One of the hardest and most worthwhile elements of Wargaming, indeed the part that never stops, is developing a mastery of the intricacies. Learning a new Wargame might be done in a few days, but getting to the point where you can manipulate the forces under your control, develop them, and predict their interaction with your oppenents’ schemes to begin having games that are not just fun but also beautiful… That is the goal. Each system is a little different, and while the similarities make transitioning easier, you can anticipate a learning curve when you pick a new one up. Myself, I love Wargames for this mastery and nuance almost entirely; more satisfying than winning is playing well and I am not alone in the community for this peculiar love. I keep learning new games in order to widen my ability to play and learn from more people, to see more styles and to learn how designers represented different elements of combat: This one has static armament for these units, while this one allows you to change their loadouts; This one is scaled out and has ammunition carriers, while this other is more squad-oriented, fast-paced enough that resupply does not factor in. This love is tied closely with my teaching at a Liberal Arts academy, where I get to practice the same learning method I teach my students to use: Grammar, Logic, and Rhetoric.

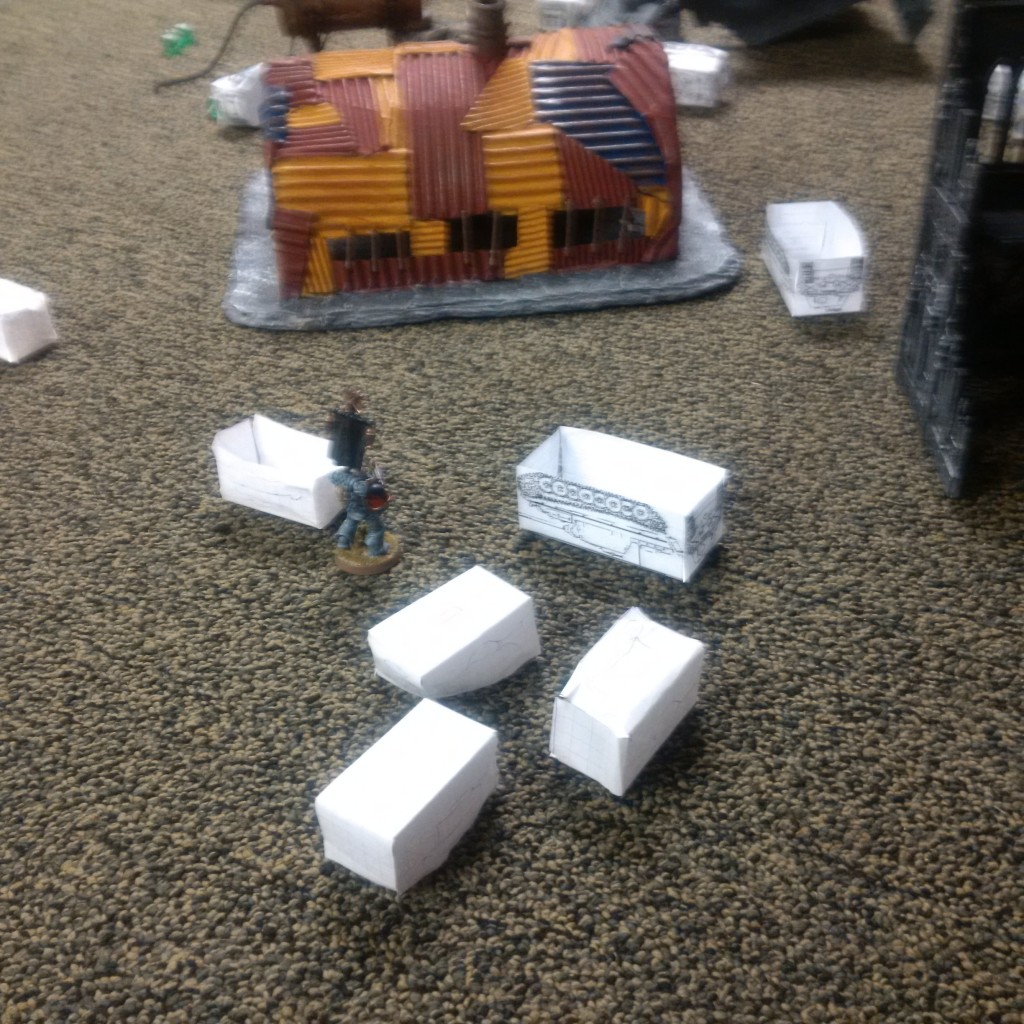

Grammar can be summarized in asking, “What are the rules?” and usually there is a book for that. A longtime friend and Wargaming associate of mine introduced me to Flames of War, a World War II micro-level combat simulation. I illustrate my first battle after skimming the rulebook— I’m playing Germans against Americans, and we’re keeping things nice and simple. No AA guns, no airstikes, no artillery strikes, no infantry; just tank squads.  We’re learning the game together, so we decided on a sparse terrain environment: Several low hills, a couple buildings, and a river running slantways across the table. However, unfortunately for my opponent, the river we put down actually prevented his tanks from traversing the river, combined with a defensible spot within capture distance for my squad.

We’re learning the game together, so we decided on a sparse terrain environment: Several low hills, a couple buildings, and a river running slantways across the table. However, unfortunately for my opponent, the river we put down actually prevented his tanks from traversing the river, combined with a defensible spot within capture distance for my squad.  We both learned several things about the game here, looking at the rules: Flames of War is designed for gritty battlefields with a lot of terrain and also that the rule-set differentiates terrain types quite intimately: Hedgerows are different than fences, ploughed fields are different than open fields, and so on. This is but one possible example of how rules change from system to system, and how even a read-through of the rules won’t get your mind to grasp the system as a whole— Experience with a great many situations is needed before you understand the nuances.

We both learned several things about the game here, looking at the rules: Flames of War is designed for gritty battlefields with a lot of terrain and also that the rule-set differentiates terrain types quite intimately: Hedgerows are different than fences, ploughed fields are different than open fields, and so on. This is but one possible example of how rules change from system to system, and how even a read-through of the rules won’t get your mind to grasp the system as a whole— Experience with a great many situations is needed before you understand the nuances.

Logic is the phase where you begin combining and asking questions of the pieces which you assembled in the Grammar phase. Is it better to get the extra shot from remaining still, or close in to get the extra bonus for short range? Is it better to advance and set up in the hedgerow overlooking the objective, or should I stay in the building back here where it’s safer? Is this a system where I can opt for this cheaper unit because a few points of armor doesn’t matter so much, or is this a quality squeeze for that role in my force? Here is where the real experience begins, and the intellectual chops start getting a workout.  In this subsequent battle, I defended against his onslaught with half my force using an ambush special rule. He crept up as close as he could manage and then rushed the bulk of his troops around the north side, just as I anticipated and I sprang my trap, with a squad of tanks ‘appearing’ from ambush on his flank and tearing his main force to shreds.

In this subsequent battle, I defended against his onslaught with half my force using an ambush special rule. He crept up as close as he could manage and then rushed the bulk of his troops around the north side, just as I anticipated and I sprang my trap, with a squad of tanks ‘appearing’ from ambush on his flank and tearing his main force to shreds.  Unfortunately, he rolled well and my two tanks guarding the point failed to hold out against his squad of light tanks on the other side.

Unfortunately, he rolled well and my two tanks guarding the point failed to hold out against his squad of light tanks on the other side.  He answered the question, “How much should I respect the ambush?” wrong, but I answered my own question incorrectly: “Can my command team hold off his squad of light tanks?” Mine proved the more grievous mistake, as he took the victory home in his bag, having captured my objective.

He answered the question, “How much should I respect the ambush?” wrong, but I answered my own question incorrectly: “Can my command team hold off his squad of light tanks?” Mine proved the more grievous mistake, as he took the victory home in his bag, having captured my objective.

Rhetoric is the final part of learning, and it means persuading others to your viewpoint or contributing to the community, such as writing a thesis paper in grad school.  In this next battle we did the same scenario, except we swap armies. He elects to put both his squads in ambush, which means I had the run of the field until he struck. Employing what I had learned from trying to set up my own ambushes. I blitzed forward to prevent him from springing his trap- I had run into the problem of their limitations in the previous match.

In this next battle we did the same scenario, except we swap armies. He elects to put both his squads in ambush, which means I had the run of the field until he struck. Employing what I had learned from trying to set up my own ambushes. I blitzed forward to prevent him from springing his trap- I had run into the problem of their limitations in the previous match.

Because of line-of-sight and other restrictions, I was able to force him into an awkward deployment away from the objective, and his long-range shots were not able to drive me away.

Because of line-of-sight and other restrictions, I was able to force him into an awkward deployment away from the objective, and his long-range shots were not able to drive me away.  There was a good general exchange after these matches, and we drew a few conclusions will continue learning as we keep playing.

There was a good general exchange after these matches, and we drew a few conclusions will continue learning as we keep playing.

In Wargaming, as in life, defeat and victory can often hinge on a single overlooked detail, failure of a single step in a complex plan, a gamble that soured, or a fluke of fortune but more often it is firmly ensconced in experience and execution of tested plans. When introducing new players, I have found it helpful to get two new players to compete rather than myself for the first game so that nobody feels outclassed in experience and familiarity with the rules and the already-developed grasp of the arithmetic of the game; Wargaming can feel very personal and it helps to remove these distractions at the beginning rather than later. It’s the little things that matter large. An eternal student, I have found tremendous enjoyment in Wargaming for its development of mastery. What are your favorite elements of Wargaming?

– Zac

>In Wargaming, as in life, defeat and victory can often hinge on a single overlooked detail, failure of a single step in a complex plan, a gamble that soured, or a fluke of fortune but more often it is firmly ensconced in experience and execution of tested plans.

Truth.