They told me they needed me to go to Samaris, as the rumors had been going on too long…

They told me they needed me to go to Samaris, as the rumors had been going on too long…

…and the only way to put a stop to them was to send someone there to see what was really happening.

On a counter-Earth 180 degrees removed from our own, a young officer in service to the city of Xhystos, Franz Bauer, is given a mission of vital importance. He volunteers to go to the mysterious city of Samaris, thought by Xhystos to be the foreign source of the malaise affecting its culture. Many have been sent to the fabled Walls of Samaris, yet none have returned. Driven by ambition, Franz ignores the objections of his friends and sets out for Samaris.

Perhaps he should have listened.

Thus begins the first of the tales of Les Cités obscures, known now in English as The Obscure Cities, a multi-decade fantasy written by Benoît Peeters and drawn by François Schuiten. Sadly, most of the series of this classic French bande dessinee remains untranslated in English, and many of the translated volumes fall readily out of print. Scarcity has driven up the esteem of this series, both in English and in French, yet the quality matches its reputation through mixing gorgeous architecture in the backgrounds and philosophical storytelling. As Julian Darius wrote in his overview for the Sequart Organization:

But The Obscure Cities? It’s pretty much what Americans want French comics to be. Intoxicatingly beautiful. Elegant, even. Willing to experiment. And smart in a way that it’s easy to lose yourself in the rich resonance.

There is a bit of subtle wordplay hidden by translation to the title of The Obscure Cities. Like Franz Bauer, we see through to the meaning dimly, knowing and perceiving in part. While these regions are not well known, the original French has connotations of darkness, menace, and hiding. It’s a proper title for a story driven by one central, even paranoid, concern: what mystery lays in the heart of Samaris’s walls with its carnivorous plant heraldry?

Franz arrives to the wonder of Samaris, a walled city that can be seen on the horizon nearly two weeks before arriving. The city combines a vast sprawling footprint with a bizarre mix of architectural styles from different civilizations and eras. However, the high society is confined to a narrow, even homely, section of the city. Franz soon falls into a comfortable rut of socials and soirees, but little details keep worrying him.

Why were there never any children in Samaris? Why were so many doors blocked off? Why wasn’t there anything behind the shutters that I pried open?

Franz pokes and pries into these details until he breaks through the facade. Samaris is an empty mechanical city devoted to creating an illusion of civilization and society. Every single person he talked to since arriving had been a puppet or mechanism. To what end and why? Even Franz does not know. He did find a single book explaining Samaris, but much of its meaning remained obscured by metaphor. And like other forbidden books, what little knowledge Franz could gleam drives him mad. He manages to escape Samaris and return to Xhystos, however, what he finds when he returns is just as artificial and disturbing as Samaris.

In many ways, Samaris serves as a reflection of Xhystos. Whether it be the unsatisfying fakeness of high society or the impersonal mechanisms running the city, Franz finds analogues in both cities. While he is not satisfied in either location, Franz does prefer the one that casts the illusion of care, even as both cities mistreat him for their own purposes.

Franz also learns the traveler’s curse. As Sedulius of Liege wrote:

To go to Rome

is little profit, endless pain;

the master that you seek in Rome

you find at home or seek in vain.

Franz’s travels never let him escape the discontent with society that remained with him. And the constant attempts to escape thrust him into successively direr circumstances.

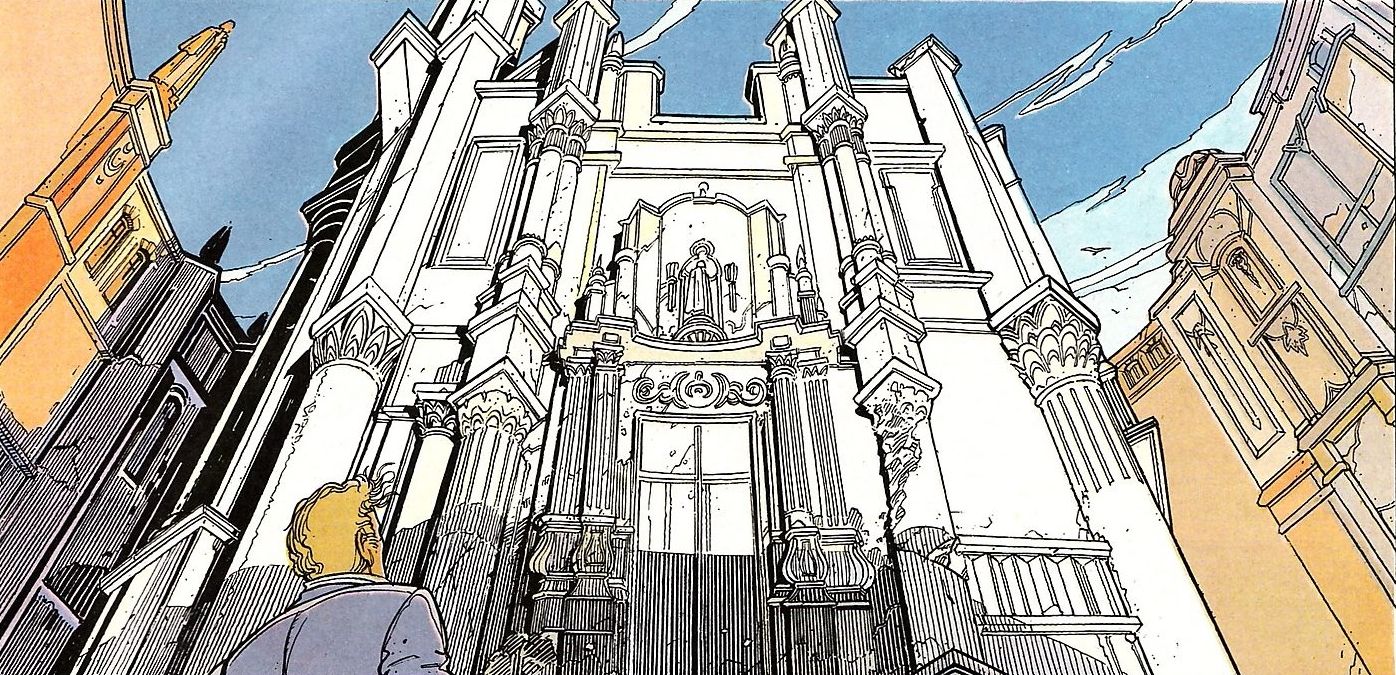

It is to Peeters’ credit that the investigation of Samaris provoke these and other observations about human nature through masterful use of contrast and structure. But words and dialogue are only part of the appeal of the Great Walls of Samaris. From the beginning, we are treated to wondrous cityscapes like the one below:

Schuiten’s love for architecture, instilled in his childhood, is on full display throughout the 64 pages. Instead of paintings, the illusion is of flipping through modeled blueprints on a drafting table. Straight lines and pronounced perspective abound, giving an almost mechanical feel to the clockwork city. The anarchonistic European styles also add to the unsettling feel that grows throughout the story. When it comes time to draw the tracks, girders, and epicycles behind Samaris, Schuiten’s drafting-inspired art is an excellent match, and contrasts with the exterior facades. The artwork deserves lingering attention, just as the story provokes contemplation.

If you desire a tour of Samaris and the other Obscure Cities, try to find the recent IDW collections. Their translations are closer to the original French, and their version of Samaris also includes the Mysteries of Pahry, an early collection of stories from the Obscure Cities. But be warned:

Samaris has always been and will always be, like water that replenishes itself every day. It will seize the likeness of those it captures and make an effigy.

Please give us your valuable comment