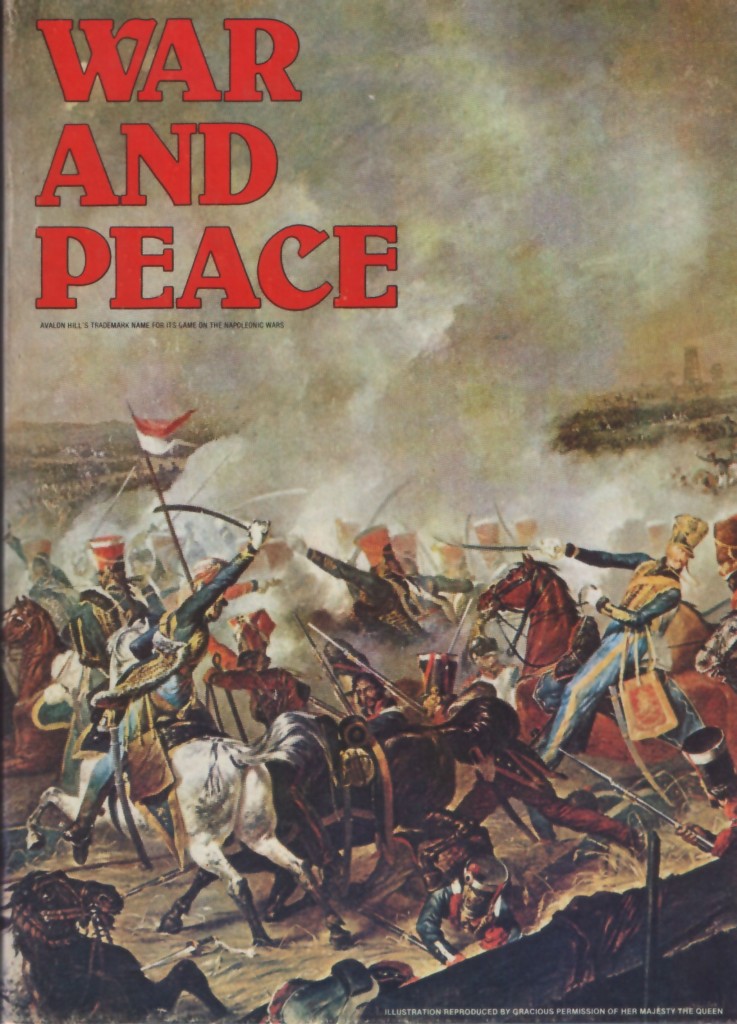

It turns out I had been losing in Malta much worse than I thought. My dad suggested I count my dead pile before going forward, and I found that I had already suffered enough airborn losses to prevent an Axis victory. Rather than replay Malta until one of us could figure out a winning strategy for the German/Italian player, we decided to move onto War and Peace, a strategic level game of the Napoleonic Wars.

It turns out I had been losing in Malta much worse than I thought. My dad suggested I count my dead pile before going forward, and I found that I had already suffered enough airborn losses to prevent an Axis victory. Rather than replay Malta until one of us could figure out a winning strategy for the German/Italian player, we decided to move onto War and Peace, a strategic level game of the Napoleonic Wars.

War and Peace is a game that perhaps seems more complicated than it actually is. The way mechanics are described in great, arduous and frequently redundant detail gives the impression of cumbersome resolutions during which more dice rolling takes place than playing. This is not the case, however, and I’m delighted to say that we made it through our first scenario in less time than it took to read the rules.

War and Peace offers the option to play either one of a number of scenarios reflecting pivotal battles and campaigns throughout Napoleon’s career or a “Grand Campaign” meant to encompass the entirety of the Napoleonic Wars. The game accommodates a large number of players (up to six) for those with enough friends, enough time and enough space to sprawl out the several boards and player aids. For those either suffering from limitations of the aforementioned or just curious to try the game out, the scenarios strip out economic and naval considerations, POWs, and most of the intricate Alliance system as well as one or two of the four boards.

In my magnanimity I chose to play as the Austrians for the Austerlitz scenario. We chose that battle because it was a quickie (5 turns), and without needing the Russia and Spain map leaves, we’d be able to fit the map and the charts on the table with room to spare. In the end, things went about as historically accurate as one might expect; Napoleon overwhelms Mack and Ferdinand at Ulm, smashed his way through Prague and takes Vienna just as the Russians are beginning to arrive too late. I was not playing too hard to win it, else I would’ve sent Archduke Charles back to stall the French advance rather than have him take Mantua, Milan and ultimately Lyon.

Without worrying much about the political and economic mechanics from the 1805-1815 “Grand Campaign” game, War and Peace is an incredibly simple game. Attrition is figured by a single die-roll applied to your hexes by a stacking value. Cavalry move 4 while Infantry move 3 (the latter only with a leader). Force marches are adjudicated by a simple table. Combat odds are only ever figured at 1-1, 3-2, and 2-1+, so the results table is kept small.

There is a bit of nuance to the combat by way of morale, leadership and tactics. Units have varying morale factors ranging from 3 to 0, determined by nationality, troop type or special rules. For instance, the Russian Patriotism bonus gives all Russians +1 on Russian soil. Stacks use the morale value of the majority of force in a hex; hence troops with 0 morale (peasant militias and Cossacks, for instance) will break and run if there are ever more of them than unbroken regulars). Leaders can also contribute their leadership value to the battle as a modifier. The difference between the two forces’ combined morale and leadership is either added or subtracted from the die roll. War and Peace uses tactics modifiers similar to 1776; here, however, flank-right/flank-left and refuse-left/refuse-right have been combined and replaced with “envelop flank” and “refuse flank”, and the game uses chits rather than cards. The tactics, while fun and interesting (there’s really no reason not to use them), had a fairly small impact when taken into account alongside morale/leadership modifiers.

Combat is played out in rounds; the description in the rules makes these combats sound like they’d take much longer or have more twists and turns than they did in practice. Typically, the larger force, unless hit with truly crippling negative modifiers, will wear away the smaller force until it’s eliminated; it’s mostly a question of cost to the attacker. Adjacent armies having the ability to try to jump in after the initial round of combat seems like a neat idea, and in other scenarios would probably have a lot greater effect on the ebb and flow of battles, but did not really come into play much here, as most of my Austrian forces were spread out, outnumbered and outclassed. Sieges were another mechanical option that did not have much relevance in the Austerlitz scenario; Napoleon has 5 turns to steamroll the Austrians from Ulm to Vienna and lengthy sieges just aren’t on the table for him. In a much longer game, sieges and treatment of cities as something like a ‘hex within a hex’ would probably have more relevance.

Pieces are a bit larger than the hexes, so you may actually consider clipping your counters even though there are several hundred of them; this is the first game I’ve played where I’ve said “Man, this really needs clipped counters!” Fortunately, big piles are almost never out on the board; the handy-dandy player aid with the combat, attrition and force march tables also has boxes for each Commander piece where troops under their command can be placed.

After Malta, the relative simplicity of War and Peace was a breath of fresh air. Again, I can’t attest to “Grand Campaign” game, but the scenarios, if they’re anything like Austerlitz, are quick to set up and easy to play. The rules are less daunting than they come across as in the manual. At least one player should be an experienced war gamer to help parse some of the chunky language, but War and Peace provides a decent opportunity for several players new to war gaming to gather around the table. If played as a family affair, it may prove a perfect opportunity for the kiddos to team up against dad in an all-out effort by the rest of Europe to stop Napoleon’s designs for world domination.

Wikipedia has a surprisingly detailed entry on War in Peace.

-Alex

Please give us your valuable comment