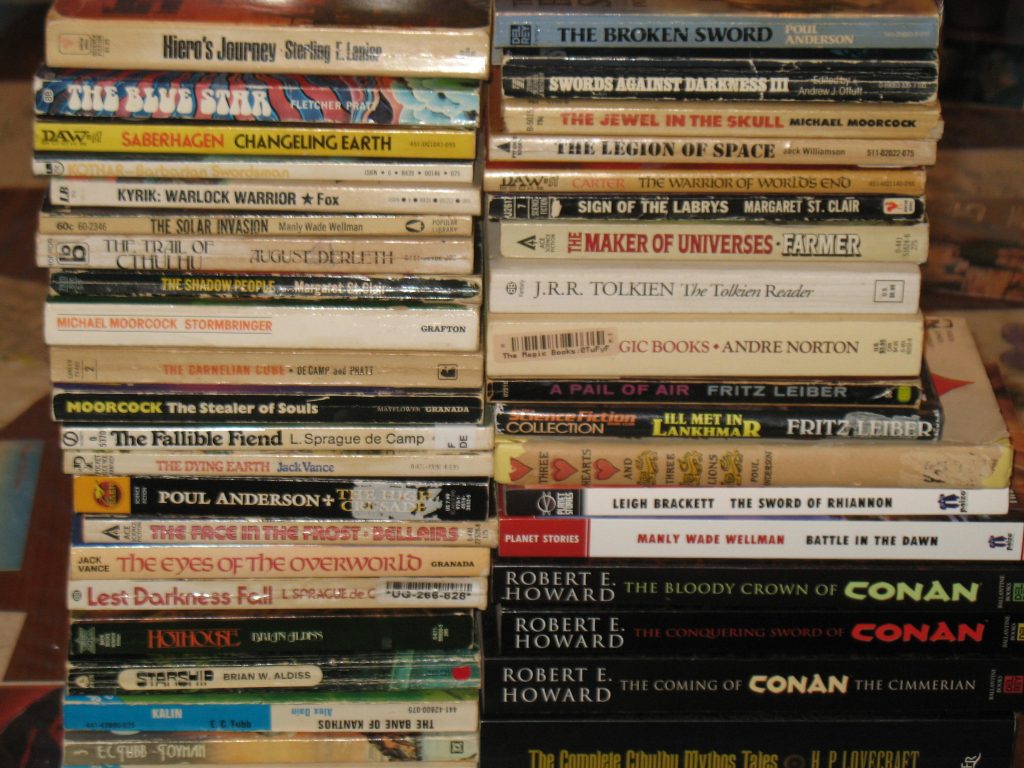

It’s difficult to find a stopping place with something like Appendix N. The forty-three installments of this series delve only into the books that Gary Gygax singled out in particular, and for the authors that he recommended their entire body of works, I only covered a single novel. Then there are the series that he highlighted– I stopped with those after the first volume when I sometimes wanted to put the entire project on hold to read them all. Finally, there are all the fantasy authors that wrote since the seventies that people think deserve a place on a list like this. People want to know if more recent authors measure up to these old classics, sure. But people really want to know which contemporaries of the Appendix N authors got snubbed by being excluded when they really deserved to be there.

It’s difficult to find a stopping place with something like Appendix N. The forty-three installments of this series delve only into the books that Gary Gygax singled out in particular, and for the authors that he recommended their entire body of works, I only covered a single novel. Then there are the series that he highlighted– I stopped with those after the first volume when I sometimes wanted to put the entire project on hold to read them all. Finally, there are all the fantasy authors that wrote since the seventies that people think deserve a place on a list like this. People want to know if more recent authors measure up to these old classics, sure. But people really want to know which contemporaries of the Appendix N authors got snubbed by being excluded when they really deserved to be there.

By far the most often suggested names that come up when people discuss the Appendix N list are C. L. Moore and Ursula K. Le Guin. And while I can see how Moore at least belongs on just about any list which includes both H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, I actually rather doubt that her omission is accidental. She wrote some of the greatest fantasy and science fiction stories ever written, no doubt– but her heroes lack the sort of “stamp” that would have most appealed to the co-designer of Dungeons & Dragons. Northwest Smith is at times a little too passive, a mere foil for some other overwhelmingly feminine character. Indeed, Moore could even write disembodied brains that positively exude femininity. While it’s positively astounding, it just isn’t consistent with the spirit of early D&D in the same way that Leiber, Vance, and Moorcock are.

That so many people insist on Le Guin’s Earthsea Trilogy perplexes me, though. It’s surprisingly dull in comparison to the other Appendix N books that Gygax mentions directly. Admittedly, the opening scene of the first novel where a novice spell-caster saves his village with the equivalent of a cantrip or two is pretty good. And the part where he defeats several dragons and even talks to one of them would be quite useful for anyone looking for inspiration for running their games. But the lack of connection to the real world that is so fundamental to the Appendix N books is missing here, making her work have more in common with the derivative works of the eighties really than anything in Appendix N. The way that the wizardly protagonist teams up with rather ordinary children in the second and third books is not just different from typical D&D stuff, it’s a little weird. And the defeating of Lovecraftian terrors with the power of friendship really isn’t how anyone handles adventures in a mythical underworld.

I really don’t think that many of us on the wrong side of the canon gap even know what we’re looking at when we see the list of Gygax’s inspirations. I think the fact that people are so quick to suggest that authors like Lord Dunsany be removed from it so that people like Le Guinn can replace them kind of miss the point. They’re simply not in tune with the times that produced it. This is a small thing, maybe… but in some sense it may be one of the most important thing that the Appendix N list preserves.

I say this because when I went and spoke to Ken St. Andre, someone that helped pioneer one of the earliest efforts in role-playing game design in response to and in competition with Gygax, I got a very different tone in his reactions than what I see in most Appendix N discussion. It almost sounded as if to him that L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter were figures to be held in reverence. Books like Roger Zelazny’s Jack of Shadows and Andre Norton’s Witchworld novels were spoken of as if the paperbacks had gotten as worn out as my copy of Fellowship of the Ring. And there… towering over all the other authors in both stature and influence was the man that dominated both Gygax’s and St. Andre’s concepts of fantasy and world building. No, it wasn’t J. R. R. Tolkien. It was Edgar Rice Burroughs. And the book series I needed to drop everything to go take a look at based on his advice…? It was Tarzan of the Apes, a hero that dates all the way back in 1912!

The thing I’d like most people to notice is the undiluted zeal of St. Andre’s discussions of classic science fiction and fantasy. And I tell you, even as the guy was confirming many suspicions I had and breaking down things that I’d been trying to articulate for a long while, even then I had trouble believing it. I mean, I’m the guy that’s been trying to explain to people for months that “Tolkienesque” fantasy really isn’t like Tolkien’s actual work. That “Lovecraftian” horror has very little to do with what Lovecraft actually wrote. And that the swords and sorcery genre that we think we know is a far cry from what it was that Robert E. Howard actually wrote. You’d think by now that I’d be able to take a guy at his word that a classic pulp fantasy novel really was undeniably awesome… but it’s not like that.

On some level, I must still think I know better. I still have this weird attitude permeating my assumptions about how reality actually works. The default setting of my brain is powerfully hidebound, even when it’s someone as cool as Ken St. Andre making the recommendation. That sounds crazy because you know I should know better. But I’m telling you that I do carry that attitude around me and it affects my choices of what I read and what I devote my time to. I know that for a fact because when Ken St. Andre was carrying on about the greatness of the old Tarzan stories, this smug and snarky reaction emerged unbidden from an odd corner of my brain: “eh, no way man.” Even after immersing myself in Appendix N for a year, I’m still a product of my own times as much as anyone, really.

But when I went and looked it up anyway, nearly every chapter had something in it that could surprise me. The savagery of it! The action! The oft omitted details that actually make sense of this character and which are absent from so many derivative works. The nuance that the many smear campaigns against the pulps have convinced me would not be there…! I was blown away. Repeatedly even.

I’m not alone in this. I am far from the only one. I know this because people like Stewart Gee write in to explain to me how it is for them:

My father, long ago, made mention in passing of his enjoyment in the original Tarzan and some of the stories that followed. I never fully understood the sentiment, or would have equated such appreciation with a potential kinship of spirit in other characters like Conan… until now.

He was from an older generation that saw two wars during its lifetime, and he harbored a deep love of both hunting and boxing. I find myself re-evaluating his tastes now, many years after his passing, and that is unsettling… but perhaps in this, he and I were more alike than I was willing to admit.

This estrangement between the generations… it isn’t normal. And it’s not just that people in the seventies would have read many of the same science fiction and fantasy authors that their parents and even grandparents did. The scope of things that fall within the black hole of the generation gap seems to be expanding almost exponentially now. Even things like Bugs Bunny and Tom & Jerry– I would have watched the same stuff that my big brother watched when I was a kid… and we were familiar with the same classic cartoons that out parents and grandparents would have watched. But that’s changed now. And it goes beyond these things just sort of quitely dropping off the radar for the moment. Millennials that will admit to never seeing them still “know” somehow that these things were racist or something and deserve to be erased. It might seem silly, maybe, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

When it was announced that the World Fantasy Award was replacing its iconic Lovecraft bust, Joyce Carol Oates declared that the literary canon is “saturated with racism, sexism, anti-semitism, anti-democracy… and lunacy.” Graciously she allows that “tossing it all out is no solution.” But why wouldn’t you toss it out…? If it really was as bad as people say, you probably would do just that. I mean really, why would people read the works of such terrible people…? They don’t. And if by some chance they do, the reaction can be almost physical sometimes, as this woman describes it:

I read a lot of Bradbury as a teen and thought his stories were wonderful. Rereading his stories now is actively painful to me. I’m a lot more able to pick up on those subtle cues, and less able to make excuses for them, that the author doesn’t really see his female characters as important, or real, or three dimensional, or people.

Are we really so advanced a civilization now that The Martian Chronicles necessarily should make us ill?

Older people steeped in the classics will dismiss that as an outlier, but it really is a sign of the times. This attitude certainly shows up in a great many of the reviews of old works of fantasy and science fiction that pepper the internet. It’s almost as if there is a barrier in these peoples’ minds. As soon as they get to something they been trained to think of as being “problematic”, they shut down. Very little in the way of any kind of analysis of the material can even be done, because calling out and reviling everything from Madonna/Whore complexes to “black and white morality” is the sort of thing that passes for deep or sophisticated thinking.

The retiring of Lovecraft’s bust from the World Fantasy Awards is therefore not so much reminiscent of statues of Stalin being pulled down in post-Soviet Russia. It’s more a reflection of the Berlin wall… going up. It used to be that reading centuries old books was almost universally considered to be a very good thing, to the point of being the very definition of an education. Now, looking into works that are merely decades old are increasingly beyond the pale. People with this attitude will even go so far as to object to having to read Ovid at university– and college administrators– far from standing up to this– seem instead to be on the lookout to accommodate this sort of thing.

In the not too distant past, though, the “dangerous visions” of the day could be enjoyed side by side with classic fiction by Lord Dunsany and A. Merritt. Professionals with highly divergent views on politics and religion could coexist within the pages of the same magazines. And people that were keen on challenging every imaginable taboo could get on within the same market where more traditional approaches to science fiction and fantasy were still practiced. People were free then in a way that’s hard to even imagine now. Political correctness and its legions of freelance thought police were only just beginning to gain a foothold, and remnants old ways and attitudes could be taken for granted.

The Appendix N list preserves therefore not just a list of books that are of especial interests to fans of classic Dungeons & Dragons. It’s also a snapshot of what fantasy fandom was into in the seventies. And don’t let anyone tell you different. While the list is not without its idiosyncrasies, it is nevertheless a representative sample of the authors that would have been translated into foreign languages when other countries finally got around to importing the fantasy and science fiction phenomenon for themselves.

For people looking to go beyond the three biggest names in fantasy fiction of the 20th century, it is a great start. Our science fiction and fantasy heritage is greater than we know, and far better than many would suspect. But this survey of works spanning the better part of six decade also reveal the surprising scope and rapidity of the changes within our culture. Even a brief survey such as this reveals much that is just barely conceivable to this generation. And though these works were primarily intended to entertain, they nevertheless preserve a vision of courage, determination, and undiluted heroism that we sorely need today.

Appendix N contains not just the story behind how familiar genres and games came to be. It also preserves a sense of who we were… and what we could yet become again if we chose to.

That is an excellent summary.

Jeffro,

I’ve really enjoyed the series! Thanks for putting it all together. It has increased my reading list quite a bit. I’ve wanted to check out Edgar Rice Burroughs for awhile. I think I’ll try to find Tarzan and see if my kids could read it.

-

I bought complete Howard, Burroughs and others formatted for Kindle for next to nothing. Tarzan was astonishing and John Carter but so were things like Howard’s Prester John and Solomon Kane. I had only read Conan as a “yoot”.

-

Project Gutenberg is a great source for many of ERB’s books, and free to boot. The site has many Public Domain and expired copyright works available for download. Libravox makes works available in audio book format for those who want to listen to these texts.

Outstanding series that I’m reading in a quasi-random order. Well done, Jeffro! Should be a book!

-

Is there some page listing all the appendix N posts? I just discovered the series and it seems like it would be a good read.

I hope Appendix N will be published as a book eventually — it’s been a valuable series. Any fantasy fan or writer who hasn’t read Burroughs, Merritt, Moore, Howard and all the rest of these — not to mention Bradbury! — is like a movie fan who’s never seen a black-&-white movie (much less a silent!).

I used to teach High School, ERB was required reading. The number of students who read Tarzan or John Carter and told me they didn’t know that they wrote books like this was astounding. The number who realized ERB’s Tarzan was not the Tarzan of TV and was a deep full character and the stories were far more thought provoking than vampire romance novels was astounding. But I got them before they young enough to not be molded into some politically correct ideotrom.

Methinks there may be an opportunity here.

Questions:

1. If the World Fantasy Award is renouncing the use of the HPL bust, how much would it cost to acquire all remaining unawarded copies of said busts, and, likewise, to offer to purchase the previously awarded busts (at cost, because really, who would want such an icky thing on their mantle and what better way to signal loyalty to the warren than divesting oneself of such a terrible icon)?

2. What would be involved in acquiring the rights to said busts for subsequent issue by the brand new (that I just made up) first annual, “International Fantasy Award” for best fantasy authors.

-

It’s too late for a FIRST annual International Fantasy Award. It was issues five times back in the 1950s. I know, that’s prehistory. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Fantasy_Award

-

Thanks. Sorry for not being more clear. I was being facetious. But, half-joking is also half serious. It still looks like an opportunity to construct a parallel, competing structure. Being the knuckle-dragging, mouth-breather in the room, I can’t be the first to notice this. Where they withdraw, we advance.

-

I’m sorry I’ve only just now been made aware of this excellent series (thanks John C. Wright)! As a die-hard Gygaxian, I’ve slowly worked through Appendix N myself over the last several years. We have to read those books for the same reason we still have to read the Iliad etc. Classics for a reason.

I guess I have a lot of posts to go back through on your site! Great work here.

Re. Earthsea:

I suspect that some of the dullness is attributable to the Taoist ethos with which Le Guin infused the trilogy. The hero (Sparrowhawk?) finds solutions to his obstacles by isolating himself from the cares of the world and placing himself in balance with his surroundings. One of only two or three scenes I recall clearly is from the climax of book three, where the antagonist is defeated by…earnest conversation which shows him how he has placed himself in opposition to the Way, and convinces him to return to it.

*shrug* I know little of Daoism, and don’t recall thr books well, so it’s entirely possible I’m talking out my 4th point of contact. If anyone here recalls Earthsea better than I, I’d be interested in hearing differing opinions.

-

I recall it being something like “Look, man, you’re dead.” “Fuck, you’re right!” ::crumbles to ash::

As much as I loved Tombs of Atuan, making the priestess a little girl was a subversion that I don’t even think LeGuin was happy about. You ended up with a protagonist who had very little agency and, because she was a little girl and Ged was celibate anyway, got unceremoniously dumped away from the plot as soon as the MacGuffin she was guarding got collected, because there was no reason for the series’ hero to be invested in her.

I feel like maybe LeGuin wanted to rectify this with Tehanu, but ‘old people learn to fall in love’ made for a hella boring fantasy novel.

I remember binge-downloading a bunch of older books from Project Gutenberg. Tarzan of the Apes was among them.

You’re right about that: It *is* an awesome book. Surprisingly so.

I read these books sometimes because I want a window into these times by authors who lived in them, or could remember them.