Some stories are just so good, you want people to be able to read them without any preconceived notions of what they are about or why they are noteworthy. Here are several of that sort:

Some stories are just so good, you want people to be able to read them without any preconceived notions of what they are about or why they are noteworthy. Here are several of that sort:

- “The True History of the Hare and the Tortoise” by Lord Dunsany

- “Memory” by H. P. Lovecraft

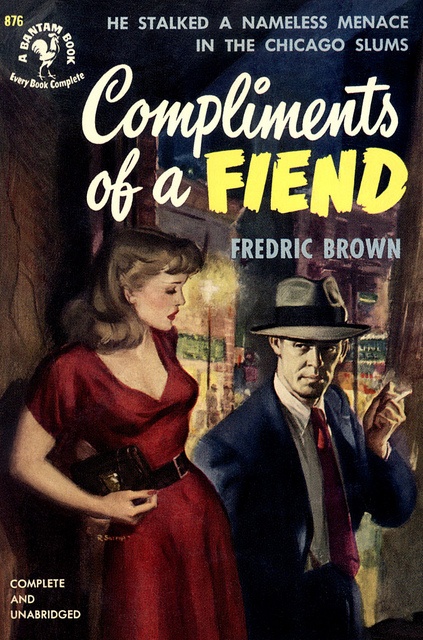

- “Nightmare In Yellow” by Fredric Brown

- Sudden Rescue by Jon Mollison

- “In the Gloaming O My Darling” by Misha Burnett

Now, as I type that out I can already hear the objection: something to the effect that it’s not fair to compare contemporary works to classic authors. The idea is that only the best of the best of the old works survive. People generalize about the past on the basis of this very small sample. You’re comparing the best of the best to contempory works that are effectively singled out at random. People supposedly can’t look at an author and determine anything important about him that people will be talking about two hundred years from now. These aren’t really arguments. They’re a posture. And the subtext of this pretty well boils down to an elaborate variation of “shut up.”

The truth is that effective writing is striking. It stands out. It’s so obvious that children can identify it with confidence. In fact, the classics I list above are ones that my children particularly enjoyed along with me. This is not an accident. Fake masterworks always require the validation of some sort of brilliant commentator who may or may not exist yet. Real master pieces can be enjoyed by practically anyone.

On the subject of misdirection and writing, this tends to come up in the context of crime and suspense stories. I think this is an error, but then… I don’t read crime and suspense stories so much. I would argue that misdirection is a central facet of great writing regardless of genre.

Now, at one end… you can see story construction as being similar to a joke or a magic trick. You are swept along a series of connected events and everything hangs together. You get to the end and you not only get a resolution, but you get some sort consciousness expanding “aha” effect. Sometimes it’s funny. Sometimes it’s chilling. Either way, you have to feed the reader a sense of what the baseline is while mixing in just enough cognitive dissonance to set up the punch line. The reader will think he knows where you are going with things… but then at the end, there is this jerk as he pops from one frame to the other.

Thus everything in the story has to fit with two differing systems of axioms. But the only the second set of axioms fit all of the details. And it is that fit that makes the whole so satisfying.

If you ever notice something along the lines of a “Chekov’s Gun”, then you know the spell has not been successfully cast. In David Brin’s first book Sundiver, there is sort of a brain dump at some point. I get to it and I think, “why is he even talking about this stuff?!” And then I get to the end and I realize that he had to tell me that stuff so that I would understand what was happening at the ending.

I get that same feeling frequently when I watch movies. It’s like Bill Cosby’s classic set up for (I think) his Fat Albert story: “Now… I told you that one so I could tell you this one.” That got a laugh in his stand-up routine. If people notice you doing that when you’re telling a story, then you are failing to successfully misdirect your audience. You’re like a magician doing a trick and instead of wowing the twelve-year-old on the front row, you instead draw attention to the dime store gimmick that makes what you’re doing possible.

It’s bad form.

The ultimate contempt that can be shown to the reader is to intentionally not even try. Three examples here: Philip K. Dick’s The Man in High Castle, the “Lost” television show, and the BBC series “Sherlock”. Now, I know the Dick novel has some compelling world building, interesting situations, and so forth. But it reads as if the subject of each chapter was determined by casting the I-Ching. It doesn’t go anywhere; it doesn’t hang together any better than the plots of television shows that are put together by committees of people that simply do not care.

Storytellers can create powerful illusions. And it’s true, they often boil down to little more than the imaginary equivalent of props and sets and stages. But there is a great difference between pulling off a trick and making the audience the butt of a joke. That is the difference between the master and the hack whether you are talking about stories published a hundred years ago or stories published today.

Note: the Fredric Brown story I wanted to call out here was the one where the guy planned out the murder of his wife to coincide with their anniversary. I couldn’t recall the title, though.

Also: I had to ask my son the name of Lovecraft’s best story of all time. He’s explaining to me again why “Memory” is the best. “I’ve read entire novels that don’t even do that.”

Will Murray, in his introduction to the Diamandstone pulp stories, pointed out that many of the most successful writers in pulp’s heyday were amateur (and even professional) stage magicians. Which explains why they were able to use misdirection so well…

Are you referring to the hideous abomination that was the Sherlock Christmas special? Because you cannot be more right.

The Man in the High Castle is one of my favorite books. A wrote a blog post about why, which oddly, someone here responded to. That was a long time ago, though.

But it reads as if the subject of each chapter was determined by casting the I-Ching.

There is at least one Dick novel that is supposed to have been created just that way. I am no longer sure if it was this one or not.

I wrote a post on the subject of different kinds of misdirection, actually:

https://mishaburnett.wordpress.com/2013/06/22/when-what-you-know-aint-so-part-ii-with-spoilers/