Defining Fantasy Role-Playing Games the Tunnels & Trolls Way

Thursday , 4, August 2016 Appendix N, Tabletop Games 12 Comments Gamers are a tough crowd in general, but role-players are particularly hard to get along with. The number of shibboleths and sacred cows in the rpg scene, the emperors with no clothes, the punditry and smack talk, the number of ways to give and take offense, the outright character assassination and demagoguery that goes down– not to mention the tribalism and uneasy alliances, gang wars, turf wars, and the all around cantankerousness of the average nit picker– I’m telling you, role-playing games are among the hottest of hot potatoes.

Gamers are a tough crowd in general, but role-players are particularly hard to get along with. The number of shibboleths and sacred cows in the rpg scene, the emperors with no clothes, the punditry and smack talk, the number of ways to give and take offense, the outright character assassination and demagoguery that goes down– not to mention the tribalism and uneasy alliances, gang wars, turf wars, and the all around cantankerousness of the average nit picker– I’m telling you, role-playing games are among the hottest of hot potatoes.

Why’s it like this? Well, it’s complicated. A big part of it a lot of people are talking about completely different things when they use the term “role-playing game”, and even people making a good faith effort to get along are unable to come to a consensus on how to define the darn things. (And really, people. Don’t even try to drag computers into this. That way lies madness…!)

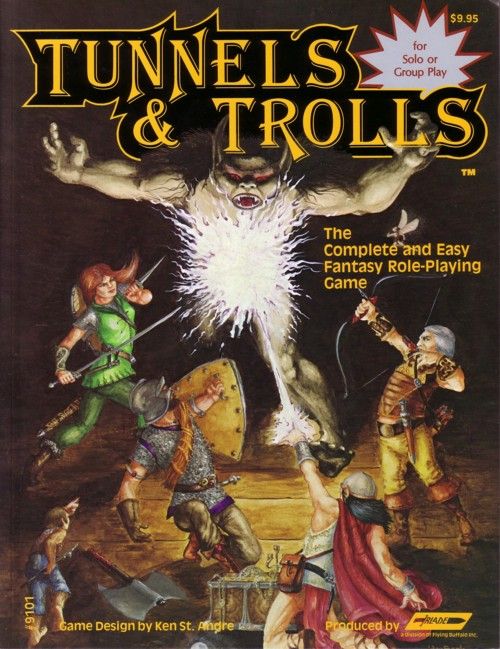

The only way to dig through this mess is to return to the elements and the foundations of the genre. Oh sure, time marches on, fads come and go, and there are new developments in gaming all the time. But I personally don’t see how it helps to stretch and twist and abuse and mold and tweak a perfectly good term until it ceases to correspond to anything. So lets go back to 1979 and take a look at the back cover of 5th edition Tunnels & Trolls to see how things were framed back then.

A fantasy role-playing game is one in which the players (sometimes one, often several) can assume the personas and personalities of imaginary beings– not always human– who are thus given lives and adventures of their own, directed by the game players.

Now note that if you just stop right there, everything from Pac-Man to Wolfenstein 3D suddenly becomes an rpg. So don’t stop reading! Because while this idea of playing a role is certainly a necessary element of rpgs, it is not sufficient in and of itself.

In the course of the game, characters (the imaginary ones) are presented with circumstances created in outline by a Game Master. The fulfillment of that outline depends upon verbal give-and-take between the Game Master and the players as they explore the world presented, taking actions to cope with the situations in which they find themselves.

That’s right. A Game Master is integral to the definition of role-playing games. If there’s no human referee sorting things out with the players in a “verbal give-and-take”, then it’s not a role-playing game. By this standard, Crowther and Woods, Scott Adams, and Infocom came the closest to bringing role-playing games to the computer format of anyone. If you think things like attribute checks, saving throws, skill ratings, character classes, and to-hit rolls were in any way central to the concept, then you’re basically lost here.

The Game Master is a real person who has taken the time to create the scenario in scenarios in which his or her friends can play. The players may be using medieval knights, space-faring aliens, or a cowpuncher from the Old West.

Yep. The Game Master has to be a real person and not a book, a board game, a flow chart, or a computer program. And before you get your panties in a wad over that, check out how the term “fantasy” no longer means what it did back in 1979. There weren’t hard and fast boundaries between the genres back then and fantasy was broad, deep, and diverse.

Tunnels & Trolls is designed primarily as a fantasy role-playing game set in a somewhat medieval alternate-universe, in the tradition of the hero tales of Greece and Rome, the Norse sagas and the Eddas, childhood fairy-tales, and in the more modern traditions of the heroic fantasy of JRR Tolkien and Robert E. Howard.

Again, the term “fantasy” as it is used here is broad, deep, and diverse. It is rich and varied, not derivative. It has roots and is not merely a style, a formula, or a marketing category.

The fundamental framework for adventuring in Tunnels & Trolls is the concept of an underground tunnel complex wherein dangerous traps and deadly monsters guard undreamed-of treasures, where magic and high sorcery meet sword and shield, in alliance or as violent opponents. Those who survive to regain the surface may be considered “winners”– until the next time they venture into the depths, risking their all for glory, gold, and adventure.

Now, I’ll admit that this passage has left the general idea of defining role-playing games and moved on to explain the premise of a particular role-playing game. Nevertheless, I think this sheds light on some things that are nearly forgotten or frequently misunderstood today. Notice there is nothing remotely like a story or even a setting here– not like has become the norm today, anyway. There is simply some sort of insane funhouse that people run their characters into for no other reason than that it’s fun. The chance of death is fairly likely. The chance of striking it rich is far from certain, but well within the realm of possibility. The “glory” thing is key, though: the totally unexpected thing that emerges from the chaos and randomness and arbitrary decisions but which nevertheless makes perfect sense and which is better than anything that anyone could have planned…? That’s why these games took off like they did. No other type of game brings that to the table!

No, I’m not saying that awesome things don’t happen when people play board games and computer games and wargames. But this particular alchemy I’m talking about here, I think it’s bound up with all of this: with people playing roles, pursuing an arbitrary and easily understood goal, steadily pushing their luck in the context of an increasingly deadly environment– and all of that filtered through the verbal “give and take between the referee and the players” in a kitchen sink fantasy environment where every myth or pulp story is fair game.

The definition of role-playing games may be hard for people to agree on, but it’s all of these elements together that reliably produce the things that are most interesting about them.

I’ve pondered this myself in recent days. As you point out, pretty much any game can be considered an RPG if all that’s required is placing the player in the role of an in-game character.

For all practical purposes, I think video game RPGs need to be included under the umbrella (unless your interest, niche, or fanbase/readership exclude them). You’re right that they have to be shoehorned in when you actually consider the definition and original design of role-playing games, but I think it’s more a matter of practicality.

Sure, we could say that games like the Final Fantasies are not really RPGs. But to craft a new term and gain threshold acceptance and usage of the new language seems a herculean effort.

The problem with calling computer games RPGs is that the players are limited to those actions that are pre-programmed into the game.

The sheaf of potential actions may be very large, but it is still limited. No player in a computer game is able to do something that the designers of the game did not anticipate.

Now, some combinations of items and actions may have consequences that the designers did not expect, but the mechanism by which things are done is perforce selecting from a limited number of options.

Any computer game is reducible (in theory) to a decision grid. Given sufficient time, any computer game can be beaten by a brute force numerical approach. You could write a program to provide the input that a human player would provide and run through every combination of “AAAAAAAA” “AAAAAAAB” “AAAAAAC” and so on. Eventually–completely without any comprehension of the game, just by running through every possibility–such a program could beat any computer game.

Role Playing Games, on the other hand, are a dialogue between GM and players, and as such are unlimited in scope.

To give an example, let’s take the classic tavern brawl scenario. In a computer game the programming team must create all the elements of the tavern in advance and determine how each element will function. You can pick up a chair and use it as a weapon only if the programmers set the chair elements up that way when they designed that level.

On the other hand, a live GM can react to the players on the fly and make a ruling about the suitability of furniture as improvised weapons at the moment the player decides to use it.

In a computer game a character who has a magic gem is limited to, say, “use item”, “drop item”, or “sell item”. A character may want to swallow the gem to keep it from being stolen, but that can only happen if the development team made “swallow item” as an option. A live GM could allow it or not based on her or his spur of the moment decision on that actions practicality.

-

You all are presenting perfectly reasonable points. My point is merely that the language has evolved in a sadly inefficient way. Present company and related circles have no difficulty following a conversation about “CRPGs.”

However as a pretty recent newcomer to the OSR/tabletop gaming online community, I have to admit I had never heard the term or differentiation before. That’s not to say it’s imprecise or even undesirable. But there are many other corners of nerdery, perhaps most importantly videogamers, who would no doubt be somewhat confused, and most likely resist such a change in terminology.

I guess this is my roundabout, trolly way of saying we can call it whatever we want within our community, but “RPG” has become so ingrained in other parts of nerd culture and so strongly associated with those games, good luck getting anyone else to accept and use the new terms. Even though they’re wrong. 😉

-

Yeah, I can see how people used to talking about Computer Role Playing Games would continue to use that term, just like people who talk about Computer Sports Games would continue to use that term. But someone playing a computer game is no more engaging in role playing than a person playing a computer game is really playing hockey.

-

In my circle, at least, what’s happening is that real RPGs are increasingly called Tabletop RPGs (I haven’t so much seen TRPG, but the abbreviation is probably out there). This is annoying to the historically-minded pedant in me, but does have the virtue of clarity.

-

As a DM, I quickly found the idea that the adventure “has to be underground” too limiting. I created plenty of outdoor adventures and urban adventures. My players eventually rose to command armies in the field so I had to incorporate rules for large-scale combat.

That side, I have fond memories of playing T&T!

CRPGs are far more in line with what are called “Visual Novels” than tabletop RPGs; analyzing them within that context would be a wonderful starting point if “serious” CRPG gamers weren’t potentially offended at the prospect of their games being lumped in with dating sims.

But given the similarities (limited interactivity with the end goal of witnessing a story while being a semi-active participant in it from a 1st person role perspective with the intention of going through the necessary motions of seeing the story’s conclusion), they’re totes the same thing. True Love was a CRPG where you min-max stats to impress girls while Xenogears is a 60 hour visual novel with combat, skill and levelling systems stapled onto it.