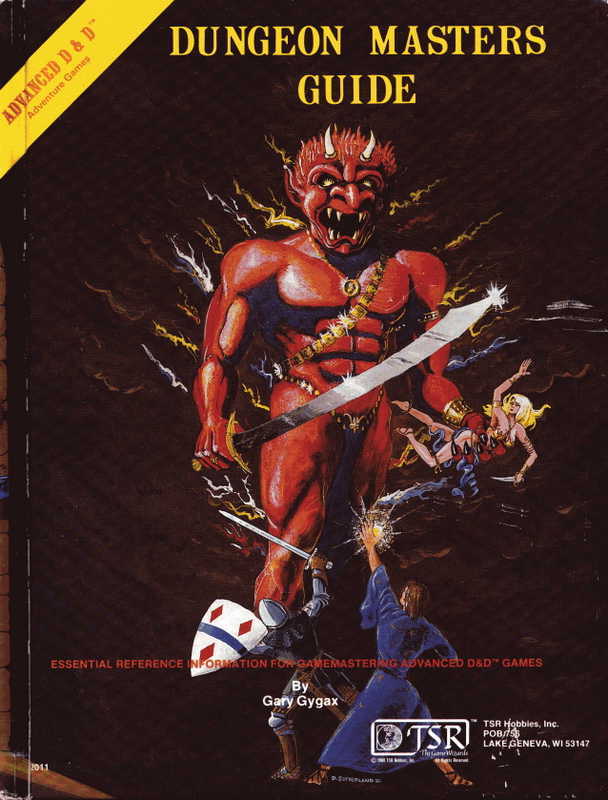

When Gary Gygax penned the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, the world was very different. The fantasy role-playing hobby was an entirely different beast than it is today, for one thing. But even the term “fantasy” would have had an entirely different connotation. While it’s possible to dive into the old guide, take a random rules element, and then trace both its origins and ultimate evolutions, I also find it enjoyable to go back and read Gygax’s prose just to get a feel for the kind of place he was writing from and the kind of audience he assumed he was writing to.

When Gary Gygax penned the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, the world was very different. The fantasy role-playing hobby was an entirely different beast than it is today, for one thing. But even the term “fantasy” would have had an entirely different connotation. While it’s possible to dive into the old guide, take a random rules element, and then trace both its origins and ultimate evolutions, I also find it enjoyable to go back and read Gygax’s prose just to get a feel for the kind of place he was writing from and the kind of audience he assumed he was writing to.

The section on “The Monster as Player Character” is particularly good for that:

On occasion one player or another will evidence a strong desire to operate as a monster, conceiving a playable character as a strong demon, a devil, a dragon, or one of the most powerful sort of undead creatures. This is done principally because the player sees the desired monster character as superior to his or her peers and likely to provide a dominant role for him or her in the campaign. A moment of reflection will bring them to the unalterable conclusion that the game is heavily weighted towards mankind.

I have to say that I have never really faced this problem. When I run classic style Dungeons & Dragons, I have to say… I have never had anyone ask to play an off the wall character concept. You find countless custom character classes in old magazines, in supplements, variants, and on gaming blogs. What you don’t find is players taking it for granted that the rules elements can be extended and altered and developed in direct response to whatever they want to play. Sure, they expect the Dungeon Master to fudge die rolls in order to keep the game on track so that everybody wins and nobody dies. But they do not expect to expect a long-running campaign to go off on its own direction.

But the kind of scene that provided the impetus for the introduction of (first) the cleric and then (later) the monk class…? The kind of environment that would cause J. Eric Holmes to leave the door open for a centaur, a lawful werebear, and a Japanese samurai fighting man class in the first D&D Basic Set…? It very rapidly ceased to exist in the years following the creation of these products.

ADVANCED D&D is unquestionably “humanocentric”, with demi-humans, semi-humans, and humanoids in various orbits around the sun of such as clerics, fighters, and magic-users — whether singly, in small groups, or in large companies. The ultra-powerful beings of other planes are more fearsome — the 3 D’s of demi-gods, demons, and devils are enough to strike fear into most characters, let along when the very gods themselves are brought into consideration. Yet there is a point where the well-equipped, high-level party of adventurers can challenge a demon prince, an arch-devil, or a demi-god. While there might well be some near or part humans with the group so doing, it is certain that the leaders will be human. In co-operation men bring ruin upon monsterdom, for they have no upper limits as to level or acquired power from spells or items.

Note that the original D&D trifecta of clerics, fighters, and magic-user is still the focus here. Note also the conception of the the default campaign that really would justify Deities and Demigods being the fourth core book. Gygax assumes that his planar cosmology is so integral to the game that it is a major reference point to be used in explaining why players can’t be monsters. And high level play is something that the players can actually progress to as part of their campaigns.

But note that he does not repudiate the power gaming mentality at all. No, his argument is that human player character monsters are the most dangerous beasts in the game!

The game features humankind for a reason. It is the most logical basis in an illogical game. From a design aspect it provides the sound groundwork. From a standpoint of creating the campaign milieu it provides the most readily usable assumptions. From a participation approach it is the only method, for all players are, after all is said and done, human, and it allows them the role with which most are most desirous and capable of identifying with. From all views then it is enough fantasy to assume a swords & sorcery cosmos, with impossible professions and make-believe magic. To adventure amongst the weird is fantasy enough without becoming that too!

The model of story-telling this game was engineered from is more in line with A. Merritt’s Ship of Ishtar, Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions, Philip Jose Farmer’s World of Tiers, Roger Zelazny’s Amber series, and De Camp and Pratt’s Harold Shea stories. It’s a premise that is ubiquitous in the pulps. You start with as mundane of a protagonist as possible so that the audience can learn about the weird and the impossible right along with him.

Why didn’t this aspect of the game remain part of the zeitgeist? I would argue that the edition of the game this paragraph appears in laid down the seeds of its destruction. The rejection of the original “3d6 six times in order” method of rolling attributes combined with not just a doubling or tripling of the available classes but also a range of races that could be combined with up to three of them at once…?! Even with the hard level restrictions from demi-humans, this sort of thing is an entirely different thing from what was implied by the original “little brown books.”

Consider also that each and every Dungeon Master worthy of that title is continually at work expanding his or her campaign milieu. The game is not merely a meaningless dungeon and an urban base around which is plopped the dreaded wilderness. Each of you must design a world, piece by piece, as if a jigsaw puzzle were being hand crafted, and each new section must fit perfectly the pattern of the other pieces. Faced with such a task all of us need all of the aid and assistance we can get. Without such help the sheer magnitude of the task would force most of us to throw up our hands in despair.

The assumption built in to the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game is that there will be no off-the-shelf campaign settings for Dungeon Masters to use. They have this elaborate cosmology being handed to them. They have this “zero to god-killer” arc baked into the rules. But there is still a massive amount of work that needs to be done. This is not a point where an entire line of products is envisioned, no ponderous box sets or sprawling “adventure paths.” No, this is instead where the burden of the referee is romanticized.

So now Gygax has three arguments against the use of “monster” characters. Humans are the better choice for people that genuinely want to power game, they are easier for players to role-play, and now… setting humanity as the default baseline makes it far easier for Dungeon Masters to develop their own campaign setting from scratch!

By having a basis to work from, and a well-developed body of work to draw upon, at least part of this task is handled for us. When history, folklore, myth, fable and fiction can be incorporated or used as reference for the campaign, the magnitude of the effort required is reduced by several degrees. Even actual sciences can be used – geography, chemistry, physics, and so forth. Alien viewpoints can be found, of course, but not in quantity (and often not in much quality either). Those works which do not feature mankind in a central role are uncommon. Those which do not deal with men at all are scarce indeed. To attempt to utilize any such bases as the central, let alone sole, theme for a campaign milieu is destined to be shallow, incomplete, and totally unsatisfying for all parties concerned unless the creator is a Renaissance Man and all-around universal genius with a decade or two to prepare the game and milieu. Even then, how can such an effort rival one which borrows from the talents of genius and imaginative thinking which come to us from literature?

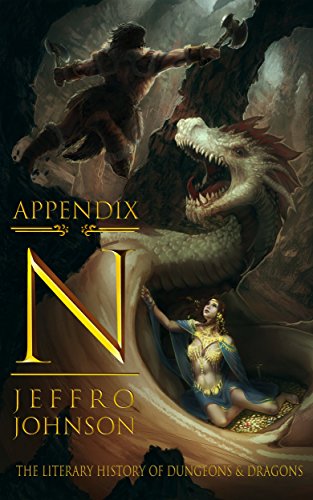

I’ve had a lot of people tell me that the Appendix N book list in the back of the Dungeon Masters Guide has nothing to do with the game. I’ve heard every dumb thing that can possibly said on the subject. That Gygax made it up in order to avoid lawsuits from the Tolkien estate. That he needed filler in an already overly large tome. That he wanted to sound more literate and clever than he really was. That he was merely suffering from an advanced sort of nostalgia for the sort of pulp stories he grew up with.

I’ve had a lot of people tell me that the Appendix N book list in the back of the Dungeon Masters Guide has nothing to do with the game. I’ve heard every dumb thing that can possibly said on the subject. That Gygax made it up in order to avoid lawsuits from the Tolkien estate. That he needed filler in an already overly large tome. That he wanted to sound more literate and clever than he really was. That he was merely suffering from an advanced sort of nostalgia for the sort of pulp stories he grew up with.

I don’t know why it is, but every blowhard and ignoramus on the internet seems to think that saying this stuff will make them sound really, really smart. But it doesn’t. Because Gary Gygax explained why he included Appendix N within the very rules that they are amended to. And the intent of the designer of AD&D was that Appendix N would be used to develop a humanocentric campaign setting that would give the best results in actual play while lessening the load on the already burdened Dungeon Master.

The weird elves, half-demons, fae-cat-girls you see in today’s bastardized and watered down variant of his system? Even in the late seventies Gygax knew that such an abomination would necessarily be “shallow, incomplete, and totally unsatisfying.”

“You start with as mundane of a protagonist as possible so that the audience can learn about the weird and the impossible right along with him. Why didn’t this aspect of the game remain part of the zeitgeist?”

Because D&D fantasy, through the game itself plus the many, many novels based around such concepts (such as Riftwar and most other “Tolkienesque” fantasy) became ubiquitous, well known, and the assumed default.

You cannot explore what everyone knows by heart. You can only explore the unknown.

Once you go from “here’s a character that’s mostly blank, with some basic pros and cons, so let’s find out what happens to him,” to “let’s roll up the character of your dreams so you can live vicariously through him,” I suppose it’s not too much more of a leap to, “but the character of my dreams is a demon king.”

That “3d6 in order” really was important, wasn’t it?

Man, I am super glad you found that first linked post; I’d read it once ages ago and had gotten into a discussion at one point about the multiple attacks against <1HD monsters, but then when I went back and looked, I could not find it in any of the stuff I had, because it was not in B/X and I think they may not have included it in OSRIC, and finding any specific rule in OD&D + Supplements is kind of a nightmare.

“Each of you must design a world, piece by piece, as if a jigsaw puzzle were being hand crafted, and each new section must fit perfectly the pattern of the other pieces.”

There is a lot to this between the lines; the implication is not that you need to come to the table with a completely finished and crafted setting to run your game in, but that you need to be able to make it “piece by piece”, responsive to your own needs and your players’ needs in a way that will “fit perfectly” with what you have already established.

It’s interesting that later in the 2000’s, Gygax had his own house rule for running OD&D:

Ability scores rolled as best 3 out of 4d6. Arrange scores to taste.

“2000’s”

“Ability scores rolled as best 3 out of 4d6. Arrange scores to taste.”

Pg 11 Method I AD&D DM’s guide 1978

-

Gary repeatedly stated that he did not use the AD&D rules for his own games, but rather stuck with the original D&D rules, plus his own house rulings, of course. I believe that Ostar was pointing out that even he may have eventually conceded to the ‘4d6 drop the lowest’ generation method at the behest of his players.