass through red glass.)

Dr. Smith invited “knocks” with that foreword of his—I hope I am complying, as an interested reader, and a hopeful scientist. However, my personal opinion has always been that “Skylark of Space” was the best story of scientifiction ever printed, without exception. I have recently changed my opinion, however, since “Skylark Three” has come out.

John W. Campbell, Jr.

Cambridge, Mass.

(This letter from a fellow author is an excellent comment on Dr. Smith’s foreword to “Skylark Three.” But the writer of this letter is himself inclined to deal with and use very large quantities and high accelerations and velocities in his stories. We are going to let your knocks await a reply from Dr. Smith. The Editor does not desire to find himself between the upper and lower millstones represented by an author and his critic. But you certainly make amends for your criticism by what you say about the merit of “The Skylark Stories.” We hope to hear from Dr. Smith.—Editor.)