A Very Brief History of Military Science Fiction

Wednesday , 17, December 2014 Uncategorized 6 CommentsThe air is full of rumours of War. The European nations stand fully armed and prepared for instant mobilisation. Authorities are agreed that a GREAT WAR must break out in the immediate future , and this war will be fought under novel and surprising conditions. All the facts seem to indicate that the coming conflict will be the bloodiest in history, and must involve the most momentous consequences to the whole world. At any time the incident may occur which will precipitate the disaster.

~Preamble to the forecast tale: The Great War of 1892, published in Black and White Magazine in 1891.

The Alien from Above – German Cavalry during the Great War. Possibly the horse is red.

Although Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826) is frequently (and erroneously) credited as the first of many subgenres in science fiction – post-apocalyptic, military science fiction, post-human – it is not only somewhat mislabeled by genre, but it also and most certainly was not the first of its kind. One of the reasons the book was so resoundingly unpopular in its day was because there was nothing new about it – aside from Shelley’s earnest but misguided attempt to weave in biographies of people she otherwise was forbidden to write about. The “last man on earth” had been well-trod ground for decades when The Last Man was published.

And while Shelley’s Frankenstein was adapted for the stage very soon after the novel was published and about eighty years later as an early film for Edison Studios, The Last Man was (rightfully) forgotten for more than a century and a half. After all, Voltaire’s “future war” which underscores the brutality of a village massacre is in many ways a better projection of the future than Shelley’s romantic and Byronesque battles. Hers serve as little more than gallant distractions from her unstoppable worldwide plague of the 21st century, and Candide pre-dated The Last Man by sixty years.

“The play of plays, the great gentleman’s game, which the ladies like them best to play at — the game of War.” – John Ruskin

Frankenstein was Shelley’s earlier, and far more inventive and influential “last man” novel compared to The Last Man. Neither should be considered a forerunner to mil-SF.

So, mil-SF didn’t start with Shelley. Hypothetical military forecasts have been around for a long time, and the “stories” of Sun Tzu and Machiavelli are among the more famous. Predictive fictions – as fiction – appear to develop on the theatrical stage in the early 1800s (again, before even Frankenstein) as a new avenue of expression against the hated foe (typically the English or French, depending upon the loyalty of the playwright’s patron).

But in stories and novels, forecasting really doesn’t explode as a genre until the publication of The Battle of Dorking, a retrospective “account” of the (pretend) invasion of Britain, which was written following the shocking resolution to the Franco-German War and the unification of Germany.

Despite the massive popularity of military forecasting in fiction during the tumultuous 1880s and 1890s, the forecasts themselves missed the predictive mark quite nearly as badly as The Last Man did…and Shelley wasn’t even attempting to forecast!

This is no surprise. Most of the experts in warfare predicted that the Great War would come sooner than it did, and would live up to the glory and speed that its original moniker would suggest. Only the warfare amateurs: Albert Robida, Ivan Stanislavovich Bloch and – of course – H.G. Wells were able to marry the drive for technological advancement and the breakdown of cultural principles with an enormous and decidedly non-Napoleanic death toll in order to more accurately anticipate the reality that would become World War I.

Wells prophesied on martial matters directly with The World Set Free (atomic weapons), “The Land Ironclads” (tanks) and The War in the Air (dogfights and city bombing), but what cements his place as the forefather of military SF is War of the Worlds. It is nearly impossible to look at photos of the alien gas masks and otherworldly, anti-Victorian landscape of blackened trenches and not see how suited it is to Wells’ Martian “Black Smoke,” the “Heat Ray,” and fighting vehicles. Wells’ highly imaginative wars were much better predictors than the “realistic” fictional projections of the day, and mirrored what Bloch also saw (as early as the 1890s): “[E]verybody will be entrenched in the next war….the spade will be as indispensable to a soldier as his rifle.”

Bloch also saw that battles would go on for days instead of hours, and would be mostly indecisive affairs without victory.

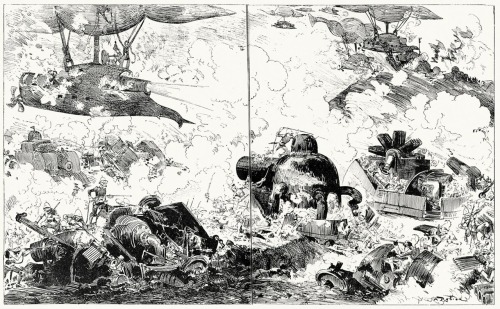

Albert Robida illustrated and anticipated drone missiles and poison gas in future wars in 1887’s La Guerre au vingtième siècle.

However, Wells was seen as a visionary in fiction and philosophy, but –at the time– not of the practical resolution of near-future events, and Bloch–as far as I can tell–was simply ignored on military affairs.

“The new soldier will not be a soldier, but a machinist; he will not shed his blood but will perspire in the factory of death at the battle line.” – Thomas Edison

Mil-SF started with a bang due to Wells’ popularity before the Great War, and it was a chain reaction: the genre was cemented after the war simply on the grounds of it being relevant in addition to being some awfully fun reading.

Between the Wars, pulp action fantasies were fertile territory for mostly smaller scale (i.e. individual soldiers engaged in acts of derring-do against uncomplicated enemies) mil-sf, but in the run-up to WWII, science fiction as a genre had begun to find its legs.

More realistic attempts to forecast farflung warfare start cropping up. This was about the time of Heinlein’s Sixth Column, and was a period when military R&D and science fiction were no longer simply a mutual admiration society, but very nearly the same thing! In fact, the top secret development of radar owes its technical documentation to John W. Campbell. He also “coincidentally” published a short story that predicted atomic bombs. It contained enough details that he was investigated by the FBI. Also at this time a number of science fiction authors were brought to the Philadelphia Naval Yard to analyze defenses and other military projects.

In the 1950s: Starship Troopers, whose importance to the genre can’t be overstated…and certainly won’t be in this brief survey. In the 60s there were books like Glory Road which outline a case for future war, as well as realistic “near-future” mil-sf as exemplified by Jeff Sutton in the hot mini-space battle First on the Moon or the much crunchier Cold War-inspired Apollo at Go.

The Forever War is (I believe) the first mil-sf to take its direct inspiration from active duty in  Vietnam (a conflict which, some might argue, was its own nationalized real-life Science Fiction fantasy in some ways). Joe Haldeman would later be invited to a secret military conference that included professional futurists (which Haldeman described as “stodgy and conservative”), Air Force researchers and pilots (“gratifyingly freewheeling-to-gonzo”) and…a couple of mil-sf writers (“to give the thing a pleasant nut-like flavor.”)

Vietnam (a conflict which, some might argue, was its own nationalized real-life Science Fiction fantasy in some ways). Joe Haldeman would later be invited to a secret military conference that included professional futurists (which Haldeman described as “stodgy and conservative”), Air Force researchers and pilots (“gratifyingly freewheeling-to-gonzo”) and…a couple of mil-sf writers (“to give the thing a pleasant nut-like flavor.”)

Martin Caidin’s Cyborg was the inspiration for the Six Million Dollar Man, and is a very clear demonstration of the relationship between mil-SF and inspiration for real-world military development. Whether or not today’s amputee paralympians owe a debt of gratitude toward Cyborg or not for the eventual development of technology (and being referred to even today as Six Million Dollar Men and Bionic Women), what is clear is that military development has expressly acknowledged the authors of the mil-SF. Engineer Robert Goddard was inspired by Wells to find a way to Mars, and in the process, helped to develop the rocket. Rocket developer Hermann Oberth worked on science fiction movies in the 1920s in order to fund his experiments. One of those films, Woman on the Moon, was seized by the German government for national security purposes.

Fritz Lang’s Woman on the Moon was made in 1929 and confiscated by the German government for divulging too many military secrets.

By the time you get to the last 30 years or so, mil-sf develops best-sellers in techno-thrillers, renewed ties with real world military counsel, and long-running anthologies like There Will Be War, Firefight 2000 and The Future at War. Two different subjects altogether have had significant bearing on the genre: video games (particularly FPS) and independent publishing.

“If there are no formal wars, there is no shortage of combat and death; nor is the situation likely to change.” – Jerry Pournelle

Ultimately, Mil-SF lends itself to non-fiction/fiction mix anthologies like Riding the Red Horse because of its real-world relationship with real world military interest. The next time someone suggests that the birth mother of the genre is The Last Man, tell him that he’s looking at the wrong species.

Start with the First Martian instead.

-

Other famous authors of hypothetical battles:

-

Machiavelli, The Prince

-

Sun Tzu, The Art of War

-

Guilio Douhet, The War of 19–

-

Sir John Hackett, The Third World War: The Untold Story

Cyborg was written by Martin Caidin, not Dean Ing. The book was the inspiration for the Six Million Dollar Man TV series.

I’ve been meaning to write my tome on the history of spec fic for some time now… Science fiction particularly requires military fiction. The genre would be dishonest w/o looking at the way nations exploit technology for their own ends, ending in both cold and hot wars. Great post.

I’m been listening to The Learning Company’s “Masters of War” series, and it is a pretty good primer on military theory. Not a whole lot of depth, but an excellent overview from Sun Tzu to Clausewitz and Mahan to terrorism and COIN operations.

Never heard of “the Last Man”, everything I have read on the subject starts with “The Battle of Dorking” and goes forward from there.

-

The Last Man was completely forgotten until Mary Shelley’s revival in the 1970s. By the 1980s, The Last Man was being credited with all sorts of trend-setting in SF, even though when it was published it was compared unfavorably to Frankenstein and furthermore sold poorly due to its unoriginal concepts.

It treads some familiar ground with electromagnetism and the “boundaries of science” that Frankenstein does much, much better, but the military stuff in it is pure 1820s romance.

In 1803 or so, there were a number of French and British plays that forecast coming military conflicts, but I have not read them. It is possible that they are better forerunners to The Battle of Dorking than The Last Man. I can’t conceive of how they could be worse.

Also to be fair, even the academic sources (which are understandably the ones most favorable to Shelley’s entire body of work) tend to mention The Last Man without much thought and a fair amount of qualification.

I think a comprehensive history of mil-SF really begins in the non-fiction speculations mentioned above (as well as a number of Roman and Greek histories) and I also think that’s why mix books like Riding the Red Horse and There Will Be War are so successful. Simply put, they make sense in a way that simply wouldn’t apply to an anthology of robot stories and robot technology essays (although I’d certainly buy it.)

After all, War Games are a significant component of military strategy. Robot Games are fun, but ancillary to the study of robotics.