Bro, Do You Even Read: The Movie

Friday , 24, February 2017 Appendix N, Before the Big Three, Pulp Revolution 64 Comments There’s bit of a push right now for some of us to moderate our tone. The fear is that we’re going drive away potential readers… at the very time when this blog is having it’s best month ever in terms of traffic. The concern is that we might lose our rep for being builders… at the very moment when G+ is implementing throttling technology to push links to Castalia House blog away from outsiders that have never read anything like what we do here. The accusation is that we are creating a revisionist history… by people that are unable or unwilling to discuss the things we delve into in public.

There’s bit of a push right now for some of us to moderate our tone. The fear is that we’re going drive away potential readers… at the very time when this blog is having it’s best month ever in terms of traffic. The concern is that we might lose our rep for being builders… at the very moment when G+ is implementing throttling technology to push links to Castalia House blog away from outsiders that have never read anything like what we do here. The accusation is that we are creating a revisionist history… by people that are unable or unwilling to discuss the things we delve into in public.

You have no idea how this affects us, really. I mean… it just registers as pleas for mercy. The really rabid pulp revolutionary types…? It makes them feel like Confederate troops under Stonewall Jackson at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Seriously, if you want to moderate us, the only way you’re going to manage that is by writing reviews of the things you like. Or coming up with your own critical frame. Or doing the sort of tedious research that guys like Nathan Housley seem to dive into for fun. I mean you act like we’re not the people that hosted H. P.’s piece on Have Spacesuit Will Travel or Misha Burnett’s Appendix X series. And you know Castalia House publishes a whole line of Heinleinesque juveniles, right…?

Anyway, given the number of critics we have that are rightly afraid to engage us in conversation much less debate, I’m going to take a look at the best competing frame on the market from before the time when Castalia House took off. It’s the one by Eric S. Raymond… and if you don’t know who that is, well… suffice it to say the man is a giant in the computer programming world. He’s also one of those people that seems to actually think before he writes and that is open to changing his opinion in response to new information. A very cool guy. And I say all that not just because I’m about to lay into him here. But yeah… I’m about to lay into him. And the reason I’m doing it is because of the number of people that have loudly and disingenuously claimed that the stuff I write about isn’t obscure. Au contraire… just look at the conversation and how much it’s changed.

So here we go!

The history of modern SF is one of five attempted revolutions — one success and four enriching failures. I’m going to offer you a look at them from an unusual angle, a political one. This turns out to be useful perspective because more of the history of SF than one might expect is intertwined with political questions, and SF had an important role in giving birth to at least one distinct political ideology that is alive and important today.

The first and greatest of the revolutions came out of the minds of John Wood Campbell and Robert Heinlein, the editor and the author who invented modern science fiction. The pivotal year was 1937, when John Campbell took over the editorship of Astounding Science Fiction. He published Robert Heinlein’s first story a little over a year later.

A big fat nope here. The Pulp Revolution predates that Campbellian one. The publication of A Princess of Mars changed everything. Y0u cannot underestimate the extent to which Edgar Rice Burroughs shook things up. Ray Bradbury called him the most influential author in the entire history of the world. And Ray Bradbury knew what the hell he was talking about. Everybody else…? They deal with the inconvenient fact of this man’s career by redefining their terms in order to write him out of history. It’s tacky to say the least.

Pre-Campbellian science fiction had bubbled up from the American pulp magazines of the 1910s and 1920s, inspired by pioneers like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells and promoted by the indefatigable Hugo Gernsback (who had a better claim than anyone else to have invented the genre as a genre, and consequently got SF’s equivalent of the Oscar named after him). Early “scientifiction” mostly recycled an endless series of cardboard cliches: mad scientists, lost races, menacing bug-eyed monsters, coruscating death rays, and screaming blondes in brass underwear. With a very few exceptions (like E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark of Space and sequels) the stuff was teeth-jarringly bad; unless you have a specialist interest in the history of the genre I don’t recommend seeking it out.

You want to know why nobody paid attention to the pulps before Castalia House blog got rolling…? Because of outright lies like this.

You can tell Raymond has no idea of what he’s talking about when he deploys the phrase “screaming blondes”. He’s taking a stereotype from nineteen-fifties B-movies and then assuming he can extrapolate backwards from it. In his ignorance, he superimposes his assumptions on a diverse range of authors that he knows nothing about. People in the Weird Tales scene of course comprehend the fact that H. P. Lovecraft wrote science fiction in this time period. They thought I was stupid when I acted like this was some kind of revelation. But people like Eric S. Raymond have no idea.

John Campbell had been one of the leading writers of space opera from 1930, second only to E.E. “Doc” Smith in inventiveness. When he took over Astounding, he did so with a vision: one that demanded higher standards of both scientific plausibility and story-crafting skill than the field had ever seen before. He discovered and trained a group of young writers who would dominate the field for most of the next fifty years. Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson, and Hal Clement were among them.

Heinlein was the first of Campbell’s discoveries and, in the end, the greatest. It was Heinlein who introduced into SF the technique of description by indirection — the art of describing his future worlds not through lumps of exposition but by presenting it through the eyes of his characters, subtly leading the reader to fill in by deduction large swathes of background that a lesser author would have drawn in detail.

(Many accounts have it that Heinlein invented SFnal exposition by indirection, but credit for that innovation may be due to none other than Rudyard Kipling, whose 1912 story With The Night Mail anticipated the style and expository mechanics of Campbellian hard science fiction fourteen years before Hugo Gernsback’s invention of the “scientifiction” genre and twenty-seven years before Heinlein’s first publication. Heinlein professed high regard for Kipling all his life and included tributes to Kipling in several of his works; it is possible, even probable, that he saw himself as Kipling’s literary successor.)

This is just flat wrong. Not the part about the coup and the domination of the field. Yeah, that happened. In fact… you’re watching it happen again right now.

This rest is just pure narrative. The authors in Campbell’s stable were collectively inferior to the ones they displaced. The only way that you can push this line is by redefining science fiction such that the good stuff didn’t count anymore. For most people, this is all they’ve ever heard– so when they sit down to read the old pulp science fiction from the twenties and thirties, they are shocked by how much science is in them and how thrilling the stories are.

There’s no nice way to put it: you’ve been lied to.

From World War II into the 1950s Campbell’s writers — many working scientists and engineers who knew leading-edge technology from the inside — created the Golden Age of science fiction. Other SF pulpzines competing with Astounding raised their standards and new ones were founded. The field took the form of an extended conversation, a kind of proto-futurology worked out through stories that often implicitly commented on each other.

While space operas and easy adventure stories continued to be written, the center of the Campbellian revolution was “hard SF”, a form that made particularly stringent demands on both author and reader. Hard SF demanded that the science be consistent both internally and with known science about the real world, permitting only a bare minimum of McGuffins like faster-than-light star drives. Hard SF stories could be, and were, mercilessly slammed because the author had calculated an orbit or gotten a detail of physics or biology wrong. Readers, on the other hand, needed to be scientifically literate to appreciate the full beauty of what the authors were doing.

There was also a political aura that went with the hard-SF style, one exemplified by Campbell and right-hand man Robert Heinlein. That tradition was of ornery and insistant individualism, veneration of the competent man, an instinctive distrust of coercive social engineering and a rock-ribbed objectivism that that valued knowing how things work and treated all political ideologizing with suspicion. Exceptions like Asimov’s Foundation novels only threw the implicit politics of most other Campbellian SF into sharper relief.

At the time, this very American position was generally thought of by both allies and opponents as a conservative or right-wing one. But the SF community’s version was never conservative in the strict sense of venerating past social norms — how could it be, when SF literature cheerfully contemplated radical changes in social arrangements and even human nature itself? SF’s insistent individualism also led it to reject racism and feature strong female characters decades before the rise of political correctness ritualized these behaviors in other forms of art.

Okay, you know I try to steer Castalia House blog away from politics. But let’s talk about this. The Hard SF that Raymond is talking about here was part of a larger culture war against the previous science fiction authors that were (on balance) unselfconsciously Western, Christian, and American in their outlook. Everything that we complain about ruining science fiction today came in right alongside Campbell’s efforts.

This, by the way, is the root cause of why people are upset with the sort of literary criticism we do here at Castalia House. They see that an essentially Christian frame is persuasive, exciting, provacative, and effective… but they’ve been programmed to think that the right thing for Christians to do is simply stand aside and concede ground generation after generation in the culture wars. Far from driving people away, it grows readership like nothing else. In your head you think this is a losing strategy. But compare C. S. Lewis’s Amazon rankings to the sort of thing we’re supposed to like. There really is no doubt about this. We had a winning hand all this time.

Nevertheless, some writers found the confines of the field too narrow, or rejected Campbellian orthodoxy for other reasons. The first revolt against hard SF came in the early 1950s from a group of young writers centered around Frederik Pohl and the Futurians fan club in New York. The Futurians invented a kind of SF in which science was not at the center, and the transformative change motivating the story was not technological but political or social. Much of their output was sharply satirical in tone, and tended to de-emphasize individual heroism. The Futurian masterpiece was the Frederik Pohl/Cyril Kornbluth collaboration The Space Merchants (1956).

The Futurian revolt was political as well as aesthetic. Not until the late 1970s did any the participants admit that many of the key Futurians had histories as ideological Communists or fellow travellers, and that fact remained relatively unknown in the field well into the 1990s. As with later revolts against the Campbellian tradition, part of the motivation was a desire to escape the “conservative” politics that went with that tradition. While the Futurians’ work was well understood at the time to be a poke at the consumer capitalism and smugness of the postwar years, only in retrospect is it clear how much they owed to the Frankfurt school of Marxist critical theory.

But the Futurian revolt was half-hearted, semi-covert, and easily absorbed by the Campbellian mainstream of the SF field; by the mid-1960s, sociological extrapolation had become a standard part of the toolkit even for the old-school Golden Agers, and it never challenged the centrality of hard SF. The Futurians’ Marxist underpinnings lay buried and undiscussed for decades after the fact.

Well it’s obvious those guys were Communists in retrospect, isn’t it? But here’s the thing: it’s only obvious when they’re compared to the pre-Campbellian authors. You know… the same authors that are arbitrarily erased with Raymond’s critical frame.

Another reason why these guys could come in and have a field day is of course the attempt to divorce fantasy from science fiction. Fantasy would maintain its more or less Christian ethos for decades after this, but cut off from its roots as it was, hard SF was easily subverted– to the point where the field became synonymous with subversion. And of course, your rank and file Christian sf fan of today will celebrate these guys and then pat himself on the back for his ability to read around the naked progressivism of the works. Here’s the good news nobody is talking about: science fiction doesn’t have to be like that. Even better, it was just plain awesome this sort of thing came into the picture.

Perception of Campbellian SF as a “right-wing” phenomenon lingered, however, and helped motivate the next revolt in the mid-1960s, around the time I started reading the stuff. The field was in bad shape then, though I lacked the perspective to see so at the time. The death of the pulp-zines in the 1950s had pretty much killed off the SF short-fiction market, and the post-Star-Wars boom that would make SF the second most successful fiction genre after romances was still a decade in the future.

The early Golden Agers were hitting the thirty-year mark in their writing careers, and although some would find a second wind in later decades many were beginning to get a bit stale. Heinlein reached his peak as a writer with 1967’s The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress and, plagued by health problems, began a long decline.

These objective problems combined with, or perhaps led to, an insurgency within the field — the “New Wave”, an attempt to import the techniques and imagery of literary fiction into SF. As with that of the Futurians, the New Wave was both a stylistic revolt and a political one.

Okay, look. This whole “left wing / right wing” dichotomy is absolutely deceptive. All it does is break people down into two groups: Marxists… and people that concede ground to Marxists. Using that terminology more or less makes resistance unthinkable. It’s a nice trick.

What’s going on here is that Campbellian SF is limited. It’s so limited, it limits the market for science fiction. Also… it removes things from the genre that people still crave. So it sets up its own pushback and the pushback comes in strong within a generation.

Now… the thing that most struck me about the New Wave is just how over the top they were in their war on truth, goodness, honor, strength, and everything else. They were in all out war with the remnants of Christian culture that remained in the wider society and would do anything they could to push it out. However… if you look at the work that Nathan Housley and Misha Burnett have been doing… it’s clear that the New Wave was also a second Pulp Revolution. And this makes sense, really. Because New Wave books were right alongside classic pulp when it came to the list of most influential books in the genesis of role-playing games. The stuff that was more or less irrelevant from a gaming standpoint…? That would be all the big time Campbellian authors that we’re supposed to revere.

News flash: we don’t.

The New Wave’s inventors (notably Michael Moorcock, J.G. Ballard and Brian Aldiss) were British socialists and Marxists who rejected individualism, linear exposition, happy endings, scientific rigor and the U.S.’s cultural hegemony over the SF field in one fell swoop. The New Wave’s later American exponents were strongly associated with the New Left and opposition to the Vietnam War, leading to some rancorous public disputes in which politics was tangled together with definitional questions about the nature of SF and the direction of the field.

But the New Wave, after 1965, was not so easily dismissed or assimilated as the Futurians had been. Amidst a great deal of self-indulgent crap and drug-fueled psychedelizing, there shone a few jewels — Brian Aldiss’s Hothouse stories (1961, retrospectively recruited into the post-1965 New Wave by their author) Langdon Jones’s The Great Clock (1966), Phillip José Farmer’s Riders of the Purple Wage (1967), Harlan Ellison’s I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream (1967), and Fritz Leiber’s One Station of the Way (1968) stand out as examples.

As with the Futurians, the larger SF field rapidly absorbed some New Wave techniques and concerns. Notably, the New Wavers broke the SF taboo on writing about sex in any but the most cryptically coded ways, a stricture previously so rigid that only Heinlein himself had had the stature to really break it, in Stranger In A Strange Land (1961) — a book that helped shape the hippie counterculture of the later 1960s.

But the New Wave also exacerbated long-standing critical arguments about the nature of science fiction itself, and briefly threatened to displace hard SF from the center of the field. Brian Aldiss’s 1969 dismissal of space exploration as “an old-fashioned diversion conducted with infertile phallic symbols” was typical New Wave rhetoric, and looked like it might have some legs at the time.

Okay, finally something I can agree with here: there are jewels in every age of science fiction. And to the people that keep telling me that Appendix N is just a list of books that Gygax liked: notice the overlap between “Gary’s list” and Raymond’s jewels here. Half of those authors are Appendix N… the other was a major inspiration to the Gamma World game. That’s not an accident.

Now… as to the rest of Raymond’s essay, it’s boring. In the first place, science fiction and fantasy after nineteen-eighty is boring in and of itself. In the second… his commentary basically boils down to just saying “I like libertarianism and hard sf and the only time something awesome happens is when those two things get together.” And that’s cool. Everybody’s got their own opinions and they can knock themselves out talking about it. It doesn’t bother me at all. But again, the critical frame he takes for granted arbitrarily assumes that about one third of science fiction’s history never happened.

The only thing that poses a threat to his claims…? Why, conveniently enough it’s all disqualified from being taken seriously even for a moment. That’s stupid. Petty. Arrogant. Disingenuous. Ugly. Small. Obnoxious. Ignorant.

You want us to stand down. You want the pulp revolutionaries to dial it back. But sorry… it’s just not going to happen. When they realize the extent they’ve been lied to… when they realize just how much we’ve lost as a consequence of these kinds of shenanigans, they get mad as hell.

You’re not going to stop them.

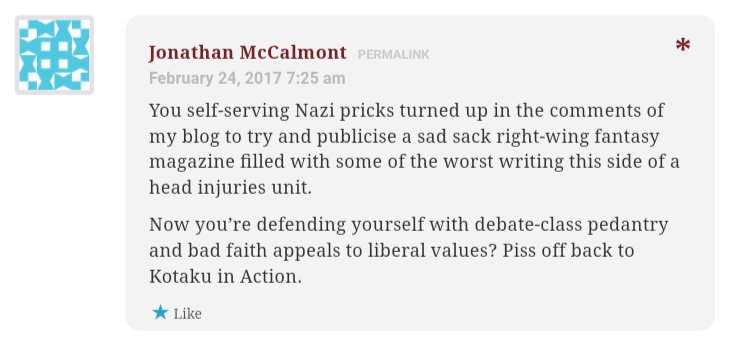

Yeah, um, Jonathan…last time I checked, he has control over his comments. If he can’t abide them, he can delete them.

More to the point, if you don’t want comments, why open them? And if you think it’s inappropriate to comment in someone else’s blog, well, you’ve just hypocritically–and vitriolically, I might add–done it yourself, using ad hominem instead of reason and ideas.

So what’s his goal here? Hmm.

Jeffro is a man of thought and ideas. You may not agree with him, but at least he makes a case and tries to respectfully persuade.

But that comment… well, let’s just say that anyone that opens with “You self-serving Nazi pricks” has already conceded the battlefield of the mind and bunkered himself into an extremist position fortified by little but poisonous, childish emotion.

“To be blunt, I don’t think that genre fandom survived the culture wars of 2015”

Sweet.

“Nerd culture”, “fandom”, whatever, needs to die as it pollutes and ruins everything it embraces into its fold.

I don’t think Raymond knows the actual definition of “McGuffin”:

https://infogalactic.com/info/MacGuffin

I love that rant quoted at the end of your post.

PulpRev is coming.

I indeed don’t know who that guy is, but according to wikipedia he is right-libertarian, pro-gun, neo-pagan, question climate change. So, if nothing else, he isn’t yet another far left character.

So I guess this proves how broad and potent this narrative is, in that such a broad spectrum of people accepts it 100% uncritically.

As for that quoted comment at the end, I would advise against giving any attention to creatures like that one. People like that will never give you a fair shake, so you are basically just giving attention and pageviews to another random, far left geek “analyst”.

-

Well, core is much the same as that peddled by the Marxist writers and reader, only in his case it is viewed trough different ideological lenses, ie Randian “Libertarians vs. Socialists” ones.

I’ll quote Tomberg here:

“A person who has had the misfortune to fall victim to the spell of a philosophical system (and the spells of sorcerers are mere trifles in comparison to the disastrous effect of the spell of a philosophical system!) can no longer see the world, or people, or historic events, as they are; he sees everything only through the distorting prism of the system by which he is possessed.”

Many months back, this essay by ESR opened up my eyes to the Futurians and much of the history of science fiction. I have since disagreed with many of the conclusions of this essay, as, rather than a generally libertarian genre periodically invaded by socialism, I see science fiction as a genre crippled by the overwhelming fear that someone reading it might be a libertarian. However, without it, I would not be reading and writing on sff and pulp history.

To the detractors, I say you use the phrase VD gave us: “We. Don’t. Care.”

Any chance down the road, Castalia will be able to publish something like an Appendix N Reader…a collection of short stories by those authors that just are not in print anymore?

-

I hope so. I know that there were inquiries about Castalia venturing into reprinting older out-of-print fiction from /relevant to Appendix N, both in the comments here and elsewhere. I don’t remember seeing any direct answers, though.

-

Superversive Press has also been talking about that tentatively.

-

-

It’s got my vote, even though I basically have all that stuff.

This is a very good place to define our terms and really focus on what this call for moderation might mean and how it might actually be for our benefit.

There’s a particular kind of, I don’t know, mindset rhetoric? Associated with, especially, Vox Day. When he’s talking, everything he publishes is the best thing ever and everything competitors publish is rotten trash. It’s a promotion technique, it gets people fired up, it’s not something I’d want to do but it seems to be working for him. Here’s the problem, though, especially as it pertains to Pulp Revolution vs. Rabid Puppies.

A big reason Cirsova fired up was the quality of the Rabids’ Hugo picks. They were, more or less, the best non-pink SF they could lay their hands on, that year. Their writing quality was in many ways superior to the howlers that actually won awards, but altogether they weren’t really that great.

Now if you’re trying to show off the best of SFF that year, that’s fine, but the mindset rhetoric took off among the right-wing whispernet that the Rabid picks were worthy to stand among giants, that they were what real SFF always wanted to be, that they towered like giants above the slovenly pink/Torlock set. And they didn’t. I mean, they were better and I’d rather read them, no question, but they weren’t the very absolute greatest things ever written, and I blame mindset rhetoric for giving anyone on either side the impression that anyone thought that.

The reason this is important for a movement attempting to get off the ground is that the spirit of pulp allows for a lot of bad stories, and we are going to write a lot of bad stories. In ten years we’ll look back and say, “oh yeah, that one was real fun to write but it just didn’t come together” and someone else will say “I thought so too but I never told you because the next thing you wrote was so good” or something like that, because we’re developing authors right now and very few people start off as masters. We’re going to need to be very critical and very accepting of criticism, which we have an advantage in because we’re such great friends.

I know it doesn’t seem like knocking Asimov has anything to do with this, but I want to try to press the claim that tooting our horns about how great pulps are and how much Campbell sucks can lead to complacency about the pulps, and in turn to complacency about the Pulp Revolution, until someone’s crowing about how the latest fan-fiction-level twelve-page novelette someone in PulpRev just published beats anything Asimov ever wrote, and we’re all just patting each other on the back.

-

And let me head off a potential misunderstanding by stating that I do expect PulpRev to take off and to make enduring classics, and I believe we have a tremendous advantage from our inspiration material that will make our signal:noise ratio better than most lit movements in the last century. I’m not saying everything we publish will be bad. I’m trying to make room for the things we publish that are bad. Because I am going to publish some bad things and I don’t want anyone to get the wrong idea about them.

-

Well, I thought the Asimov bashing was over the top. His opposition to heroic fiction is admittedly repulsive and he had his flaws as a writer, but to make comments like “The three laws of robotics weren’t that influential”, or to claim that he was just total shit and never wrote anything good…

…Yeah. That’s completely absurd. Asimov has a ton of excellent short stories, and “The Caves of Steel” is an great novel.

Like, people look at “The Evitable Conflict” and claim the point of view it peddles is repulsive and creepy. But it’s not as if Asimov didn’t know it was creepy; the ending of “I, Robot” makes it very clear that he knew full well what he was doing (and interestingly enough, the “problem” of the Machines is solved when they voluntarily shut themselves down). While he did engage in strawmen at times – everyone does – it’s not as if he was totally ignorant of opposing points of view either.

There’s a whole article on Wikipedia/Infogalactic about how much influence the Three Laws had on science fiction. Maybe he didn’t have the influence of ERB, but he is most certainly one of the most influential sci-fi writers of all time.

-

Also, some of the Rabid picks WERE worthy to stand among the giants – “Pale Realms of Shade” by John C. Wright is an instant classic as far as I’m concerned.

I do think you’re overstating the case. One can say the pulps are undervalued (which they are) without calling the post-Campbell writers “collectively inferior.” I don’t see how that’s any different from the current crop of Social Justice SF Warriors dumping on the Campbell era for being too white and male.

Or, more simply: if you actually think The Legion of Space is a better book than Starship Troopers, I’ll meet you for rayguns at dawn.

Unlike partisans who infiltrate a genre with the goal of “improving” it, most people who look back at healthier literary times read and talk about what they read because it’s a pleasure. It’s entertainment. They are in it for the fun. It should not surprise that many people don’t have the energy or disposition to be aggressive, even if they know it could be useful.

But meh, I don’t think it matters much. To each his own style.

“if you actually think The Legion of Space is a better book than Starship Troopers, I’ll meet you for rayguns at dawn.”

No, but I would argue that Raiders of the Second Moon is probably better than anything else ever.

-

“Raiders of the Second Moon is probably better than anything else ever.”

!!!!Link!!!!

-

How in hell did I miss that the first time around? Thanks for the link, Hooc. I posted a fairly cool link to an Andre Norton interview over there just now.

-

I’ll just add that Ramble House is more than legit, since they were mentioned there. They actually sell electronic versions for their more recent releases too, only they don’t put them up on Amazon (for whatever reason) so they need be ordered trough their site. Only issue is that Mr. Tucker may take some time to respond, but every single time he sent me the files before I sent the payment.I actually picked up several volumes from KEW’s fabulous list of horror novels from them.

-

“And you know Castalia House publishes a whole line of Heinleinesque juveniles, right…?”

And the next one is 80% finished!

“They see that an essentially Christian frame is persuasive, exciting, provacative, and effective…”

Which is the nice thing about indie and CH publishing – one can write in a Christian frame to the heart’s content.

-

Great! I really enjoy these books!

If the engineering in your stories is perfectly in tune with existing and plausible tech you can still write a successful story. If the characters in your story behave in ways that are not plausible or believable, you cannot write a successful story.

It’s really just that simple. The tech in the pulps might have been goofy, but the characters were magnificent. The tech might have been great in the follow on revolutions* might have been great, but the characters were flat and acted in ways that did not resonate with readers. So sci-fi readers flocked to the exits.

*One could argue that failing to understand human psychology (and religion is a huge chunk of that) represents a serious failing of future-tech for post-1940 authors. I haven’t sat down and noodled that chain of thought all the way through, but it certainly passes the smell test.

-

“One could argue that failing to understand human psychology…”

Yep, that’s a big one. Worshipping at the altar of Locke’s idiotic Blank Slate theory has crippled SF since the ’40s. Just like Marxism and all the other -isms preaching the possibility of an earthly Utopia, nearly all of the future utopias envisioned by SF authors cling with a deathgrip to the idea that Mankind can be socially engineered into perfection. Neither Poul Anderson nor Jack Vance nor Frank Herbert ever bought into that.

Blank Slateism is also at the root of the idea that human genders are interchangeable and endlessly fluid.

Every day, science is proving that the mind is hardwired for numerous things. They would include tribalism, a need for heirarchy and a tendency to violence.

Locke’s theory has left millions dead and SF in shambles.

-

I’ll add Cordwainer Smith to that list, even though his output was sadly relatively meager. In his Instrumentality cycle, era where human civilisation is hivemind-like, roles and length of life are determined on birth, nations and religions are eliminated, and individuality is utterly suppressed (basically, the sort of socialist Utopia Asimov or Clarke would be salivating over, as do most of their successors) is presented as mankind’s bleak LOW POINT. It was incredibly refreshing for me to encounter that sort of worldview in SF from that era back when I first started reading his short stories.

-

“There’s bit of a push right now for some of us to moderate our tone.”

Speaking as both the Lead Editor of Castalia House and a daily reader of this blog, my opinion is unequivocal: No, absolutely not.

Moderates ALWAYS advise genteel surrender, no matter what the subject happens to be. It is always wise to ignore them.

Jeffro and the other Castalia contributors have hit the ground running in 2017, and if they continue in this vein, this will be openly acknowledged to be the most important blog in science fiction within two years.

“When he’s talking, everything he publishes is the best thing ever and everything competitors publish is rotten trash.”

That is absolutely false. Certainly some of the things we publish are the best things out there. There is no one – no one – in the military world to rival Martin van Creveld and William S. Lind. There are only two science fiction authors writing at John C. Wright’s level, Gene Wolfe and China Mieville.

Sadly, we have no one to rival NN Taleb or Peter Turchin, at least, not yet.

But do I think any fair reading will conclude that the average Castalia House novel is considerably better than the average Tor or Orbit or Daw or even Baen novel. I wouldn’t publish most of the books they choose to publish.

We may not achieve greatness most of the time, but at least we pursue it rather than social justice, racial equality, and BLTG propaganda.

-

Hyperbole aside, I hope you get my point. Not all of your readers are as savvy as you are, and it’s easy for footsoldiers to turn into commissars.

-

You don’t need to remind me that a lot of bad stories are going to be written. I daresay I see a lot more of them than you do.

One hopes Castalia won’t be responsible for publishing very many of them.

-

Producing tent-poles isn’t necessarily bad so long as you also try to produce timeless works of art (assuming that is your goal).

“The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

-Theodore Roosevelt, Citizenship in a Republic

-

-

“On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen—but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—and I will be heard. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal and hasten the resurrection of the dead.”

-William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator, issue 1

-

People come here for the Western Civilization Steak, let other places serve the Tranny Crack Ho Soup.

-

“No soup for you!”

-

This is debate I like to see.

On Burroughs and Howard as revolutionaries–I think it’s better to label them as founders. There wasn’t any establishment for them to have a “revolution” against. The original pulps were wide open and writers could strike out in whatever direction they pleased. It’s only when they hit the limits of markets and paper rationing that writers started trying to drive each other out of the field.

And I don’t want to encourage moderation in force. What I’d like to see is better aim. Sure, it’s easy to shoot at your allies. They’re right next to you. Enemies are harder to reach. In the 21st century readers of Pulp and Campbellian fiction overlap, and are strugging against an establishment that’s overrun with people pushing gray goo on us with no virtues at all, heroic or scientific.

Jonathan McCalmont hates the Campbellians as much as he does the pulps. We should stand together against him.

-

Karl very eloquently makes the point I’ve been trying to put across.

Look, I’m an unapologetic writer of Campbellian fiction. I like getting the science right. And I’m seriously worried about SF as a commercial genre disappearing as it gets more and more focused on leftist virtue-signaling rather than its natural market. The Pulp Renaissance has been a very encouraging development, but if it’s going to degenerate into a different tribe issuing anathemas and proscriptions, then I guess I’m going to have to start writing spy thrillers or something.

-

Seconded (er, thirded) from a pure fan perspective. Fans can’t be prevented from arguing about who’s best, but we ought to be able to see the merits of both pulp and Campbellian SF.

IMO (and just my humble, irrelevant IMO) focus should be to resurrect the sort of of fiction that was presented as passe, both by getting people to read forgotten older authors of quality and by having people produce fiction that is inspired by them or is simply outside the current mainstream mold as dictated by TOR, academia and the like.

I’ve said this before, i don’t like Asimov but I neither want him character assassinated nor do I want fiction of that sort in any way smeared or eliminated.

That is what THEY do.

They ask people to choose, but you don’t have to, you should offer them variety and endless possibilities without dictating specific literary, genre, social, political molds.

On the current Campbel/Pulp argument:

1/ Mulling over the difference between accuracy and realism. The drive to make a story better fit science, geography, or culture is a long-standing tradition, seen in the pulps, in Verne, and even earlier. It is possible to be fantastic and accurate, as the Shadow and Louis L’Amour show…

2/ Realism, however, is the idea that only the stories of the everyman and that only everyday and banal activities and experiences are worth writing about. This idea is anathema to any sort of fantastic literature. The adoption of this idea, typically in 20 year cycles, has driven down sales in sff.

3/ PulpRev has recently come under fire by Campbell fans for its criticism of Campbell writers. It is not the accuracy of the Campbell writers we object to, but the realism of those writers. That realism allowed more fanatical realists – such as the Futurians – to enter the genre…

4/ It is this increasing drive toward realism that it is the source of SFF’s current woes. Almost every major reaction against Campbelline writing is a step further towards realism, further away from heroes and great deeds. Oddly enough, it is the accuracy of the Campbells that the realists protest.

5/ There is room under the Pulp umbrella for the accuracy of Campbell-style writing. There is no room in fantastic literature for realism.

-

Only for magical realism, like Haruki Murakami.

-

I see your point, I think, regarding accuracy and realism, although I would probably define the words a bit differently than you do.

What you are calling accuracy I would call consistency, and would divide it into internal and external consistency.

It’s external consistency that the Futurians were hung up on–they wanted stories in which Mars was described they way that the current astronomical theories described Mars. From a standpoint of internal consistency, however, it doesn’t matter is Burrough’s Barsoom resembles modern theories of the conditions on Mars, what matters is that the dead sea bottoms of Barsoom are always dead sea bottoms, and we don’t suddenly encounter an ocean of liquid water when going from Helium to Thark.

Regarding what you call realism, I think the issue is even more complex. I don’t believe that ordinary people and their quotidian concerns are incompatible with either the fantastic or the heroic.

In fact, I would say that the defense of the banal activities and experiences of ordinary life is the basis of heroism. Frodo and Sam were not fighting for a life of adventure, they were in Mordor precisely because they wanted the Shire to remain quiet and simple.

I think that the issue you take exception to is not the inclusion of ordinary people in adventure literature, but rather the assumption that “ordinary” perforce means the lowest common denominator.

I personally believe that heroes are just ordinary people who have found themselves in extraordinary situations and have found it in themselves to rise to the occasion, and that great deeds are generally preformed in defense of a life filled with banal and ordinary.

-

It’s still a work in progress, a first pass.

I am looking for a better label than accuracy, but it is specifically the external consistency, as you’ve labelled it, that I’m looking at.

As for realism, the particular flavor I’m targeting is Howells’ literary realism, or Realism the movement, which purposefully excludes the fantastic and the heroic for the mundane and the everyday. It is the idolatry of the status quo everyday life, not a Frodo or a Sam or an everyman showing courage above their station.

-

I expect that a lot of what passes for “realism” today is tainted by the existentialism of Sartre and Zola.

-

“Tainted” or not, the Literary Realism credo that Howells laid down 150yrs ago fits the bill pretty well. The literati have been dancing to that tune ever since. All of it ultimately goes back to the fetishization of the masses and the “common man” so easily found in Marxism.

-

-

My father (a ww2 vet) and I once had a conversation about ‘heroes’. My father maintained, based on his experiences with medal of honor winners, was that heroes are -not- the standard everyman who suddenly rises to the occasion.

It was his opinion instead that heroes were rough tough bastards. They were often crude, and had come from a harder and tougher background than the average person (or the ‘everyman’). So when things started to go bad or fall apart, they didn’t. They were able to keep doing what they were doing, or do what needed to be done, because they were fighters who did not give up and who did not shy away from what needed to be done to survive.

The first medal of honor winner in the Army Air Corps in ww2 was so rude and crude that they had to shuffle him off out of sight. He was a complete PR nightmare. But he was a hero, even if he didn’t think so. This sort of thing I’ve been told has happened more than once.

When I went through basic survival, they told us stories of pilots who had survived pure hell, and pilots who had given up and died (or committed suicide) because they didn’t want to face surviving, even though their situation wasn’t all that bad.

What they said was that it always comes down to this: What are you willing to do to live? That is a decision everyone makes for themselves when the time comes, and the only reason they even bother with survival training, is to try and give you the skills and the confidence to have the will to survive. They can’t make that decision for you, you will make it yourself when the time comes.

Heroes are the people that have that will. And it just doesn’t appear out of the blue, it’s developed by the life they have lived before, or the ideals that they hold dearly. When ever an ‘everyman’ rises to the challenge, you always find it is because of some aspect of the life they lived. They don’t view what they do as heroic, because to them they’re not doing anything special.

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dean_Howells

In defense of the real, as opposed to the ideal, he wrote,

“I hope the time is coming when not only the artist, but the common, average man, who always ‘has the standard of the arts in his power,’ will have also the courage to apply it, and will reject the ideal grasshopper wherever he finds it, in science, in literature, in art, because it is not ‘simple, natural, and honest,’ because it is not like a real grasshopper. But I will own that I think the time is yet far off, and that the people who have been brought up on the ideal grasshopper, the heroic grasshopper, the impassioned grasshopper, the self-devoted, adventureful, good old romantic card-board grasshopper, must die out before the simple, honest, and natural grasshopper can have a fair field.”[18]

[. . .]

Howells was a Christian socialist whose ideals were greatly influenced by Russian writer Leo Tolstoy.[20]

-

Yep, that’s him. Father of the dime novel and the pulps – because that was the only place left to publish fantastic literature after he was done.

-

“In defense of the real, as opposed to the ideal, he wrote…”

That’s the problem. We have 7+ billion DIFFERENT ideas of what constitutes “real” on this planet. Believing that you know exactly what another person is thinking or why they did something is pure fantasy. So any attempt at “realism” is doomed to be fantasy. Thus, we might as well make fantasies entertaining.

Howells was just attempting ham-fisted social engineering (using capitalist dollars to promote socialism) and, in the process, handicapping true storytellers to give talentless scolds and hacks a shot at literary success. What a self-righteous prig.

-

-

-

I think there is more evidence for the cambellian revolution being a revolution of omission. The pulps are jam packed with brainy heroes. Peculiadur, caspack, the moon pool, ballader john and the whole chuthlu mythos are full of brainy heroes.

-

Lovecraft’s stories had heroes and heroics of all stripes, something folks forget nowadays. I suspect that good chunk of people talk about them based on works they inspired and the pop perception of Lovecraft and his fiction, rather than personal experience.

For example, I saw people being surprise by the fact that, in CoC, Cthulhu’s rising was prevented by one man, by his sheer willpower and stubbornness.

-

Johansen was a badass.

There is action off-stage in HPL’s stories, just not front stage. In Lovecaft’s opinion, intense, onscreen action (or romance) interfered with creating a mood of fear in a story. Arguable, but that’s how he saw it. That said, he enjoyed several Conan tales, especially the ones where it was horror-action, but no romance.

-

I find it funny that he calls Campbell right wing, when you consider the argument RAH had with him, and why RAH parted ways with him.

I also think some of the authors he holds out as great, sucked. Even though we are almost the same age, we read a very different mix of scifi, and therefore have fairly different opinions. Maybe because I lived in NY I had access to a broader market? I don’t know.