It was a simpler time…

One quality I love about pulps and classic science fiction works is how much physical confrontation is in them. Whether it involves mech suits, killer drones, shooting, swords, fisticuffs, or wrestling, there was heaps of full-blooded action. And it’s seemingly simple, right? Just write about one man punching another! How hard that can be?

And yet, as with many writing skills that critics thumb their noses at, it’s a rare author who can do it effectively! What can we learn from the old masters, and what pitfalls should we avoid? Let’s look at a few different approaches;

Detailed Description-

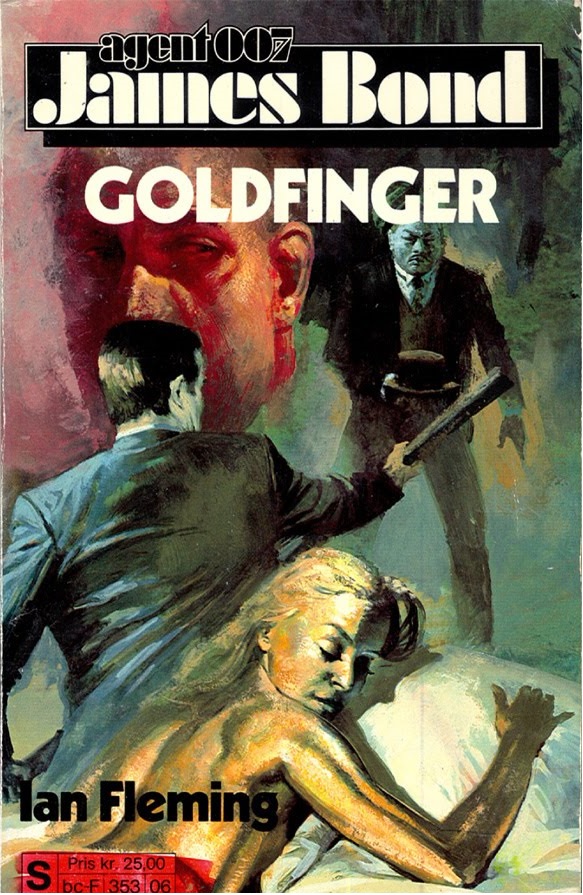

Typically, this means specific listing of everything involved in the action scene, from the movements themselves to the surroundings to the state of the combatants. The author will describe the arc of the punch, how his right foot is positioned, the sweat greasing the fighter’s brow, the fluorescent light shining in his eyes, and many other details. Even a short, single encounter can be described over multiple pages. An example of this style is present in Ian Fleming’s James Bond series. Here is a part, not even the whole passage, of an unimportant fight Bond engages in with an unnamed Mexican gangster at the beginning of Goldfinger;

The gesture of the hand slipping into the coat was so well known to Bond, so full of old dangers, that, when the hand flashed out and the long silver finger went for his throat, Bond was on balance and ready for it.

Almost automatically, Bond went into the ‘Parry Defence against Underhand Thrust’ out of the book. His right arm cut across, his body swivelling with it. The two forearms met mid-way between the two bodies, banging the Mexican’s knife arm off target and opening his guard for a crashing short-arm chin jab with Bond’s left. Bond’s stiff, locked wrist had not travelled far, perhaps two feet, but the heel of his palm, with fingers spread for rigidity, had come up and under the man’s chin with terrific force. The blow almost lifted the man off the sidewalk. Perhaps it had been that blow that had killed the Mexican, broken his neck, but as he staggered back on his way to the ground, Bond had drawn back his right hand and slashed sideways at the taut, offered throat. It was the deadly hand-edge blow to the Adam’s apple, delivered with the fingers locked into a blade, that had been the stand-by of the Commandos. If the Mexican was still alive, he was certainly dead before he hit the ground.

Bond stood for a moment, his chest heaving, and looked at the crumpled pile of cheap clothes flung down in the dust. He glanced up and down the street. There was no one. Some cars passed. Others had perhaps passed during the fight, but it had been in the shadows. Bond knelt down beside the body. There was no pulse. Already the eyes that had been so bright with marihuana were glazing. The house in which the Mexican had lived was empty. The tenant had left.

Again, keep in mind that this isn’t the entirety of the description, and is part of a flashback at the beginning, before the story truly begins! Now, I’ve read all of the Ian Fleming Bond books, and consider them enjoyable enough, but nothing special. That also applies to the fight scenes. The one above is serviceable and has a pleasing, poetic conclusion, but several details actively hinder a reader conjuring up the scene in his head, instead of aiding him. For instance, what the hell is a “crashing short-arm chin jab” and what does it look like? I was an amateur boxer and have never heard of such a strike! Right off the bat, the book’s description collides with my own mental vision of what Bond’s punch looks like after he stopped the knife thrust.

Again, keep in mind that this isn’t the entirety of the description, and is part of a flashback at the beginning, before the story truly begins! Now, I’ve read all of the Ian Fleming Bond books, and consider them enjoyable enough, but nothing special. That also applies to the fight scenes. The one above is serviceable and has a pleasing, poetic conclusion, but several details actively hinder a reader conjuring up the scene in his head, instead of aiding him. For instance, what the hell is a “crashing short-arm chin jab” and what does it look like? I was an amateur boxer and have never heard of such a strike! Right off the bat, the book’s description collides with my own mental vision of what Bond’s punch looks like after he stopped the knife thrust.

And that’s generally true of this approach. It can work for the right author, and the success of the Bond books is testament to that, but there is always the danger that over-describing will conflict with the reader’s own picture of the events. To use a painting analogy, there are too many brushstrokes, and it’s easy to get one wrong, as with the “crashing short-arm chin jab”.

More Focused Description-

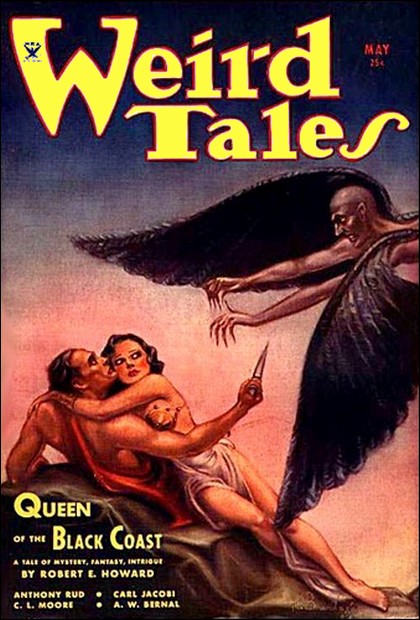

Instead of describing everything, the author chooses to hone in on several particular features of the struggle. Fights can still be long, and there is plenty of detail on the key elements, but not all aspects of the fight are given attention. Consider, for instance, a portion of the combat in Howard’s Queen of the Black Coast;

Then something swept down across the stars and struck the sword near him. Twisting about, he saw it—the winged one!

With fearful speed it was rushing upon him, and in that instant Conan had only a confused impression of a gigantic man-like shape hurtling along on bowed and stunted legs; of huge hairy arms outstretching misshapen black-nailed paws; of a malformed head, in whose broad face the only features recognizable as such were a pair of blood-red eyes. It was a thing neither man, beast, nor devil, imbued with characteristics subhuman as well as characteristics superhuman.

But Conan had no time for conscious consecutive thought. He threw himself toward his fallen sword, and his clawing fingers missed it by inches. Desperately he grasped the shard which pinned his legs, and the veins swelled in his temples as he strove to thrust it off him. It gave slowly, but he knew that before he could free himself the monster would be upon him, and he knew that those black-taloned hands were death.

The headlong rush of the winged one had not wavered. It towered over the prostrate Cimmerian like a black shadow, arms thrown wide—a glimmer of white flashed between it and its victim.

Notice that the way in which Conan grasps for his sword, or the manner in which the winged one rushes towards Conan is described simply, and left up to the reader’s imagination. However, the physical characteristics of the antagonist, as well as the desperate, panicked nature of the situation are made abundantly clear to the reader. This particular battle is picturesque and poetic, and is a good example of why I like the approach. Those important details that the reader might not be able to imagine himself are given plenty of brush strokes, but the rest is done more minimally, as one can handle it without the author’s intercession. Of course, that doesn’t mean that merely adopting this style will yield instant success. One still has to know what is important in painting the scene and what isn’t, and be skilled in describing the former!

Notice that the way in which Conan grasps for his sword, or the manner in which the winged one rushes towards Conan is described simply, and left up to the reader’s imagination. However, the physical characteristics of the antagonist, as well as the desperate, panicked nature of the situation are made abundantly clear to the reader. This particular battle is picturesque and poetic, and is a good example of why I like the approach. Those important details that the reader might not be able to imagine himself are given plenty of brush strokes, but the rest is done more minimally, as one can handle it without the author’s intercession. Of course, that doesn’t mean that merely adopting this style will yield instant success. One still has to know what is important in painting the scene and what isn’t, and be skilled in describing the former!

Terse Description-

Here, the author will only describe the minimal amount to convey the scene. Nothing more. Here, for instance, are three different action scenes from Philip Jose Farmer’s Rastignac the Devil;

- As they left, Rastignac saw a cloaked figure slinking from the back door of the Ministry. Seized with intuition, he tackled the figure. It was an Amphib-changeling. Rastignac struck the Amphib with a venomous arrow before the Water-human could cry out or stab back. Mapfarity grabbed up the limp Amphib and they raced for the safety of the castle.

- Within a minute the square had erupted into a fighting mob. Staggering, red-eyed, slur-tongued, their long-repressed hostility against each other, released by the liquor which their bodies were unaccustomed to, Human, Ssassaror and Amphib fell to with the utmost will, slashing, slugging, fighting with everything they had.

- They began unloading the chests while Rastignac kept an eye on Lusine. He saw her run up, stop, say a few words to the Amphib King, then kneel and stab him, burying the knife in his jugular vein. Then, before anybody could stop her she had applied her mouth to the cut in his neck. The Human-King kicked her in the ribs and sent her rolling down the steps. Rastignac saw correctly that it was not her murderous deed that caused his reaction. It was because she had dared to commit it without his permission and had also drunk the royal blood first.

This might seem like it’s not nearly enough brush strokes. And yet, the story is thrilling and full of adventure! These short, violent scenes are plentiful, and each does just enough to allow one to picture what is going on. They are not poetic, but they are fun and action-packed, especially within the context of the rest of the tale. While it worked for Farmer and a few others, I consider this a very challenging style. It’s so easy to have one’s description end up drab and lifeless. It takes a great author to build the proper story around these scenes and maximize the minimalist description to create an exciting, vivid vision for the reader.

This might seem like it’s not nearly enough brush strokes. And yet, the story is thrilling and full of adventure! These short, violent scenes are plentiful, and each does just enough to allow one to picture what is going on. They are not poetic, but they are fun and action-packed, especially within the context of the rest of the tale. While it worked for Farmer and a few others, I consider this a very challenging style. It’s so easy to have one’s description end up drab and lifeless. It takes a great author to build the proper story around these scenes and maximize the minimalist description to create an exciting, vivid vision for the reader.

Description Reminiscent of a Hollywood Movie or Video Game-

This is a common pitfall for many newer works, and one I’ve mentioned before in my columns. Reading the scene, it’s ripped wholesale from a generic Hollywood CGI blockbuster or a popular first-person shooter. There is no imagination, just the same scene millions have seen on a screen. Not only is this dull and uninspiring, it always makes me wonder why I’m bothering reading this instead of playing the game or watching the movie, instead? I read books for something different and unique, not a watered-down version of what other mediums are offering. Avoid this, regardless of one’s style of description!

NOBODY wrote — or writes — fight scenes better than Howard. Quite a few have come close, though. REH was an amateur boxer himself, had a small sword collection and talked to plenty of veterans and cowboy old-timers. He also spent his youth growing up in a violent boomtown. It didn’t hurt that he was a fan of good “fight sceners” like Haggard, Burroughs, Lamb and Merritt.

In the end, though, his ability to put HIMSELF wholeheartedly into a scene along with his considerable poetic talents would appear to be the deciding factor.

One of the things a writer can do to improve his fight writing is grab a free digital copy of one of the old Boxing Story pulp magazines and read it cover to cover. You’ll get a variety of authors describing fights in a variety of ways – everything from campy to detailed to vague poetry. As with most of the 30s and 40s pulps, the rest of the stories hold up really well, too. I noticed that redemptions is a huge theme among the boxing pulps, because it provides a great human touch and an easy buy in for the reader to root for the protagonist.

You mean “Home in on”, not “hone in”.

Vlad, can you give a particularly egregious example of a “video game”-style fight scene?

As a reader, I find fight scenes (especially of the battle variety) to often be confusing. They’re rarely done in a way that doesn’t appear a muddle in my head.

Going by the samples you’ve given here, it seems that writers fall into two broad camps: A) Those who know something about fighting, and B) Those who don’t.

The writers in the A camp (such as Mr. Howard) seem much more capable of communicating the ‘gist’ of a fight, regardless of their genre or writing style.

Those in the B camp appear to (over)compensate in two ways. Either they’re -way- too descriptive about what’s going on, or they’re terse in the extreme. The second strategy isn’t so bad (such as in Mr. Farmer’s scenes, if the reader doesn’t mind quick fights). The first strategy, however, runs the risk of being unbelievable (the classic example is “punching someone in the balls” — it sounds good on paper, but doesn’t actually work). Extremely detailed but unrealistic fights would certainly be entertaining for readers who didn’t know anything about fighting either, but for those who did…it tends to ruin the illusion. The Goldfinger excerpt above, for example, while exciting, breaks the bounds of credibility. However, if the author isn’t aiming for complete believability (since James Bond is practically a superhero), it may not always matter.

I guess what I’m saying is, if you want to write good fight scenes, either learn how to fake it well, or get in a couple of fights first!

I was just talking about using description as a way of pacing the action over on G+, and I think that’s particularly important in fight scenes.

As a reader (one who has been in a few fights, but has no formal training) all I really want to know is:

Is the hero in danger?

Does he win?

Once you’ve established those things, the level of detail is dependant on how the fight fits in the flow of the narrative.

Generally, I think action scenes should be snappy, with short simple sentences and a minimum of description, but sometimes you want to slow the pace in order to build tension.