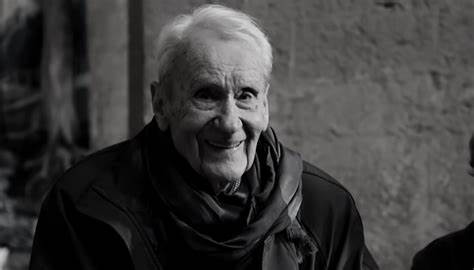

Christopher Tolkien: A Centennial Remembrance

Saturday , 23, November 2024 J. R. R. Tolkien Leave a commentThis is a guest post by Deuce:

Yesterday marked the centennial of Christopher Tolkien‘s birth. Such an event is not a minor occasion. In his own way, Christopher was a titanic figure within the sphere of twentieth-century fantasy. In addition to that, he was a good man and an exemplary son. I intend to demonstrate all those points in my post below.

Christopher was born in Leeds, England, the third and final son of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. He was raised in Oxford, where his father held the post of Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford. It should be noted that Christopher attended the Dragon School in Oxford as a boy. You can’t make this stuff up.

Christopher’s father was a hard-working professor of philology, but JRRT loved to regale his children with tales of Elves and monsters. Christopher paid close attention. As he put it in his foreword to The Hobbit:

” [O]n one occasion I interrupted: ‘Last time, you said Bilbo’s front door was blue, and you said Thorin had a golden tassel on his hood, but you’ve just said that Bilbo’s front door was green and that Thorin’s hood was silver’; at which point my father muttered ‘Damn the boy,’ and then ‘strode across the room’ to his desk to make a note.”

That love for his father’s fiction and attention to detail would be a hallmark for the rest of Christopher’s life.

Christopher suffered from a heart ailment, but that didn’t stop him from enlisting–at the age of nineteen–in the Royal Air Force in 1943. In 1945, he returned to England and was inducted as a permanent member of the Inklings, the literary club centered around his father and C.S. Lewis. Christopher would end up redrawing his father’s maps of Middle-Earth for the first publication of The Lord of the Rings. Those maps have now been seen by millions of fantasy fans and are iconic amongst aficionados of fantasy cartography.

For the next phase of his life, I can do no better than quote the entry at Tolkien Gateway:

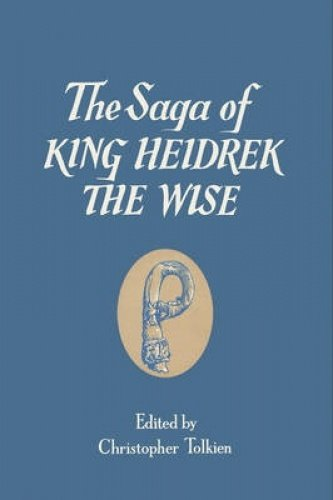

“In 1946 Christopher returned to Trinity College to resume his studies and reading English. For a while his tutor was C.S. Lewis. His thesis was a translation of The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise and he received his B.A. in 1949. Christopher also became a lecturer in Old and Middle English as well as Old Icelandic at Oxford. He worked as an editor on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the Pardoner’s Tale, and the Nun’s Priest’s Tale. From 1963 to 1975 he was a Fellow of New College, Oxford but resigned when he began to devote his time to his father’s literary affairs…”

Just imagine having J.R.R. Tolkien as a father and C.S. Lewis as a tutor. Keep in mind, however, that Christopher grew up in modest, middle-class circumstances. It wasn’t until the success of The Lord of the Rings in the 1960s that JRRT was able to quit jobs like grading papers for other professors.

Christopher was able to follow in his father’s footsteps at Oxford, preparing him for his later work as JRRT’s literary executor. For those enamored of “The Northern Thing”–a term invented by his erstwhile tutor, C.S. Lewis–The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise, translated by Christopher as his thesis project, is well worth reading. The saga is somewhat centered around the cursed sword, Tyrfing. Yes, the same black blade central to Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. The late, great Steve Tompkins wrote a masterful analysis of Tyrfing and its literary “descendants” for The Cimmerian website.

While I’m fully capable of reworking the text, it seems best to simply quote from the Tolkien Gateway site regarding Christopher’s career after his father’s death in 1973:

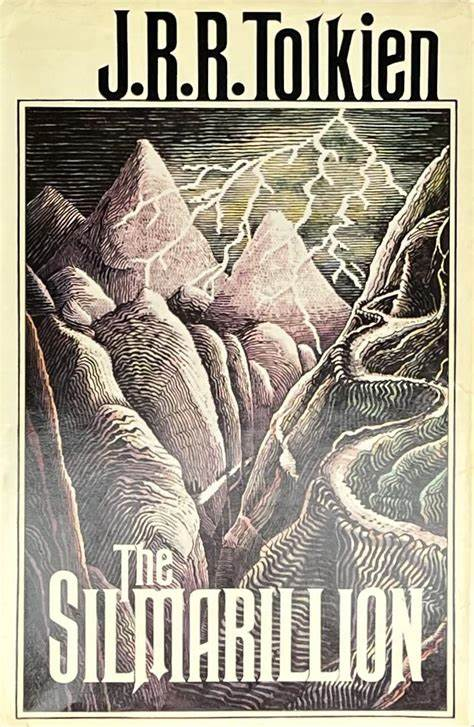

‘In J.R.R. Tolkien’s last will and testament, Christopher was appointed literary executor and granted “full power to publish, edit, alter, rewrite, or complete any work of [his father’s] which may be unpublished at [his] death or to destroy the whole or any part or parts of any such unpublished works”.[6] He embarked on the task of organizing the masses of his father’s notes for subsequent publication; something he would continue to do for the remainder of his life. Much of the material was handwritten, frequently a fair draft was written over a half-erased first draft, and names of characters routinely changed between the beginning and end of the same draft. Deciphering this was an arduous task, and perhaps only someone with personal experience of J.R.R. and the evolution of his stories could have made any sense of it; even so, Christopher has admitted to having to occasionally guess at what his father intended.

With the help of Guy Gavriel Kay he managed to compile The Silmarillion in only four years. During this time, he also edited his father’s translations of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Sir Orfeo. He also worked on the Nomenclature of The Lord of the Rings, which was first published in 1975 as Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings in A Tolkien Compass.

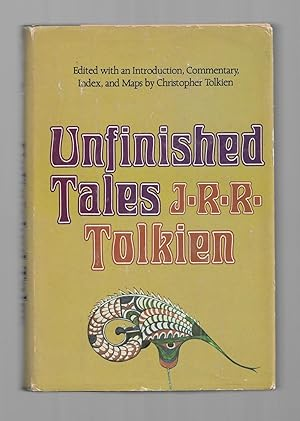

Christopher spent the years after continuing to study his father’s works and taking the responsibilities of the Tolkien Estate. He recorded portions of The Silmarillion in 1977 and 1978 which was issued by Caedmon Records, New York. In 1979 he wrote about his father’s illustrations and drawings for their publication in Tolkien calendars and Pictures by J.R.R. Tolkien. Through 1980 and 1983 Christopher edited Unfinished Tales, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, and The Book of Lost Tales Part One which was the first volume in his twelve volume series of The History of Middle-earth, the last of which was published in 1996. In 1998 he edited a new edition of Tree and Leaf including the poem Mythopoeia. In 2007, he edited The Children of Húrin, the first of the so called Great Tales of Middle-earth. His last publications were the editing of Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary (2014), Beren and Lúthien (2017) and The Fall of Gondolin (2018).

In 2016, Christopher Tolkien was awarded the Bodley Medal, the Bodleian Libraries’ highest honour, for his “editorial work on his father’s manuscripts” and his “academic career at the University of Oxford”.

In August 2017, Christopher Tolkien resigned from his appointment as director of the Tolkien Estate.’

That’s damned near forty-five years in service to his father’s vision.

I became aware of Christopher Tolkien while in junior high. I’d read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as a pre-teen. I wanted to read more. Segue to the Christmas of my eighth-grade year, held in the very house in which I live right now. My mom brought out a present from my Aunt Barbara. I was always Aunt Barbara’s favorite nephew, but she lived in the hinterlands of Montana and a Christmas gift from her wasn’t guaranteed any given year.

That year, she ‘paid’ things off for good, in my opinion. Her present to me was a first edition hardcover of The Silmarillion, a first edition of Unfinished Tales and a couple of scholarly volumes on Tolkien and Middle-Earth–which were uncommon at the time. Mind blown. This matter-of-fact “pioneer woman” out in the wilderness had seen what I wanted and given it to me, along with books of ‘fantasy lit-crit’ that set me on the path that eventually led to me writing this blog post.

Of course, now we come to Christopher “altering” his father’s writings. I can encapsulate numerous discussions I had with midwit nerds during the ’80s and ’90s this way:

“Hurr durrr! I read the Silllamarillion [sic] and it’s OBVIOUS that his son wrote it ALL! What a let-down!”

Christopher did no such thing. Faced with the thankless (and well-nigh impossible) task of collating his father’s writings, he wrote ‘bridging’ passages here n’ there to connect texts sometimes separated by two decades or more. All of which was admitted to in advance.

All of the bitching ended up being a kind of eucatastrophe. Christopher decided to present all of the texts he’d worked with when editing The Silmarillion and then some. The result was “The History of Middle-Earth” volumes. Any nay-sayer could read therein, find all the texts and compare them to what Christopher published in The Silmarillion.

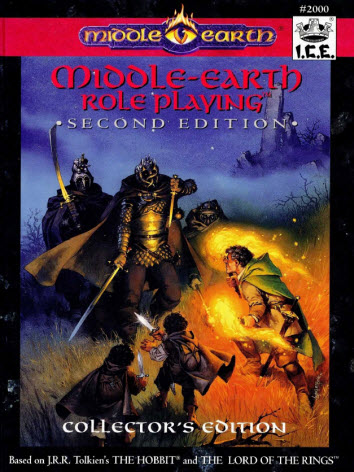

Doing so caused much of the criticism to taper off–except amongst the Secret Kings and ankle-biters, who don’t matter. Meanwhile, Christopher’s “codification” of The Silmarillion provided the extra lore needed by Iron Crown–a name derived from Morgoth’s diadem–to launch their classic Lord of the Rings ‘MERP’ RPG.

Meanwhile, Christopher’s titanic efforts provided material for a solid century of literary criticism and debate–all from the most unimpeachable source imaginable. On top of that, much of the material was cool for its own sake. “The Book of Lost Tales” was radically different from what came later. “Athrabeth” is a gem that every Tolkien uber- fan should read. “The Wanderings of Hurin” demonstrates, again, that JRRT could do grim n’ gritty on par with GRRM.

After the “History of Middle-Earth” was completed, Christopher would go on to expand upon the foundations he’d laid. The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin–each presented in different ways best suited to their unique situations–extracted the ‘Great Tales’ of The Silmarillion from the mass of texts laid out in The History of Middle-Earth volumes. This was an invaluable service to Tolkien fans. In the case of the Húrin book, it produced a minor classic of fantasy that had heretofore not existed.

In addition, Christopher compiled his father’s texts on ‘Dark Age’ classics which influenced the tales of Middle-Earth. The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary and The Fall of Arthur are all worth reading for aficionados of those tales. I treasure my volumes. Within them are insights I have found nowhere else.

All the while, Christopher tirelessly defended his father’s work from those who sought to “interpret” it in a more ‘modern’ fashion. He famously called out Petey Jackson and WETA for their shallow and fatuous ‘interpretation’ of The Lord of the Rings. Rightly so, in my opinion.

Christopher laid down his pen and passed into the West in January of 2020, dying at the age of ninety-five, long-lived like many of his line. He had served England during its finest hour. He was a member of the Inklings, one of the most influential literary ‘clubs’ of all time. He had married and carried on his father’s name. He had defended his father’s legacy against all comers and had expanded that legacy to heights unimaginable when JRRT went to his grave in 1973.

To get a better idea of the man, here is a video compilation of interviews:

Christopher Tolkien VIDEO interview compilation – CleanCut

Raise a glass to the memory of Christopher Tolkien. He fully deserves it.

Please give us your valuable comment