A Vital, Overlooked Quality in Fantasy Games (Hint: It’s NOT Story)

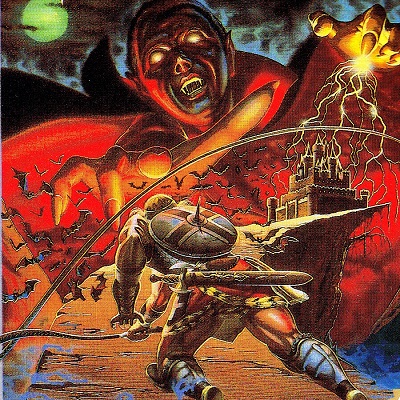

Saturday , 24, March 2018 Games 3 Comments As I mentioned in a previous article, Castlevania is my favorite game franchise, of which I’ve played almost every title. Which one is my absolute favorite? Is it the fantastic Symphony of the Night? Or is it perhaps one of the later Metroidvanias that improved upon the formula, like the superb Portrait of Ruin? Maybe it’s an old-school action platforming classic, like Castlevania III, Super Castlevania IV, or the Japan-only Rondo of Blood? Could it possibly be the overlooked Genesis title, Bloodlines?

As I mentioned in a previous article, Castlevania is my favorite game franchise, of which I’ve played almost every title. Which one is my absolute favorite? Is it the fantastic Symphony of the Night? Or is it perhaps one of the later Metroidvanias that improved upon the formula, like the superb Portrait of Ruin? Maybe it’s an old-school action platforming classic, like Castlevania III, Super Castlevania IV, or the Japan-only Rondo of Blood? Could it possibly be the overlooked Genesis title, Bloodlines?

While I loved all of those, many are shocked to learn my favorite is actually the first Castlevania 64. Yes, the “clunky” early 3D action platformer with supposedly awful camera angles and awkward jumping. I like the game on a purely mechanic level; I think it’s an outstanding early example of the genre, and I never understood the camera complaints considering that the beloved Super Mario 64, released a couple years earlier, was a thousand times worse in that regard.

Yet, what really makes the game special and stand out even compared to all the other outstanding games in the franchise? It’s the immersion, a critical element often overlooked in the fantasy genre.

Immersion is very different than story, and isn’t benefited by the latter at all. In fact, I daresay that if less attention was paid to story and more on immersion, fantasy games would generally improve. CV64, for instance, has a typically forgettable, crappy story. You play as either a Belmont descendant, oddly called Reinhardt Schneider, who goes forth and kills Dracula with a whip, or a Sypha Belnades descendant, oddly called Carrie Fernandez, who goes forth and kills Dracula…with glowing homing orbs.

However, none of this affected how vivid, exciting, and alive the world of the game felt. How much I really felt like I was participating in an adventure, as opposed to amusing myself with a video game.

How did the game achieve such a singular feat? It wasn’t the quality of the graphics. The large, blocky 3D-models were very dated when I played the game in the late 2000’s, and weren’t impressive even when the game first came out in early 1999. Graphics can help with immersion, but they’re not essential, which is one reason why examining older titles is particularly revealing.

Rather, it was the all the little details. For instance, there is a charming villa in the game with splendid Gothic architecture, including a spiral staircase, chandeliers, and photos alongside tastefully done crimson walls. Naturally, the path to this igoes along a charming garden, with lush greens, gorgeous gates and imposing mythological statues. Inside, at the center of the villa is a fountain with a beautiful circular design, and its own small rose garden. That none of this was crisply animated was immaterial. My own imagination filled in the gaps.

All these nuances, one on top of the other, gradually immersed me into the world of the game.

And these details meshed seamlessly with the action itself. None of the stages felt like stages for their own sake, a major difference with the CV 64 re-make/sequel that came out a year later in 2000, Castlevania 64: Legacy of Darkness, that I didn’t care nearly as much for. For instance, those mythological statues turn into Cerberus that attack the player. One’s first sight of the glorious villa and the staircase also has one discovering a vampire climbing the ceiling, the first in the game. And that odd circular room with the rose garden is where one finds the vampire character Rosa, important to the later story and endings.

This all culminates with the game’s final phase, where one climbs up a series of seemingly never-ending steps into the clouds themselves, with stirring, Gregorian chant-inspired music thundering in the background. I can’t think of any other time in a video game where I have been so awestruck and excited at the tremendous adventure and battle I was about to encounter. All this, in a game with skeletons on motorcycles in the 1800s and fetch quests!

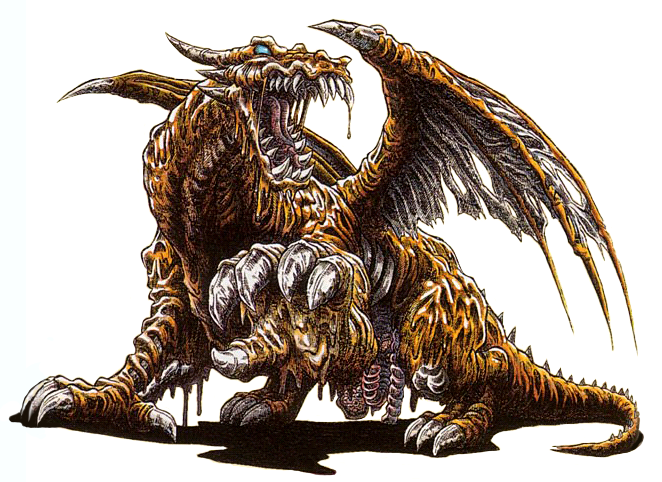

Of course, there are other ways to achieve immersion, and it need not even be a 3D game. Possibly my favorite game ever is Demon’s Crest for the Super Nintendo. One plays as Firebrand/Red Arremer, originally an enemy from Ghosts N’ Goblins, fighting other demons and monstrosities to obtain powerful crests, each of which changes the character into a different form and has other mechanical effects.

The game has nice details, but nothing exceptional. And yet, through a combination of its music, visuals, and the stages themselves, one eventually becomes immersed in this dark demon world. One of the most memorable moments is the player’s hauntingly lonely passage through the overall map, flying through what looks like a dead, mostly deserted world, with only powerful evil populating it in hidden strongholds. The player feels all alone, with only stirring sadness to accompany him.

The wide variety of rich, lush mythological monsters helps, too.

The very first screen of the game has one taking on an enormous skeleton dragon which is too gigantic to be displayed in full. This is the type of monster one might expect to encounter as a final boss of the game, but here, it’s the first enemy of any kind. He is relatively easy to defeat, but successive enemies become harder and harder. Thus, the difficulty is immersive, as how late in the game a boss is actually IS a sign of how challenging he is.

Not bad for the game’s first enemy!

This is perfectly illustrated with the secret, hidden final boss of the game, the Dark Demon. Ordinarily, there are 3 endings in the game; one bad, one middling, and the final, true, good ending. However, after the latter, if one waits on the final screen, a secret code will reveal itself. Entering it will allow the player to face one of the most gorgeously evil, well-designed bosses I’ve ever seen in a 2D game to this day. And his awesome look goes hand-in-hand with his brutal difficulty, complex phases, and varied attack patterns, beating down the player again and again.

Demon’s Crest managed to create deep immersion in the most unlikely genre, 2D action-adventure, turning what was an excellent game into a masterpiece.

Fantasy is a staple genre of video games, and lends itself particularly well to the medium. Rather than focusing so heavily on story, which either suck or are still inferior to a generic 1970’s paperback fantasy title, designers should focus on an element unique to games. Namely, the possibility of immersing the player through a combination of visuals, music, and the mechanics themselves.

Interesting and insightful. And not just for games. I wonder if this is why things like *Star Wars: Mary Sue Awakens* have not bombed completely.

Modern audiences don’t watch for the story. To them, a movie is a videogame for couch potatoes. Immersion is far more important than story. And immersion Hollywood can do, and do well.

Story in games is mostly useful just giving the player a sense of context. It’s important to remember that games work best when the player feels like he’s creating his own story.

One game I enjoyed a while back is Dark Messiah of Might and Magic. Fantastic first-person melee combat and some really neat magical tricks such as casting a sheet of ice on a ledge and watching charging orcs go sliding off into the abyss like Wile E. Coyote. The story was lousy, though. I remember being thrown out of the game because it sometimes made assumptions about how you/your character felt about developments in the story even though I felt nothing of the sort.