Future Skirmish, Part 1: The Closing of the American Frontier

Friday , 21, August 2015 Uncategorized 2 Comments

The Closing of the American West marked the beginning of a new kind of skirmish.

It is an important idea, as the U.S. Frontier is almost entirely responsible for the idea of the country’s identity as a moving, progressing nation, unlike its European originators, with their rigid, nationalistic, non-expansive societies. It is also the source of the theory that America was due for a major identity crisis the moment it could no longer expand.

The “Closing” was supposed to mark this crisis, but of course, just as Hari Seldon couldn’t possibly predict the individuality of the Mule disrupting the carefully measured probabilities for the future, it is abundantly clear in retrospect that the historians have simply missed the timing. The West didn’t close at the turn of the 19th Century.

Not that it stopped historians and artists from drawing inspiration from that marker. In movies such as the Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, to books like Blood Meridian, Louis L’Amor’s perpetual West, or even The King in Yellow, and countless modern histories, the “Closing” is viewed as an important – if tragic – end to the American Dream of vast, endless adventure and diversity.

20th Century American Westward Expansion

However, not only did Westward migration occur in large numbers during and after the Great Depression, but the World Wars (esp. II) provided a new – if artificial and temporary – national frontier by way of the Marshall Plan. More importantly, Alaska and to a much lesser degree Hawaii provided a fertile frontier to America for the first 50 years of the 20th century.

Even their official statehood at the end of the 1950s did not close the West, because we were already looking to the Galaxis Americana.

No. The American West didn’t officially close in North America. It didn’t close on the Western Hemisphere. It didn’t even close on this planet.

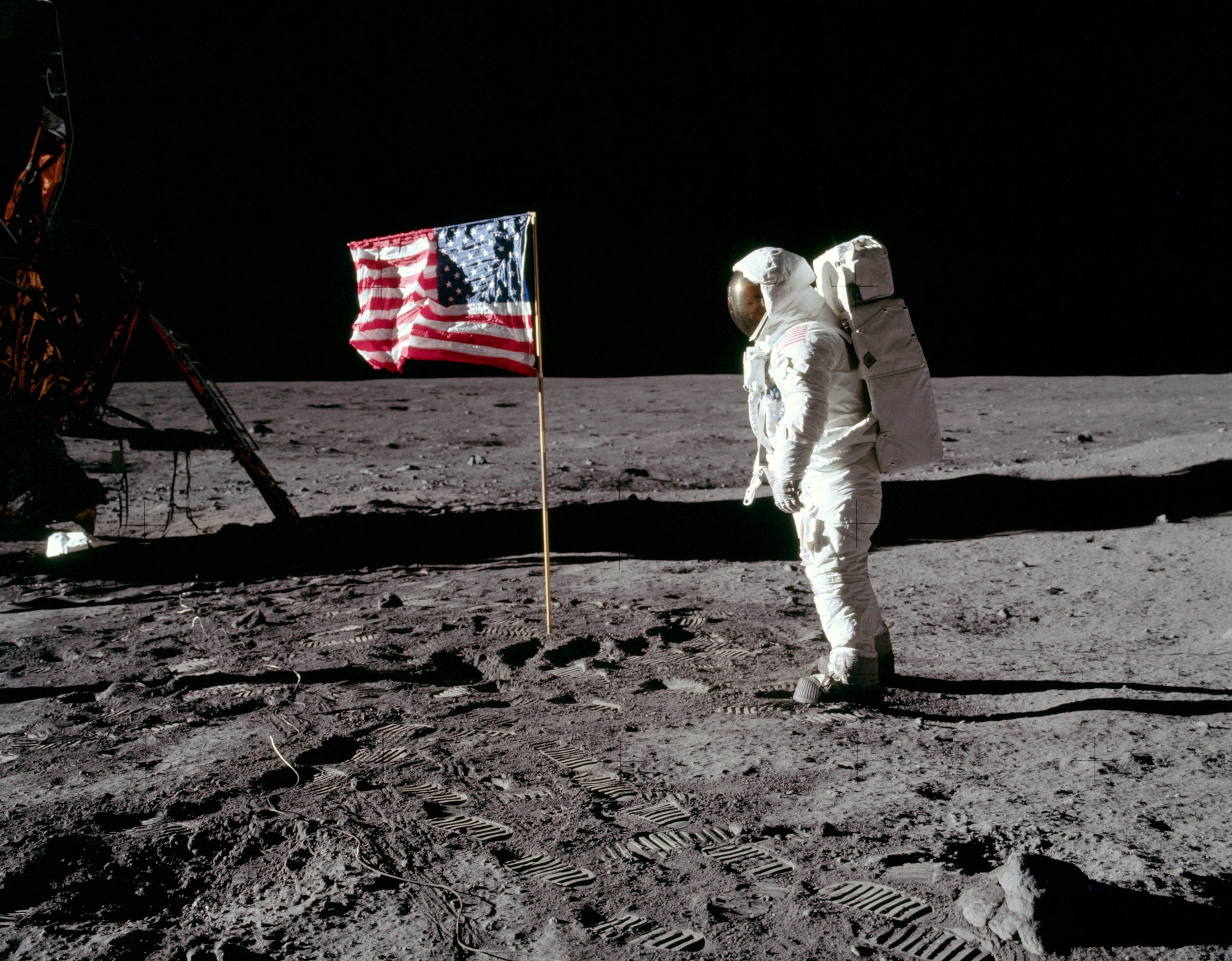

It closed on the Moon.

On July 20, 1969, it was far from clear that U.S. explorers had taken their final steps into new territory. In fact, most people and popular narratives at the time simply assumed that a lunar gold rush, or perhaps Martian claimstaking was just around the corner. Jeff Sutton in Apollo at Go! First to the Moon, and of course Beyond Apollo had been writing about such adventure for more than a decade.

But after a handful of more trips to the moon and fewer then twenty Western exploring astronauts setting foot on the surface, it was over. More importantly, the U.S. economy and standard of living, after decades of vaulting the previous generations, showed its first significant signs of faltering, which lead to increasingly hysterical prop-ups. America had begun its Byzantine era.

While grand strategy and large-scale war and politics are more sweeping (perhaps even more accurate or measurable) topics when considering the future, a lot can be learned from the skirmishes of the day.

Many contemporary skirmishes since 1969 involving at least one organized group have been classified in the popular imagination as something else: incidents, murders, sieges or police raids. However, I think it is useful to examine the modern skirmish from a political and military perspective in order to best project possible future innovations.

So, over the next few weeks, I’ll be taking a look at recent skirmishes in the U.S. since the Moon Landing/Closing of the American Frontier, and speculating about the potential ramifications for future conflicts.

The Pine Ridge Shootout

Since we’re talking frontier, let’s go back to cowboys and Indians, with the Pine Ridge Shootout of 1975.

The Setting: Two years after the siege at Wounded Knee (involving competing Indian factions at the U.S. Government, a skirmish that I’ll address in a later post.), tension between Ogalala Sioux tribal chairman Dick Wilson and his GOON (Guardians Of Ogalala Nation) militia against the American Indian Movement who suspected the GOONs of having murdered as many as 60 AIM-member Indians had not subsided.

The FBI sent two agents into the Jumping Bull Compound to serve an arrest warrant, apparently only armed with service revolvers and one shotgun, with heavier guns in the trunks. Each agent was driving his own car, and, within minutes of arriving to the Compound, identified a person of interest and pulled him over.

Ramifications

The Skirmish:

Agent Ronald Williams radioed immediately that the occupants of that car had dismounted and were armed. A third agent, about 12 miles (or 15 minutes or so) away, heard the radio, including shots fired, unlocked his high-powered rifle, and took off for the compound.

One of the agent’s cars after the one-sided shootout. The trunks were open on both cars, an apparent unsuccessful attempt for the officers to fight their way to better guns.

At least seven gunmen fired on the agents, either from the pulled-ver car or nearby tents and homes. Although the two initial agents were incapacitated early, firing no more than a dozen return shots (if that) before succumbing to their wounds (after which both were ultimately killed at point blank range with shots to the head), the third agent and a contingent of BIA officers were able to even the odds in manpower.

Who Won Tactically?

The Indians of AIM. Not only did they accomplish an ambush and defense, they didn’t lose a soldier. Casualties matter much more in skirmishes rather than in larger battles (where the winning side can afford to suffer greater losses than than the loser), and in this skirmish in particular, aside from an AIM member who died during the pursuit, only one of the attackers was ever caught and successfully prosecuted.

As skirmishes go, the side that started it couldn’t have hoped for a much better outcome.

The Main Advantage:

Superior firepower. While the first two agents fell due to a combination of ambush and more guns, the full contingent of police can’t make the same claim: they knew what they were getting into and had equal or greater numbers. They were held off from their objectives for five hours, which provided ample time for the ambushers to prep, escape and cover their participation.

Thus, better guns – high powered rifles, combined with an attack that was able to easily and effectively switch to the defensive, may have made the difference in this engagement.

The Future:

This skirmish took advantage of one the easiest things to project into the future: tactical technology advantage. Martin Van Creveld and many others can tell you that technology is – if you’ll excuse my pun – a double-edged sword for many reasons, but all other things being equal (including the will to fight), a tech advantage is still a tech advantage.

The Indians at Jumping Bull Compound had the advantage of scoped, high-power rifles, and put more than 125 bullets into the first two agents’ cars and bodies before the pair got off five shots between them. Even when reinforcements arrived against the ambushers, the return fire from now reinforced defensive positions was too accurate to allow for a timely rescue.

So, knowing that technology will change (and possibly improve) in the future is the easy part. What is hard to gauge is the political minefields (as demonstrated with the the DARPA XM3) and adoption rates a new technology might face. What is clear is that the FBI along with a variety of other federal agencies, including the Department of Education, are now quite a bit more militarily armed than they were in 1975.

So, for the Future Skirmish – Technology Advantage category, I predict:

The winning side will have a railgun, because a) the technology is in development now and b) because – like the Gatling gun a century or more before it, and as evidenced at the Pine Ridge Shootout – the ability to throw an insanely high amount of projectiles at your enemies with a mobile one-or-two man crew is a fundamental advantage at the skirmish level.

The even flashier, but much less realistic DREAD silent weapon system, which boasts an ability to fire 120,000 rounds per minute, seems (if it were ever to be developed) to be far too impractical and expensive for use in a skirmish, ever. Not to mention it would be a certain way to win a small battle while ensuring defeat in the war. It would be like taking a nuke to carve the Crazy Horse Memorial.

In later posts, I’ll take a look at a number of other American skirmishes of the post-moon era, and see what clues we can gather from them to look into the future of skirmish.

Including:

- The assault on the Branch Davidian Compound, Waco (Communications)

- The armed occupation of Wounded Knee village, South Dakota (Will)

- The Manson Murders (Ideology)

- The 1992 Los Angeles Riots (Identity)

- The Culwell Center Attack (Defensive Tactics)

- And others.

Nice. Good insights on both the Moon and the railgun. You’re asking good questions.

It really seems like there should be more comments for these excellent posts, but I’m not sure there’s much to add beyond “I’m looking forward to the next installment.”