Between Sherlock Holmes and Marlowe: Nero Wolfe

Saturday , 25, November 2017 Authors, Before the Big Three, Fiction 13 Comments It’s easy to forget nowadays, given the legion of predictable, played-out, repetitive, and boring works, but the mystery genre is relatively young. The earliest notable entries were several Poe short stories featuring C. Auguste Dupin (1841-1844), Collins’ The Moonstone (1868), and Dickens’ unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). The Dupin stories were the earliest and most influential, but simplistic even by the late 1800s. Meanwhile, The Moonstone is an extraordinary masterpiece, one of my favorite works of the entire 19th century, but it was a stand-alone novel without a focus on the main detective and written in epistolary form from multiple perspectives. Thus, while rightly celebrated, it didn’t have much impact on future authors within the genre.

It’s easy to forget nowadays, given the legion of predictable, played-out, repetitive, and boring works, but the mystery genre is relatively young. The earliest notable entries were several Poe short stories featuring C. Auguste Dupin (1841-1844), Collins’ The Moonstone (1868), and Dickens’ unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). The Dupin stories were the earliest and most influential, but simplistic even by the late 1800s. Meanwhile, The Moonstone is an extraordinary masterpiece, one of my favorite works of the entire 19th century, but it was a stand-alone novel without a focus on the main detective and written in epistolary form from multiple perspectives. Thus, while rightly celebrated, it didn’t have much impact on future authors within the genre.

It wasn’t until the late 1800s and early 1900s that the mystery genre became especially popular, initially in England. Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes is the firth sleuth that comes to mind, and his adventures are still among the very best of the genre. I also especially like Chesterton’s Father Brown stories that began in 1910. In addition to being clever mysteries, they bear Chesterton’s dark, insane style, which very few mysteries since have employed to such great effect. Of course, not all that was popular then was good. I still don’t understand how Agatha Christie’s books, which have sold more than those by any other author in human history, attained such success. They are insultingly simple, with deductions that require a half-step of reasoning, or else a lazy metaphysical explanation. The stories themselves are the worst kind of English provincial bore, giving me bad flashbacks to novels of manners written during the Victorian era with hundreds of pages of nothing.

A main element throughout all these stories, good and bad, is a great detective using his (or her, in Miss Marple’s case) intellect to figure out the case. While there is occasionally a search for clues, the breakthrough is usually accomplished in the comfort of the detective’s study. The “action” is then relegated to the detective explaining how he solved the case, and a possible further explanation from the culprit. There is typically little drama associated with the arrest.

A few decades later, pulp detective stories would really take off in the United States. Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, Raymond Chandler’s Phillip Marlowe and Nick and Nora Charles, and a number of fine novels by James M. Cain. Unlike the English works, these were not about quiet intellectuals, but about investigators who got their hands dirty. This would mean scrounging around for clues in seedy neighborhoods, dealing with low-level hoods, and fights. Furthermore, there was often as much ingenuity and adventure in apprehending the criminal as solving the case!

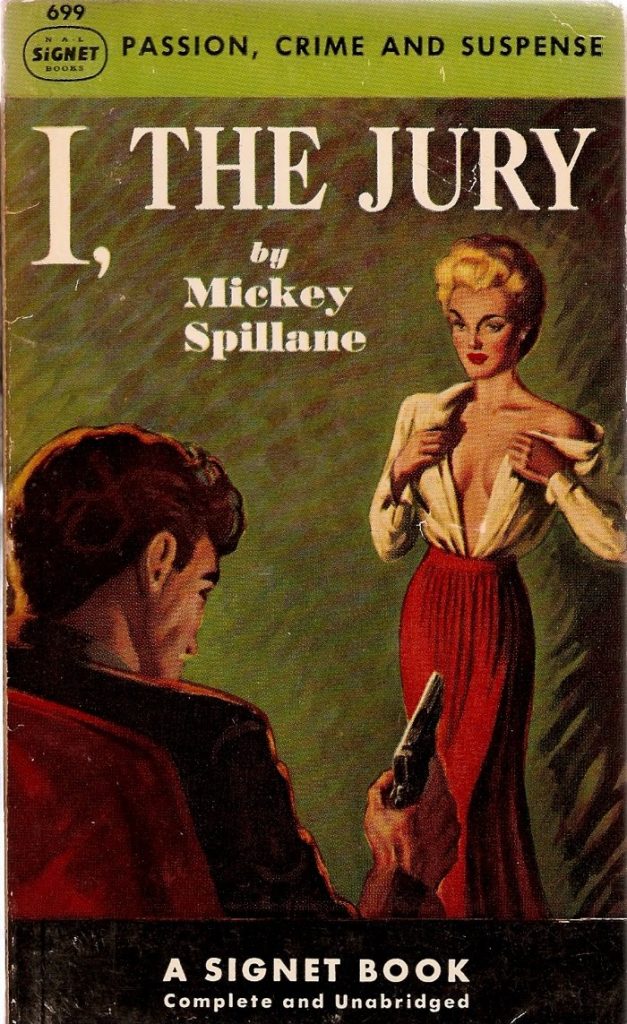

Spillane’s Mike Hammer covers had a simple, effective formula; a gun and a beautiful woman in some state of undress.

I would also be remiss not to note that these American stories had some phenomenal movie adaptations that their English cousins lacked, whether it’s the classic Thin Man movies starring William Powell and Myrna Loy, the outstanding Double Indemnity film directed by Billy Wilder (with the original story written by Cain, but the film script adapted by Chandler!), or the Maltese Falcon with Humphrey Bogart.

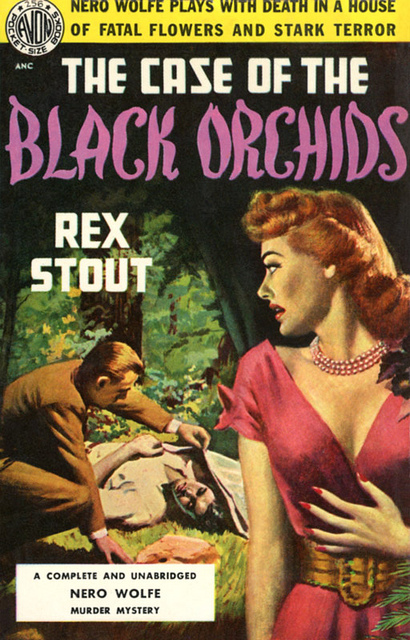

An interesting attempt in 1934, only 5 years after Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, and a year after Chandler started writing, was the publication of Rex Stout’s Fer-de-Lance, the first mystery starring Nero Wolfe. In many ways, it sought to bridge the gap between English and American detective fiction. On the one hand, you had Wolfe, an obese shut-in with a love of plants and large dinners. He is very much the eccentric genius in the mold of a Sherlock Holmes. Stout even tried to make him surpass the original, making him rude and difficult to the point where the idea of anyone working for him is sheer lunacy.

On the other hand, the American detective story is present in Archie Goodwin, Wolfe’s agent on the street. Goodwin gathers clues, interviews witnesses, gains the confidence of the ladies, and is the main narrator of the books. He regularly mouths off and gets into fights with cops and criminals alike, replete with 1930’s slang.

Thus, this is an attempted synthesis of the two distinct styles of mysteries. The pulp with its earlier English antecedent. is Stout’s work successful in this endeavor?

Honestly…no.

Although competently written, the book is frequently plodding and utterly unexceptional.

While Stout combined the two approaches, each one is strictly worse than its inspiration. Wolfe is far less interesting and entertaining than a Sherlock Holmes or Father Brown, and Goodwin is a pale imitation of a Spade or Marlowe. The deductions are far simpler and the fights and chases nowhere near as thrilling as their respective inspirations. I often think that Stout modeling his work so closely after other ones hurt him. Wolfe’s antics made me think of what a bad parody he is of Sherlock Holmes, and Goodwin’s insults call to mind how much cooler and more tense Chandler’s protagonists are.

Still, it was an interesting experiment, and in its failure, (from a quality perspective; it sold well enough, as any half-decent mystery work back then seemed to) exposed the demands of both the British and American approaches.

Rex Stout was always really good at atmosphere. So was Agatha Christie. If you are in the mood for a timelessly English atmosphere, you like Christie. If it feels timeless like a broke watch, you hate Christie. If either writer’s deductions are insultingly simple, you should be writing your own detective stories.

If you found Christie’s plots anything but exceedingly clever on average you are a smarter man than I.

Christie figured out exactly what the expected “rules of engagement” were for murder mystery readers. And then she systematically violated those rules in her stories.

Whodunnit? Can’t be the narrator, right? Or one of the victims? Or all of the suspects? Or the detective? She did all of those. Once you realize that she’s not so much writing novels as constructing puzzles, they make more sense. But as stories they’re nonsensical.

I agree with you about Nero Wolfe. Never saw the appeal.

You might want to read more than one of Stout’s books before passing judgement on the Nero Wolfe series as a whole.

@What would you recommend?-

Jacques Barzun, A Catalogue of Crime. Read the foreword and look at the reviews of books you’ve read, so you know where the Catalogue is coming from. Hint: Mickey Spillane was not writing puzzle stories.

Read what you like. If Nero Wolfe isn’t to your taste, you’re not alone. Those stories have a very definite New York flavor to them, and I know people who find that off-putting. I’ve read most of the Nero Wolfe stories and I found any of the following to be superior to Fer-de-Lance. In no particular order:

The Mother Hunt, The Doorbell Rang

The Black Mountain, The Golden Spiders

Gambit, The League of Frightened Men

Too Many Cooks, The Silent Speaker

If Death Ever Slept

Some of his short stories are quite good too.

The Nero Wolfe books are like the Travis McGee books in one respect: I’ve read them all, but for the life of me, I couldn’t tell you what the first one (The Deep Blue Goodbye) in the series was about. I much more enjoyed the books in the middle of the series and the final one (The Lonely Silver Rain).

Your tastes will vary.

Vlad

I agree with you that I son’t like either Poiroit or Miss Marple. I prefer Tommy and Tuppence. As for Nero, i appreciate them and better than some of the contemporary dectective fiction.

As for British fiction,i’ve always suspect a class thing: most were written by professionals i.e. doctor etc so there was a minimization of getting your hands dirty.

Americans were more working class so getting hand dirty is the job.