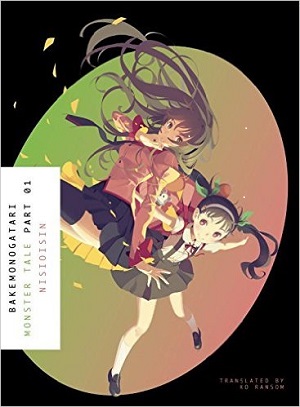

If you’ve read my review of NISIOISIN’s Bakemonogatari Part 01, you’ll know that I am not a fan of the story “Mayoi Snail.” Not only do I find it a slow story hobbled by Koyomi’s need to be clever and the long wait for Hitagi to return with the solution to Mayoi’s mystery, I have long grown tired of the anime tropes that pop up, specifically lolicon, skinship, and pain paying for wandering hands. The pulp-influenced mystery behind “Hitagi Crab” is more to my tastes. However, some of my criticism of “Mayoi Snail” is because I didn’t completely understand the story.

If you’ve read my review of NISIOISIN’s Bakemonogatari Part 01, you’ll know that I am not a fan of the story “Mayoi Snail.” Not only do I find it a slow story hobbled by Koyomi’s need to be clever and the long wait for Hitagi to return with the solution to Mayoi’s mystery, I have long grown tired of the anime tropes that pop up, specifically lolicon, skinship, and pain paying for wandering hands. The pulp-influenced mystery behind “Hitagi Crab” is more to my tastes. However, some of my criticism of “Mayoi Snail” is because I didn’t completely understand the story.

This is no fault of translator Ko Ransom, I found the translation to be excellent, delightfully lacking in the fetishizing of the Japanese language often imposed on works by the expectations of anime and manga fans. Furthermore, there wasn’t the funny word order that often comes from literal and direct translation of Japanese grammar, as I have seen time and time again in fansubs and fan translations of light novels such as A Certain Magical Index and The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya. Rather, as a foreign reader, I did not recognize the Chinese-influenced structure of the story, known in Japanese as Kishotenketsu.

Originally developed in Chinese four-line poetry, the kishotenketsu form was adopted by narrative story and even formal academic essay. For those familiar with Japanese visual culture, the 4-koma, or four panel comic strip, represents the most familiar application of kishotenketsu structure. Whether argument, poem, story, or comic strip, the work is divided up into four parts:

- The introduction: The characters, setting, and situation are introduced.

- The development: Themes and events in the introduction are built upon and developed in more depth.

- The twist: An unexpected event illuminates everything that happened before in a new light.

- The conclusion: Not only does this wrap up the dilemma of the story, it explores the consequences of the twist.

The first act is self explanatory. It’s where we’re introduced to the story and we get to know the characters taking part and the world they live in.

Similarly, the second act also doesn’t require much explanation. This is where we get to know the characters a little better. We learn about their relation to each other and their place in the world. This is where we develop an emotional connection to the characters.

The third act however, the twist, is where things get a bit complicated. I’ve seen this act referred to as complication, and while I don’t think that’s technically correct, I feel it’s a better name. Calling it a twist brings with it associations to plot-twists as we know them from more traditional western narratives.

This isn’t necessarily the case here. It can be, but it doesn’t have to. However, it’s often something unexpected, and usually unrelated to what’s happened in the first two acts.

Finally, the fourth act is about the impact of the third act on the first two acts. This is why I like the term reconciliation. The third act will affect the situation presented in the first and second act, and in the fourth act the state of the world in first and second act is reconciled with the events of the the third.You can see how cultural differences between East and West come through in each culture’s preferred storytelling methods.

Kishōtenketsu emphasizes developing a cast of characters over focusing on an individual protagonist. The Eastern approach is also more concerned with reconciling the story’s events to the status quo ante.

As Brian says, and much to many a post-modernist critic’s disgust, this doesn’t mean that the story does not have conflict. Just watch Shaw Brothers kung-fu films such as Come Drink With Me or The 36th Chamber of Shaolin to see conflict in kishotenketsu. But the conflict is not built into the structure of the story like in Western works. Instead, it becomes part of the milieu for episodic adventures. And just as a three-act writer will string together multiple try-fail cycles into a story, many light novels and Chinese films combine multiple kishotenketsu episodes together into one story. It takes clever plotting to do this without feeling aimless or disconnecting from lore, as can be seen in the faults of several xian’xia tales and light novels. Kishotenketsu episodes can also vary wildly in tone and mood as a result.

The strengths and the weaknesses together are key components to the style of fiction I call Blue Slime Fantasy, which uses Dragon Quest and MMOs for inspiration.

Kishotenketsu can be applied to “Mayoi Snail” as follows:

- Introduction: Koyomi and Hitagi are in a large park, where they see a lost girl, Mayoi.

- Development: Koyomi tries to help Mayoi find her home, but no matter how long or how far they go, they never find it. Hitagi is worried about an aberration affecting Mayoi and leaves for help. Tsubasa appears, scolding both Koyomi and Mayoi.

- Twist: Hitagi returns, telling Koyomi that not only is Mayoi the aberration, she had not once been able to see Mayoi. Only those who are unhappy can see a Lost Snail aberration.

- Conclusion: Hitagi and Koyomi are able to return Mayoi to her house, ending the effect of the aberration on the ghost girl. Koyomi comes face to face with some of the issues in his life – and the fact that Tsubasa’s unresolved unhappiness is a ticking time bomb.

With this greater understanding of technique, “Mayoi Snail” does rise a notch or two in my esteem, but not enough to displace “Hitagi Crab” as my favorite Bakemonogatari short story.

Miyazaki uses this structure to frequent and great effect, to the point that people often marvel at how “plotless” some of his best films are. He is often accused of being loose with structure.

This is untrue. In fact almost all of Miyazaki’s stories are very tightly structured and plotted, just not in ways we might understand.

Spirited Away is often called a series of random and unconnected events, but this is wrong. The events are, however, structured via kishoutenketsu, not the typical western narrative structure, and so folks like us watch it and think “Huh, how random” when it is in fact anything but.

Your Name works similarly. I remember the gentleman over at Script Shadow saying Your Name was one of the worst plotted films he had ever seen, and even some good reviews I saw – like Digibro, who should know better – point out that relatively little actually happens in it.

Which misses the point. Your Name is a kishoutenketsu. The structure inherently has much less conflict, and if you don’t know the structure things would look haphazard and random. Regardless, the structure DOES exist.