“It is a wild, savage, bitter story, I repeat, for no story of the Legion deals with life in a Boston drawing-room. Quaintly enough, this story has to do with a glass eye. And a live eye, too. You know that grim saying from the Bible: ‘An eye for an eye’? But yes. This is the story of an eye for an eye. And a grim little story it is.” – Thibault Corday

“It is a wild, savage, bitter story, I repeat, for no story of the Legion deals with life in a Boston drawing-room. Quaintly enough, this story has to do with a glass eye. And a live eye, too. You know that grim saying from the Bible: ‘An eye for an eye’? But yes. This is the story of an eye for an eye. And a grim little story it is.” – Thibault Corday

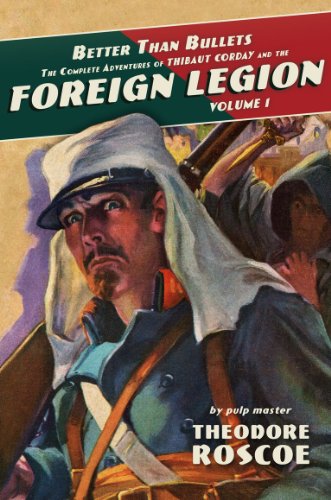

In “An Eye for an Eye”, by Theodore Roscoe, we return once more to the French Foreign Legion and the soldiers’ tales of Thibault Corday, the cinnamon-bearded retired legionnaire holding court in the cafes of Algiers. But where his introductory tale, “Better than Bullets”, was one of the humorous and sanitized tales every veteran keeps for the children, “An Eye for an Eye” is a far darker tale of betrayal and wrath. Corday spins this tale to vex a particular loathsome American, who boasts of a fortune made from glass eyes. And, as always, great troubles come from the smallest of provocations:

“When two boys love the same girl there is apt to be plenty of trouble. Especially if they already hate each other, as with the case with those two young cadets at St. Cyr.”

Corday recalls, as though from the front row of the audience, the crossing of swords between two cousins, Hyacinth and a promising cadet nicknamed Carrot (for his red hair). Jealousy provoked Hyacinth to strike at Carrot, and a beautiful and vain girl was just the excuse. The scoundrel left Carrot on the dueling field, leaving the once-promising cadet without an eye and with only the wrathful oath of taking an eye for an eye as company. Carrot would spend two decades training for and hunting down Hyacinth, with the cousins’ paths finally crossing in Dahomey, a dark and haunted land perfect for settling wrathful deeds.

In Corday, Roscoe captures perfectly the voice of a veteran and a veteran storyteller. Corday is a master entertainer, able to keep rapt audiences at the café–and those reading–with nothing but the spoken word. Word choice, rhythm, cadence–all the tricks of a master orator, captured neatly on the page. You can almost hear the old soldier’s laughter in each paragraph. It has been a vexing temptation to quote more from the old soldier than I already have. And it is my hope to one day find these stories matched in audiobook to the proper performer to give Corday’s words the life they deserve. Say, what is John Ringo up to, these days?

But what stands out the most in this tale of revenge is that Roscoe has created a naturalistic weird tale, full of exotica, dread, and uncanny occurrence. He just provides a convincing natural explanation for the events. Corday is known to embellish his stories–as is common for a tableside war story–he just never stretches credulity by bringing in the supernatural. The normal passions of men are dark and mysterious enough to provide the backdrop to this cautionary tale. Even the twist at the end, where we find out just how close the cinnamon-bearded veteran was to the clashes between dour Hyacinth and fiery Carrot, falls perfectly into the traditions of the Weird. And it is in this vein that many of Corday’s later tales follow.

The world might be plenty strange enough for Corday, but his tales are some of the most approachable of the adventure pulps, even now, where desert sands invoke Black Hawk Down instead of Lawerence of Arabia. Expect to see more about the old legionnaire, soon.

“Expect to see more about the old legionnaire, soon.”

Good news! Every time you post something on Corday/Roscoe, I get that much closer to buying this.

I never knew that Roscoe wrote fiction about the French Foreign Legion; I’m more familiar with his histories of the US Submarine and Destroyer services. How do his stories stack up against P.C.Wren?

I like a good yarn of the Legion and a naturalistic weird tale that takes the reader to the jungles of Benin rather than the deserts of the Sahara or Mexico sounds interesting.