Come, reader. Let us continue the review and commentary of the Conan stories of Robert E Howard. This episode is Tower Of The Elephant, first appearing in in Weird Tales, March 1933.

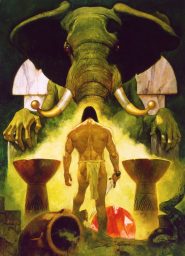

Conan is young here. The internal chronology of the stories is subject to some guesswork. But it is fair to say that this is the second or third tale in Conan’s career, taking place after Frost Giant’s Daughter (1934). We see him for the first time in what will be his signature costume: “naked except for a loin-cloth and his high-strapped sandals.”

I found, as I often do, that not only is Robert E. Howard a better writer than I was able, as a callow youth, to see he was. He also easily surpasses the modern writers attempting to climb his particular dark mountain. From the high peak, brooding, he glares down at inferior writers mocking him, and, coldly, he laughs.

Particularly when Howard is compared with the modern trash that pretends to be fantasy while deconstructing and destroying everything for which the genre stands, he is right to laugh.

Let us list the ways.

Howard, as many pulp-era writers had to be, is a master of structure.

The Tower of the Elephant is divided into three chapters. The first introduces the set-up. In the most lawless quarter of a city of thieves, in a stinking tavern where rogues and lowlifes gather, rumors are spoken of a silvery tower that looms above the city in an isolated garden on a hilltop. In it is a gem of fabled worth and eldritch powers, that is the talisman of a sinister wizard. The tower seems strangely unguarded, or, rather, guarded strangely.

The wall is low, the way is not difficult: but none of the famous thieves will dare approach it. Our very own Conan (whom last we saw as a king) is here a barbaric lad who asks about the tower and the gem, is rudely answered, and rashly vows to make the attempt. Words are exchanged, and a fight ensues. We soon see how tough Conan is.

The second chapter is a heist. We are introduced to Taurus the Prince of Thieves. He and Conan join forces, attempting to elude or outfight the dangerous or unchancy defenders, human or otherwise, guarding the treasure. When even the Princes of Thieves is unable to overcome a particularly strange peril, a second fight ensues. We soon see how tough the Tower is.

The final chapter is pure awesomeness. The weird and supernatural secret of the Tower reveals itself. Even bold Conan, who fears no mortal blade, is petrified, if only for a moment. The dire and supernatural revenge which follows those who meddle in the outer secrets unfolds.

Howard is also the master of the one trick that always seems to elude postmodern writers. He knows how to pen a proper ending: As in a fairy tale of old, Conan is wise enough to obey the supernatural being when it speaks, and a pathway to safety is opened for him. He escapes with his life.

What becomes of the mystic gem that decrees the fates of kingdoms? Read the tale yourself and discover: my lips are sealed.

Howard knows that every story must have a moral core. His particular genius, which was the genius of an era where men were weary of the civilization, and yearned for younger, simpler days, yes, even more savage days, was to call on a Pagan moral core rather than a Christian one. There is no mercy, no faith, no forgiveness in Conan’s world. There is, however, courage and honor, even among thieves. The Conan stories glamorize the barbaric while denigrating the corruptions that dog civilized life.

The writer’s task consist of telling, not merely the events of the tale, but the deeper truth they hide, including odd bits of wisdom:

Civilized men are more discourteous than savages because they know they can be impolite without having their skulls split, as a general thing.

Or:

A civilized man in his position would have sought doubtful refuge in the conclusion that he was insane; it did not occur to the Cimmerian to doubt his senses.

The writer includes not just the world, but the worldview of his tale. In Conan’s world, civilized religion is rotten because civilization is rotten.

He [Conan] did not trouble his head […] he knew that Zamora’s religion, like all things of a civilized, long-settled people, was intricate and complex, and had lost most of the pristine essence in a maze of formulas and rituals.

He had squatted for hours in the courtyard of the philosophers, listening to the arguments of theologians and teachers, and come away in a haze of bewilderment, sure of only one thing, and that, that they were all touched in the head.

Barbaric religion, on the other hand, is forthright and manly.

His gods were simple and understandable; Crom was their chief, and he lived on a great mountain, whence he sent forth dooms and death. It was useless to call on Crom, because he was a gloomy, savage god, and he hated weaklings. But he gave a man courage at birth, and the will and might to kill his enemies, which, in the Cimmerian’s mind, was all any god should be expected to do.

An absurd sentiment, and anyone raised in a Christian era knows better, or should. On the other hand, one need not agree with the worldview to admire how well it fits the world to which it belongs, and fits the tale it means to tell.

A world where more was expected of the gods would not be one as savage, wild, spooky, and strange as the Pre-Cataclysmic Age of Conan. The whole point of a ‘noir’ story, a picaresque tale, or a yarn about rogues and evildoers is to see antiheroes beat up villains more savagely than Christian knights allow. It is a vacation from Victorian uprightness the reader wants. Real gods would spoil the fun, even real pagan gods. (No one in history or prehistory ever worshiped a god he thought useless to call upon.)

I cannot show how Howard is the master of prose without quoting him at length. He is more fluid and poetic than the barebones style favored these days, but not so florid as H.P. Lovecraft nor as elevated and wry as Lord Dunsany or Jack Vance. The prose, like Homer, is direct, vivid, manly.

Here are the opening lines. Next time you try to run a Dungeons and Dragons game, try, just try, to establish the mood of danger, riot, and lawless liberty of your tavern setting so quickly and clearly. You will find it is not so easy.

Would be writers take note of which senses are engaged an in which order: sight, sound, smell, and, in the adroit final metaphor, feeling.

TORCHES flared murkily on the revels in the Maul, where the thieves of the east held carnival by night. In the Maul they could carouse and roar as they liked, for honest people shunned the quarters, and watchmen, well paid with stained coins, did not interfere with their sport.

Along the crooked, unpaved streets with their heaps of refuse and sloppy puddles, drunken roisterers staggered, roaring. Steel glinted in the shadows where wolf preyed on wolf, and from the darkness rose the shrill laughter of women, and the sounds of scufflings and strugglings.

Torchlight licked luridly from broken windows and wide-thrown doors, and out of those doors, stale smells of wine and rank sweaty bodies, clamor of drinking-jacks and fists hammered on rough tables, snatches of obscene songs, rushed like a blow in the face.

Howard is also a master of the art of ‘camerawork’ that is, knowing what not to say. This is from later in the same scene:

‘Heathen dog!’ he bellowed. ‘I’ll have your heart for that!’ Steel flashed and the throng surged wildly back out of the way.

In their flight they knocked over the single candle and the den was plunged in darkness, broken by the crash of upset benches, drum of flying feet, shouts, oaths of people tumbling over one another, and a single strident yell of agony that cut the din like a knife.

When a candle was relighted, most of the guests had gone out by doors and broken windows, and the rest huddled behind stacks of wine-kegs and under tables.

The barbarian was gone; the center of the room was deserted except for the gashed body of the Kothian. The Cimmerian, with the unerring instinct of the barbarian, had killed his man in the darkness and confusion.

Howard also can make a minor character, on stage for but half a chapter, spring to life, such as when the Prince of Thieves schools young Conan with sound advice about his trade:

We’ll strangle old Yara before he can cast any of his accursed spells on us. At least we’ll try; it’s the chance of being turned into a spider or a toad, against the wealth and power of the world. All good thieves must know how to take risks.

A writer not only must set the stage and bring the characters to life. He is also the prop-master. Howard creates a world where even ordinary objects are overlaid with dark glamour. As example, here is the tale of an ampule of poisonous powder:

‘Because that was all the powder I possessed. The obtaining of it was a feat which in itself was enough to make me famous among the thieves of the world. I stole it out of a caravan bound for Stygia, and I lifted it, in its cloth-of-gold bag, out of the coils of the great serpent which guarded it, without awaking him. But come, in Bel’s name! Are we to waste the night in discussion?’

Or a climbing rope:

‘It was woven from the tresses of dead women, which I took from their tombs at midnight, and steeped in the deadly wine of the upas tree, to give it strength.’

A writer knows when lure the reader onward with a bit of dark mystery:

Gingerly the barbarian ran his hands over the man’s half-naked body, seeking a wound. But the only marks of violence were between his shoulders, high up near the base of his bull-neck—three small wounds, which looked as if three nails had been driven deep in the flesh and withdrawn. The edges of these wounds were black, and a faint smell as of putrefaction was evident. Poisoned darts? thought Conan—but in that case the missiles should be still in the wounds.

Howard is a master of mood. Some things are just way cool, but one is likely to notice only after reading more of Howard’s world:

‘You are not of Yara’s race of devils,’ sighed the creature. ‘The clean, lean fierceness of the wastelands marks you. I know your people from of old, whom I knew by another name in the long, long ago when another world lifted its jeweled spires to the stars.’

The creature is remembering Atlantis. According to Howard’s background, Conan comes from the same long bloodline as Kull.

Finally, Howard is a master of the genre that he makes his own.

And sometimes you stumble over the threshold of strangeness, and realize you are in a science fiction and not a fantasy world, or perhaps you realize that the two genres are not two at all, but one. Who told you that imagination was different from speculation?

‘I am very old, oh man of the waste countries; long and long ago I came to this planet with others of my world, from the green planet Yag, which circles for ever in the outer fringe of this universe. We swept through space on mighty wings that drove us through the cosmos quicker than light…’

Howard is a master of the craft. Small wonder these stories are the best remembered of all his prodigious output. Looking at the publication dates, I notice the first three Conan yarns appeared in the pages of Weird Tales in four months: December, January, and March.

If you are wondering, the February issue for that year had stories by H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith, so I am sure the readership yearning for weird tales in Weird Tales were not disappointed. It was a golden age.

Why does our own age seem to have so much tin, which corrodes other metals it touches, so much brass, and so little gold? It may be that a gloss of nostalgia brightens some of the old works. But it also could be that modern and postmodern writers are not trying to write golden works.

We have among us these days men who are the opposite of alchemists. They turn gold into base metals.

Here is the secret to why so much modern fantasy fiction is not just bad, but extremely bad, deplorably bad, deliberately bad: modern fantasy on the whole is morally repugnant, intellectually flat, and viscerally disgusting.

Too many modern fabulists are not friends of the Perilous Wood where dangerous shadows dwell, alarming monsters, fair maidens, and sights fabulous and strange. They are foes. They follow not the tradition of fairy stories reaching from Weird Tales to 1001 Arabian Nights, and the Song of Roland to the Odyssey of Homer. They follow the fashionable nonsense of Marx and Nietzsche and Hegel and Hume, who believe that reality is optional, all morals are manmade hence arbitrary, and that life is merely the endless Darwinian struggle between oppressor and oppressed.

The postmodern thought (using the word in a loose sense) holds that reality is merely a story, a narrative, which the strong tell the weak in order to oppress them, and that true enlightenment consists of realizing that there is no truth, hence no story to tell.

Postmodernism holds that there is neither good nor evil, neither high nor low, neither fair nor foul, neither virtue nor vice.

But story-telling consists is telling literal truths in figurative ways: metaphors, similes, images and examples. Even the shallowest boy’s adventure tale contains a soul. The story makes a world, and therefore holds a worldview.

In every worldview, there is something uplifted as high, the peak of what is desired and sought, and something else depressed as low, the pit of what is fled.

In every story, Heaven is high and Hell is low; or, at least, Elysium is above and Hades down below. Every earth is a Middle Earth, for a higher world of aspiration calls the hero up, and an underworld of fear, folly, temptation and horror tempts him to fall.

The nature of the drama, whatever the drama is, consist of the struggle of the main character to climb from pit to peak. In tragic stories, his own flaws make him stumble, and he slides down. In happier stories, he struggles and climbs and finds the peak. He wins the girl, or learns a lesson, or saves the kingdom, and returns home and puts his child on his knee and smiles.

And in tales that are deeper, that is, more truthful, we find that after the struggle, the bruised but unbowed hero stands aloft but is surprised that he ends up with a different victory, atop a different peak, than he saw looking up from below, when he started.

But postmodernism is a worldview that says all worldviews are false. One man’s peak is another man’s valley, therefore there is no innate meaning in life, no gods, no moral law, no Aesop’s lesson to be learned, no victory and no downfall. There is no height, and no depth. There is nothing but a flat and featureless plane, reaching endlessly to no horizon, with no water, no shade, and no directions.

Stories of any genre, even if they copy all the furniture of fantastic tales, told in this worldview have nothing to say, and contain no drama. They are executed like graffiti, merely to mar what other, more skilled hands, have put in place.

Now, a well-crafted tale, on the other hand, even if it holds a worldview not to the reader’s taste or liking, the reader will like and admire (and, if that reader is as I am, will adore) any tale whose worldview is not flat and meaningless. A pagan tale of what a pagan calls high and low I may think to reflect a worldview that is only half the truth, but that half is half I can love, if the teller of the tale knows his business.

And Howard knows.

Story speaks. Hello, Story. We’ve missed you.

Excellent insights. Yes, plotting, writing skill, and characterization are vital, but a distinct and coherent moral core drives the best fiction. It’s the engine that makes a memorable ride possible.

@well paid with stained coins- Howard sure knew purple passages. My memory tells me Poul Anderson used that opening scene over and over in all kinds of stories, but Memory, hold the door for pleasurable rereading.

This is a story so good it deserves to be a “Trope”…

“Well, my Tower of the Elephant was when Damian found the mad monk in the Relical…”

For an alien environment revealing enough to spark the imagination without a ton of this, that, etc.

But whoop – modern “Fantasy” which is bloated (hey, a penny a word ain’t what it was) and with paper thin plots – well the ‘backstory’ is part of the huge block of text to get TO any semblance of a story…

Awesome article!

This is my favourite Conan story for a reason, and this posting explains why.

>Why does our own age seem to have so much tin, which corrodes other metals it touches, so much brass, and so little gold?

Mr Wright, we are obviously on the same wavelength, as I looked at a similar issue on my blog recently using a very similar metaphor.

Regards.

Another awesome post! Can’t get enough of these articles. Thanks!

I love this one. Probably my favorite Conan story, too.

It’s fitting that Mr. Wright brings up Lovecraft. “The Tower of the Elephant” is part of the Cthulhu mythos.

Also, this is my favorite Howard story as well.

I had forgotten that this yarn was part of the Cthulhu Mythos. I don’t know if this is my favorite Conan story, but I do know that this is the story that I recommend someone new to Conan should read first.

Now I know why. Thank you, Mr. Wright.