As discussed in some of my previous Elements of Wargaming installments here on the blog, Wargames are designed to be faithful enough to war and real-world experience to be useful in a real-world scenario. I recently was directed to a further proof of this, in an article discussing the resurgence of Wargaming in the US military’s mind. The experience of forming a plan and encountering a live opponent at the helm of the other side’s forces, being opposed by an intelligent, unpredictable force is considered vital in an age where a single missile might destroy a naval vessel, a single aircraft costs a hundred million dollars, and training a soldier takes longer in part to familiarize them with the use and counter-operations for a host of modern equipment that surpasses our senses. Mistakes are more costly than ever. In this vein of thought, there are a host of different complexities and nuances that a good Wargame—especially a modern or futuristic Wargame with tanks, airplanes, radios, and the vagaries high technology brings.

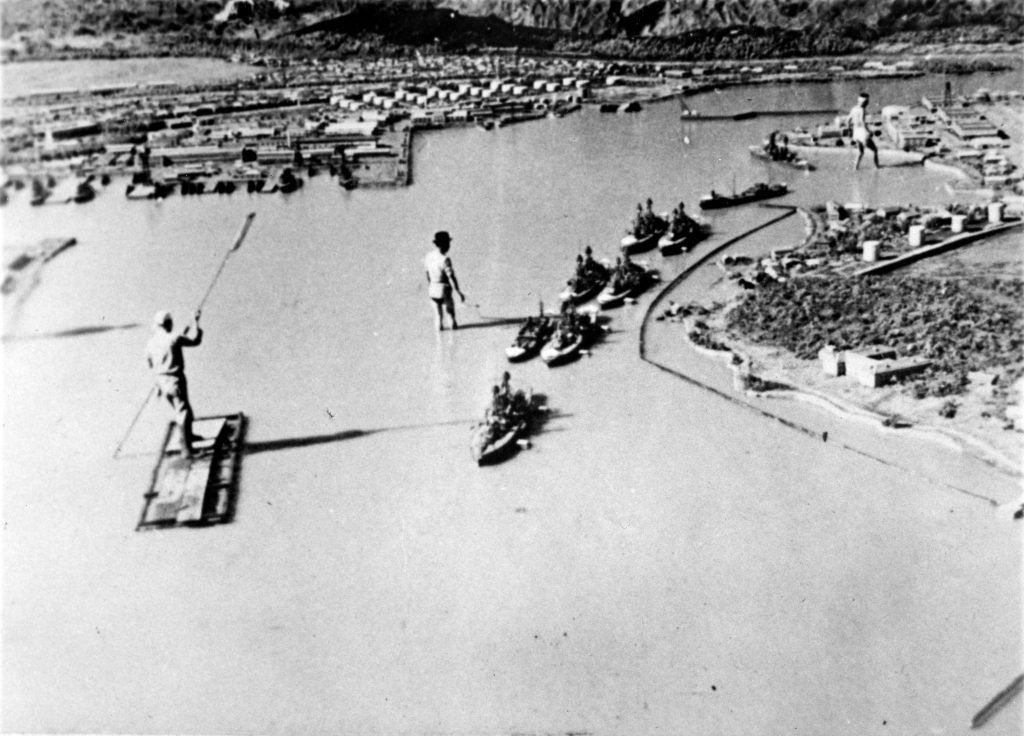

Japanese model of Pearl Harbor, showing ships located as they were during the 7 December 1941 attack. This model was constructed after the attack for use in making a motion picture. The original photograph was brought back to the U.S. from Japan at the end of World War II by Rear Admiral John Shafroth, USN. Collection of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

From the design side, Wargames are an intimidating and uphill challenge: Including too many of these nuances or accounting for every detail can make the game bloated, clunky, arcane—essentially unusable. Add to the huge amount of detail in general, you have organizational issues for different forces and representing all or at least the majority of important groups accurately. Even further, you have to balance the game so that it does not favor one side versus another, which is the heart of the fun of the game: You have a chance for victory, you must merely snatch it from fate and your opponent. The need to produce a system which unifies all the disparate elements in a fashion which is clean enough to utilize in a time-efficient manner but also maintains the balance of play where the challenge can be dialed appropriately and usability remains high is a staggering call.

For those of us who are not military professionals seeking to make such a game for the future of a nation, prevent waste and the cataclysm of an unprepared or ignorant commander of an armed forces body, we can relax a little bit. Most Wargames you’ll see played carry the principles well but are willing to nip and tuck to ease the load this puts on designer, rulebook, player, and cost-of-play. Just as you are not risking real troops, you are probably not playing a game so polished and comprehensive. This is the horseshoes and hand grenades principle which drives good design. Below are a few examples:

- Tanks typically have armor that is stronger on their front and significantly weaker on the sides, but being at a slight angle presents an even stronger, angled face. The best way I have seen this modeled is that instead of using a ninety-degree facing for front, sides, and rear, the game models the flat face of the tank’s front armor as a linear plane, with everything on the opposite side of the line being considered ‘in front’ for firing at the tank. This is clean, simple, and a reasonable accommodation to the reality

- Morale tests or checks being a single die roll, getting a bonus for their commander if he is nearby but taking penalties from things like severe casualties, being outnumbered heavily, or being under an artillery or magical bombardment or airstrike

- Aircraft pilot stress after complex or difficult maneuvers, eliminating their ability to continue performing more until they have de-stressed with easy maneuvers; this reflects the effect of serious G-forces on the body (blood flow in particular)

- Including drift and slight inaccuracies for long-range artillery bombardments, a feature visible even in futuristic and modern games in order to balance the area-of-effect damage against individually-modeled forces, such as groups of infantry.

There are many more, of course. Every good Wargame would have a dozen examples or more of good streamlining as it reflects reality, even if that ‘reality’ has splashes of fantasy like dragons or space aliens.

So how does this benefit us? The visualization of the Wargame can certainly benefit the explanation and learning of a Wargame by a new player, and the best kind of approximation can help you understand something in a new way. A rule giving a good chance for infantry to survive a massed artillery barrage by going to ground, limiting their offense and mobility in order to survive, can reveal a new understanding for commanders and those who have not experienced war. Additionally, simplifying the calculations to clean charts, or using one die roll with a list of modifiers instead of three or four different rolls saves a lot of time; computers can do these calculations quickly, but if you prefer tabletop games with your friends this is a key consideration. This empathy and the ease of education and the time saved are a few of the many benefits.

What are some of your favorite approximative rules in your favorite Wargames?

-Zac

For miniature wargames: terrain.

Most wargames have an explicit ratio of figures:men. One figure may represent 10 historical men. Easy enough. Though it doesn’t always have the same explicitness as for figure, the same is true of terrain features.

The tabletop may look like a bowling green with a mesa and a small copse of trees. In actuality the smooth level ground consists of rolling ground, odd random trees rocks and gullies. That liver shaped piece of cloth doesn’t directly show a diving line between ‘trees be here’ and ‘trees be not here’, but instead demarcate an area in which certain game effects apply. Inside the line there are enough trees to make shooting and movement difficult. That one building probably represents a small farm with house, barn, and outbuildings. Those four buildings represent a small village of two dozen houses.