CH Blog Flashback: The Dirty Pair and Jesuit Joe

Saturday , 26, August 2023 Uncategorized Leave a comment “We solved every case we worked on. It’s just that the solutions weren’t always pretty. An explosion here, an inferno there, and in the end, we’re left with a mountain of corpses, and, incidentally, a solution.”–Kei, “The Great Adventure of the Dirty Pair”

“We solved every case we worked on. It’s just that the solutions weren’t always pretty. An explosion here, an inferno there, and in the end, we’re left with a mountain of corpses, and, incidentally, a solution.”–Kei, “The Great Adventure of the Dirty Pair”

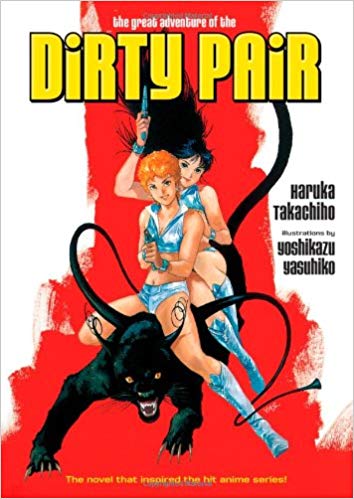

When science fiction writer A. Bertram Chandler visited Japan in the late 1970s, he had no idea that a stray comment would spark a multimedia science fiction franchise. When his hosts, including Haruka Takachiho of Crusher Joe fame, took Chandler to see a joshi (women’s) wrestling match, the antics of Takachiho’s assistants prompted Chandler to say, “”the two women in the ring may be the Beauty Pair, but those two with you ought to be called ‘the Dirty Pair’.” That stray comment sparked a novella that mixed Western pulp science fiction, Japanese joshi wrestling and idol singing, and a double-helping of chaos into what would be a classic raygun romance–if the Dirty Pair’s infamy didn’t keep scaring off potential suitors.

The Lovely Angels (don’t ever call them the Dirty Pair to their faces) is the code name for a pair of young trouble consultants. Kei, the narrator for the stories, is a brash, boastful, and lively hothead lifted from the covers of the pulps. Her partner, Yuri, is a demure Japanese beauty that acts as the brake to Kei’s recklessness–and the occasional focus of Kei’s jealousy as well. Together, Kei and Yuri form a set of complementary opposites–and a psionic duo straight out of John W. Campbell’s dreams. The resulting property damage, however, is straight out of a nightmare. In the best tradition of wrestling heels, the ensuing chaos is never quite their fault.

Like many Japanese stories, The Great Adventure of the Dirty Pair wears its inspirations on its sleeve. From wrestling, the series gets the outfits, names such as Lucha and the WWWA ( World Welfare Works Association from the World Women’s Wrestling Association), Kei and Yuri’s larger than life personalities, and their heelish yet sincere protests that the disasters in their wake are never their fault. The names Kei and Yuri are taken from the same assistants who entertained Chandler. From American science fiction pulps, the Dirty Pair steal liberally. Rayguns, heatguns, flying saucers, and Campbelline psionics feature prominently in the stories. Kei’s hair and build is classic pulp cover-girl, while the interior art is a mix of 1940s Weird Tales interior art and manga. Their adventures are the sort of trigger happy-detective story that filled the hero pulps. And, yes, that is a coeurl Kei and Yuri are riding on the cover, complete with the nickname “Black Destroyer”–and the special diet and property damage required by a hyper-intelligent alien cat. The result is a strange East-meets-West version of Northwest Smith, if Northwest Smith and Yarol were replaced by sorority girls.

While the two novellas in The Great Adventure of the Dirty Pair are standard futuristic versions of crime tales, complete with the requisite twists and betrayals, Kei’s narrative voice is the star of the show. Her larger-than-life exuberance practically drips from each word, even after translation into English. Some of this is due to Kei’s constant wrestling-style self-promotion, but Dark Horse did a masterful job in translation. Few English-language science fiction stories–and almost no light novels translated since–have such a vivid, unrestrained, and selfish voice animating their words, much less one trying to style herself as a heartbreaker and a lifetaker to potential partners and rivals alike.

At the end, when the villains are arrested, all the worlds are wrecked, and the refugees resettled, the Dirty Pair novel always preserves its pulpy sincerity, complete with the foreboding that the Lovely Angels will soon wreak their accidental havoc on a new world.

“You took one of my old uniforms from that hut on the Caribou River. When I arrived at Headquarters to receive my promotion to sergeant, I was informed of a corporal of the Mounted Police who had a habit of scalping enemies, of stabbing the hands of priests, of saving the parents of kidnapped children, and of guessing the contents of ministerial letters…”–Sergeant Fox

“You took one of my old uniforms from that hut on the Caribou River. When I arrived at Headquarters to receive my promotion to sergeant, I was informed of a corporal of the Mounted Police who had a habit of scalping enemies, of stabbing the hands of priests, of saving the parents of kidnapped children, and of guessing the contents of ministerial letters…”–Sergeant Fox

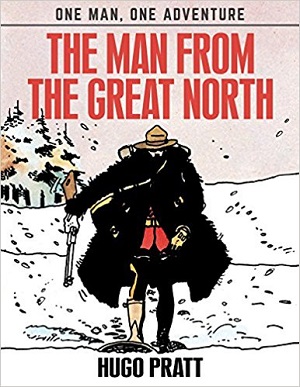

As mentioned in Castalia House’s Picks of 2017, one of the stories of the year overwhelmed by the bluster of Marvel and Comicsgate was the steady release of seminal European comics into the American market. From the 30th anniversary of The Obscure Cities: Samaris, to the conclusion of Valerian and Laureline, or the continued wanderings of Corto Maltese, these titles found their way into the hands of eager readers. At the very end of the year, IDW published for the first time in English the adventure of Jesuit Joe, one of the most compelling characters penned by Hugo Pratt. In IDW’s The Man From the Great North, elsewhere eponymously named Jesuit Joe, the imposter Mountie treks across the snows of 1912 Canada in search of his sister and suffering, pursued by Sergeant Fox.

To adhere to Pratt’s preferred version of this comic, the IDW edition inserts the rough storyboards Pratt drew for the Jesuit Joe movie. The unfinished art can be jarring, especially after pages of Pratt’s typical thick-lined polish. As for the content, it falls in an uneasy balance between fanservice and useful explanations. And by fanservice, I don’t mean the addition of nudity, but the insertion of Jesuit Joe’s previously unknown literary predilections, a preference characteristic of Pratt’s other famous wanderer, Corto Maltese. But the added Sergeant Fox scenes flesh out his pursuit of Jesuit Joe as well as Jesuit Joe’s connection to Canadian history. Still, the storyboard additions are verbose digressions compared to the original terse comic. The art style of the storyboards is distinct enough so that readers who wish might skip past them. I recommend this reading–but only on the second or subsequent reads.

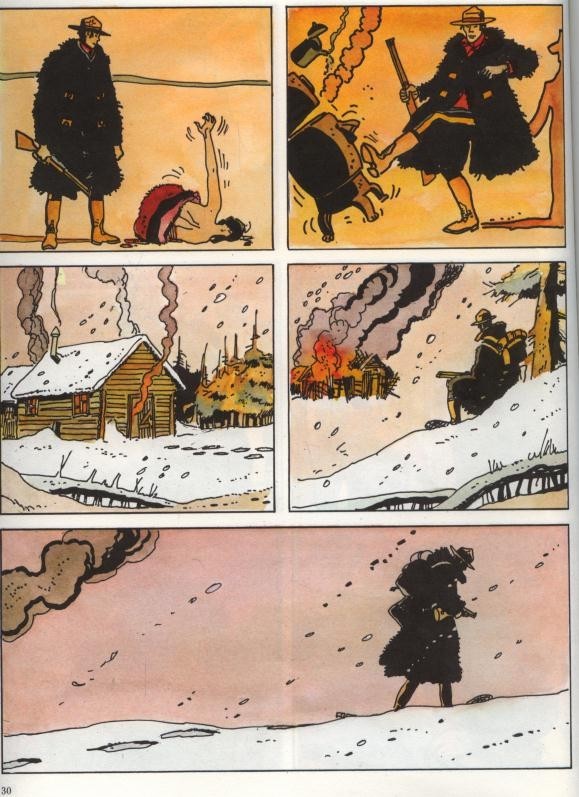

Elsewhere, Pratt’s winter tales glory in the stark contrast of black and white, whether in Siberia, Canada, or Alaska. In The Man From the Great North, Pratt instead colored the same stark art, with the grays and blues of four color comics. Combined with the heavy lines and shadows of Pratt’s artwork, the panels convey the featureless desolation of winter more effectively than a more detailed style. But when textures need more detail, such as outlining a log cabin, Pratt does not shy away from including it. The art may be simpler than today’s extravagances, but its stark nature serves as a countermelody to the complexity of Jesuit Joe as a character. And simple is not unsophisticated–or easy.

This is the third time I’ve grappled with The Man From the Great North in an attempt to review it for Castalia House. The difficulty comes down to Jesuit Joe, the half-Indian impostor dressed in the red serge of the North West Mounted Police. At home in neither the world of the White Man or the Red, like many of Hugo Pratt’s characters, Jesuit Joe is a wanderer with a strong moral code, although one somewhat orthogonal to everyone else’s. But divining that code from the terse and laconic panels is not easy. Jesuit Joe shows occasional glimpses of capriciousness, but also an Old Testament view of justice, and a mercy he explains away as mere whim. And each can be dealt out with a sharp word or a bullet. Jesuit Joe explains his philosophy as he terrorizes Father La Salle for information as suffering for heaven. However, Jesuit Joe notes that he never suffered, but could only bring it to others. But Jesuit Joe’s words are often at cross-purposes to his actions, so there’s uncertainty to whether Jesuit Joe was telling the truth or merely adding to Father La Salle’s suffering. What we’re left with is a man wearing a uniform that is not his rendering a more faithful service in his crime than many policemen with their oaths. And the air of paradox and uncertainty around Jesuit Joe continues to the end of the story, creating the most asked question of Hugo Pratt’s career:

“What happened to Jesuit Joe?”

Discerning that, like much about this man from the Great North, is left to fuel the reader’s imagination.

Please give us your valuable comment