Last week, Jill commented on the madness and prophecy of Philip K. Dick:

And then you have those oddities, such as Phillip K. Dick, who was clearly insane, but had uncanny predictions about the future. Most sci fi writers just plunge ahead and get things wrong or a little off, though.

Fortunately for the sane and otherwise occupied, a couple of stalwarts–Pamela Jackson and Jonathan Lethem–have done yeoman’s work in gathering and editing the more than 8,000 pages of correspondence, journals and notes relating to Phil Dick’s personal/cosmic 2-3-74 event. Although it is condensed to a mere 900 pages, and one must imagine that there are entire office boxes full of scratchings that haven’t even been scanned yet, it is a phenomenal introduction to the broad-reaching vision, experience and uncertain insight of one of the most beloved of science fiction’s “Damaged and Dangerous Men.”

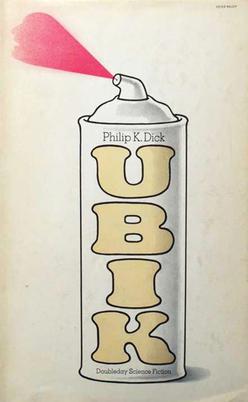

Philip K. Dick considered Ubik to be a significant precursor to his 2-3-74 experience.

In The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick, Dick notes (anticipating a somewhat more prestigious essay on semiotics) that error is fundamental to the flexible transmission of meaning. That is, because the mystical experience of writing to anticipate the future will most certainly be inaccurate, one is more likely to anticipate the future by looking to the past…and scrambling it.

His novel Ubik, for example, assumes that the present moment (in-novel) is receiving data transmissions from the future, and is being redeemed by the titular substance, Ubik (which means “everywhere,” as in “ubiquitous.”) But that future data is as fragmented as the ever moving present time, and as spotty as memory.

In writing of time in this way, however, Dick wrote a book that anticipates the future (or, more accurately, June of 1992) quite well. It holds up where other books that took a more literal approach to projecting the future fall apart into an amusing array of bubbletop cars and computers the size of planets.

It is clear in reading his edited Exegesis, that, yes, there may have been something not quite right about Dick’s brain, but one only needs to read his clear-eyed, humble words to know that there was nothing wrong with his mind. If the brutal language of Frank Dec had an expressive and emotive opposite, it might be found in Dick.

What he indicates is that to prepare for the future, one must expect it to arrive in shattered bits. That way, you can be pleasantly surprised on the rare occasion when it does not.

There was this article the other day on Wired about quantum entanglements that prevent us from remembering the future as we do the past. I didn’t really understand it, so I’m not going to pretend to, but your article did remind me of it. It had something to do with becoming correlated with the present…mind trailing off. In any case, in a typical understanding of people who seem to be prophets–in its limited definition of people who can predict the future, not those who speak for God–I would say they are people who understand history and trends, while also understanding that history doesn’t actually repeat itself. And there is no steady, logical path into the future from a human perspective. Well, I mean, there is. You brought up the computers as big as planets, which seemed to be a logical projection due to the size of the early computers. But it’s actually more logical, or practical in any case, to assume that engineers would attempt to make the technology smaller, but with denser capacity. Moore created a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy of that in the 60s, I think. I guess what I’m saying is that it might take a special kind of logic to intuit the future–not an ordinary one. Either that, or some people have found ways to remember the future in fragmented pieces.

PKD was ecstatically gnostic, in that (and I hope I’m portraying him right – it is unfair to condense an 8000+ page quest into so few words) his quest for knowledge was the essence of life. Whereas I might argue that the man who seeks God earnestly will be rewarded with finding Him, PKD’s personal experience that the journey through knowledge was itself divine. In living that way, he anticipated the future (for the sake of his stories) rationally, mystically and through a faith that the timestream was in fact not linear.

In other words, he could count on his childhood experiences or something he saw on television or in a book happening again in a new…and often screwy way.

I think that might be a form of the “special kind of logic” you write of.

I was going to tie-in something about Michael Servetus, the circulation of the blood, the Swedenborg Society and prediction next week, but I think I better do something on explosions instead.

It’s too bad Servetus didn’t predict what would happen when he stopped in Geneva. That was not very forward thinking of him.

I’m not convinced that he did not (a clue for me is in the book that got him killed)…but that’s some science fiction I’ll get into another day, because I need to do a lot more thinking and reading about it.

It’s been an intriguing question for hundreds of years–why DID he stop in Geneva? I would like to see your science fiction answer to that.