Defending Ambiguity Against the Cannons of the Brave New World

Tuesday , 30, December 2014 Uncategorized 14 Comments

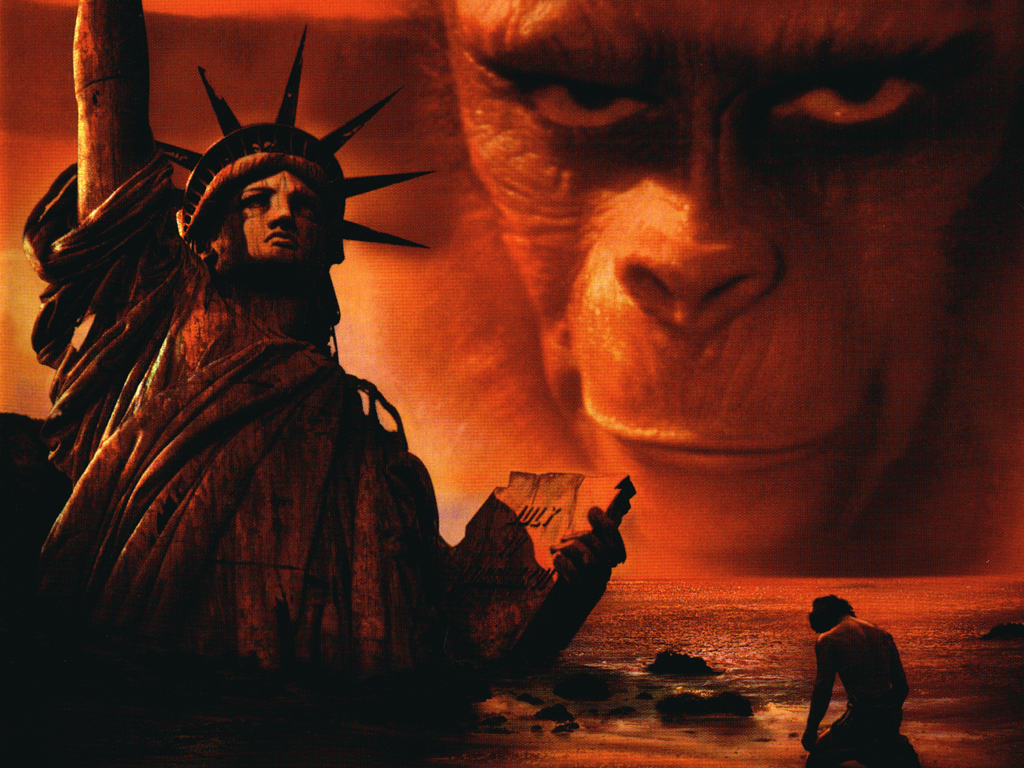

Ambiguity is a delicate art. Done well, it points the mind toward ideal forms. That’s why, when it goes wrong (Monkey Lincoln Memorial) it burns the Bridge to the Beyond.

A cartoon that I know absolutely nothing about has come under fire from its fanbase for tacking on a Pink SF message to the series finale.

Of course, the usual media advocates of the Brave New World don’t even bother with a fig leaf of objectivity in their reportage:

So let’s continue to celebrate both Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra for doing so much to challenge expectations and bravely explore content outside the scope of children’s television. In the parlance of the shipping world, Korrasami is canon. And to bend that word slightly, that cannon is firing in celebration of a brave new world. Thanks to Bryan, thanks to Mike, and thanks to the entire Team Avatar.

Now, a moral judgment can easily be made on this matter, but I’ll leave that to one of the show’s former fans to justifiably take to his high horse, and level his curative lance at the target in that particular arena.

No, what I’m interested in is the remarkable tendency of SF authors and creators to cut the heart out of their own stories. I don’t need to know anything about the Legend of Korra to recognize that when its creator says this:

Our intention with the last scene was to make it as clear as possible that yes, Korra and Asami have romantic feelings for each other. The moment where they enter the spirit portal symbolizes their evolution from being friends to being a couple. Many news outlets, bloggers, and fans picked up on this and didn’t find it ambiguous.

He’s not only lying, but he’s discrediting one of the most important elements of Science Fiction:

Ambiguity.

Now the lie (that the ending is so obvious and unambiguous that he doesn’t need to comment on it) can, like most lies, be overcome or ignored. Athletes and celebrities “apologize” for crimes over which they feel no remorse all the time. The public politely tends to note the lie and conducts a ritual of “accepting” the apology anyway. Its the fastest way to make the charade go away, after all.

If the lie lays the blade against the throat of the cartoon’s art, however, it is the creator’s strike against ambiguity itself, and that strike alone which slays his own cartoon and burns the corpse.

Proper care and attention to a tale’s ambiguity is critical to the successful completion of any speculative story. Allow me to prove this:

Ambiguity – uncertainty or inexactness of meaning in language – has its origins in the concept of doubt. If the definition of “faith” is a confidence in something unseen, then ambiguity is an uncertainty – a lack of confidence – in that unseen thing. In other words, the thing itself (and this can be anything unseen) is not in doubt – but the observer’s faith in that thing is weak or even non-existent. Ambiguity is about the observer: the viewer of the cartoon, or the reader of the novel.

This tool–this experience of ambiguity–is critical to Blue SF.

“If you want to send a message, use Western Union.” – Sam Goldwyn? (maybe. I actually didn’t look this quote up. In the spirit of Ambiguity, of course…)

People listen to sermons for much different reasons than they read SF, and if a reader wants a message, he’ll read a sermon or propaganda or instructions. But the one thing that unifies nearly all readers of Blue SF is that they want a story, and while that story may have a moral, or a theme, or a general cohesive (if vague) approach, what it won’t have is a message.

Take a few classic examples: since the subject is children’s entertainment, The Giver, by Lois Lowry is a tale of a child-to-man’s heroism and sacrifice in the face of a dystopic culture. It has an ending that wins accolades from library associations and public educators, primarily because they are incapable of processing ambiguity. A lot of books that pass through the gates of public child-minders have certain qualities: the unnecessary death of someone good being chief among them. The funny thing about The Giver is that its ending really and truly is left an open question, as Lowry herself did not intend, or interpret, the ending that many – if not most – of her readers did! She simply wrote the ending of the book, artfully and ambiguously, because that is what the story called for.

In adult fiction, Philip K. Dick is a master of ambiguity, even when – actually especially when – he has a specific idea about a character’s state (i.e. whether they are a human or a computer construct, for example.)

Books can be partially or fully ruined when an author makes declarative statements about elements from their works that are artfully left ambiguous (or sometimes totally absent): Rowling making a dramatic statement about Dumbledore being certainly gay, as if that had provided the kernel for his character choices or something.

It isn’t just in endings: read just about any Jack Vance novel, and you are likely to find yourself wondering–at least at some point–whether or not you actually want the main character to succeed in his efforts. It is that ambiguity that drives the narrative forward in many key spots.

Ambiguity is the X on a treasure map – Not the treasure itself, but without the X, you’ll never find anything…

Ambiguity in time travel. Ambiguity in outer space. Unknowns and doubts and uncertainty principles are not the only stuff of Blue SF, but they are most definitely among the necessary stuff of Blue SF.

Of course there are unintended ambiguities – writerly ones – that any creator should try to avoid.

The real ones? The right ones?

It is the task of the creator to identify them, and defend them to the death.

Ambiguity is in most cases the only way for a mortal writer to identify the X that marks the ideal form for which any good Blue SF story is its map.

The Brave New World has cannons, and their target is blasting Ambiguity off the map.

That alone should be reason enough to rush to such a treasure’s defense.

Ambiguity makes the best propaganda. You’d think propagandists would understand that.

-

Except that they are not interested in capturing the mind or the heart, which is something that effective propaganda does. They only want to give instructions for thought, and the illusion of feeling, to those who are already beholden to their tacky ideology.

The soft Marxists bothered with propaganda back when the Baby Boomers were relevant: Left Hand of Darkness, Easy Rider, popularized slogans (“Make Love Not War”), John Lennon, etc. and they sought propaganda opportunities to build off–not directly modify– culturally recognized stories, too (“Frodo Lives!”, the Jesus People, etc.)

Today they are not the Great and Powerful Oz, but just a tired old charlatan exposed, and every pronouncement and work of art is – in essence – some jerk fumbling about, screaming, “Pay no attention to the cis-man behind the curtain!”

The only ones who might even bother listening are those who already have a vested interest in everyone else being miraculously struck back into line.

Oh, the irony of using the phrase “brave new world” in a positive context.

-

Yes, it was very silly of Shakespeare, wasn’t it?

-

Irene, Shakespeare used to express Miranda’s naivete. It was not originally positive, but demonstrative of enthusiasm for innocuous-seeming treachery.

That’s why Huxley used it for his book. It’s like when a girl looks at a blood-sucking vampire and says, “Oooh! Sparkly!”

-

Jonas from “The Giver” actually appears as a character in one of “The Giver’s” sequels (which are quite good, by the way).

-

Yes, that is what I was alluding to. I think the Giver gets a pass now out of tradition, but it got through the gate because the gatekeepers thought it was a “Bridge to Terabithia” materialist downbeat ending.

It is actually quite triumphant, and I recommend the entire series for kids about twelve years old or so.

-

The interpretation that Jonas died is a fairly valid one, if the book is taken on its own. But it’s not on its own – it’s part of a very well-written series.

Lowry is a very good author. “The Giver” is basically a children’s version of “Brave New World”.

-

Oh it was my interpretation, too! But it wasn’t a meaningless “death” – the important thing was that he risked everything for the Good, and he did it like a man. The Ambiguity in the Giver is not only proven in the later books, but it confirms what I think is the essence of the tool: had the Giver clearly and unambiguosly slain Jonas, and had the author posted messages like “He’s dead, really and truly…” that would have taken the strength out of the book.

I believed he was dead. I would not have had my understanding for the story taken away had Lowry been unambiguous. But I would have had the essence of the spirit of the story negated.

It is a subtlety entirely lost on the BNW SJWs dead set against Hope and Faith, the necessary gifts exercised in the face of well-done Ambiguity.

-

-

Not to unambiguize the ambiguity of your post, but the Western Union quote is an old movie adage, first put into print by screenwriter William Goldman in his book “Adventures in the Screen Trade”.

Tolkien would concur with you in regards to ambiguity:

“As a story, I think it is good that there should be a lot of things unexplained (especially if an

explanation actually exists); and I have perhaps from this point of view erred in trying to explain

too much, and give too much past history. Many readers have, for instance, rather stuck at the

Council of Elrond. And even in a mythical Age there must be some enigmas, as there always are.

Tom Bombadil is one (intentionally).”

-Letter 144, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

The more authentic and rich a story becomes, the more life it will contain, and the more life a work has the more difficult it will be to reduce it to any one central message, the One meaning to rule them all. To reading Lord of the Rings as an allegory about atomic power requires one to to squint, smudge out the details, and strip the story of its vitality.

-

Thanks! I really had no idea. I usually take care about misattributed quotes, but I thought it was funny. Or at least meta-humorous. Or lazy. You pick.

The final scene showed Korra and Asami clasp both each other’s hands and stare adoringly into one another’s eyes. It may have been a mistake to assume the intention was obvious (and really, the scene is as clear as a kid’s network would allow) but it was no lie.

-

No, he’s lying that it didn’t need explanation. If it didn’t need explanation…why on earth is he explaining it?

The honest artistic response would have been either to say: “It was possibly unclear, so let me explain it” OR “It was perfectly clear. Simply watch the show.”

The dishonest, incoherent response is “It was perfectly clear, so let me explain it so that it is perfectly clear.”

Unnecessary lies like this have NO PLACE in art. The liar does it because he receives the benefit of appearing like an artist (who doesn’t have to explain himself) AND a social educator (who gets to explain himself.)

In art, this is a cheat and a lie. The artist may clarify his intentions. He may leave his intentions in the hands of the viewer.

He doesn’t get to control the clarity and the interpretation simultaneously.

That’s propaganda.