I recently received this comment on my Appendix N series recently from a student of classic science fiction and fantasy calling himself Atlemar:

You make the observation here that “It used to be normal for science fiction and fantasy fans to read books that were published between 1910 and 1977. There was a sense of canon in the seventies that has since been obliterated.” I’ve looked at your other entries, and unless I’m missing something, this isn’t a well-supported point. Gygax read these, and it could be his personal canon, and St. Andre read these, but the rest of fandom? I’m not saying you’re wrong, only that I don’t think you present enough evidence that these books mattered to the rest of geek society as they did to Gygax.

You know, I think this is a pretty fair question. It’s one I’ve written extensively on, but it’s one I enjoy addressing. You can, for instance, take a look at what books were translated when fantasy first took off in the Italian market. There is also a coloring book published in 1975 that sums up what the default view fantasy was at the time. The overlap here between these things and Gygax and St. Andre shows that these pioneers of role-playing were well within the bounds of what passed for normal in the fantasy fandom of their day.

You know, I think this is a pretty fair question. It’s one I’ve written extensively on, but it’s one I enjoy addressing. You can, for instance, take a look at what books were translated when fantasy first took off in the Italian market. There is also a coloring book published in 1975 that sums up what the default view fantasy was at the time. The overlap here between these things and Gygax and St. Andre shows that these pioneers of role-playing were well within the bounds of what passed for normal in the fantasy fandom of their day.

Of course, the supply of great fantasy and science fiction was so small in the days before Sword of Shanarra and Star Wars that publishers had no other choice but to reach several decades back just to have something to sell. Classic stories of the twenties were reprinted in the forties, often picking up Virgil Finlay illustrations in the process. Morgon has documented here at Castalia House the extent to which classic stories from Weird Tales were anthologized during the sixties in his posts on building a Weird Tales library. Meanwhile, take a look at how authors like A. Merritt that are all but forgotten today remained in print all the way through the seventies where they would have been side by side superstars like Roger Zelazny.

It is the relatively small amount of available fantasy combined with the relatively ease of obtaining the old stuff which allowed a canon to even exist at the time. Or rather, as Ken St. Andre pointed out, it is the deluge of fantasy and science fiction stories of the eighties that caused that canon to be wiped away from the collective consciousness of fandom during the eighties.

Nowhere is the culture shift more evident than in the elevation of Tolkien as the go-to model for how fantasy is done. Before about 1977 or so, he was still popular, of course. He nevertheless represented merely one approach among many. And his influence was easily eclipsed by Edgar Rice Burroughs in those days. For anyone that defines fantasy in terms of Tolkien and his imitators, that is almost unimaginable. But I think anyone that begins to read works from the time period will have to agree that that’s the case.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. Burroughs is the first fantasy author mentioned by Gary Gygax in the Forward [sic] of Original Dungeons & Dragons. Elements of the Barsoom stories show up on the encounter charts. Thanks to the Burroughs Estate, the rarest and most expensive TSR product today is Warriors of Mars. Ken St. Andre was far from being the only person in fandom that was a member of Burroughs Bibliophiles. (He told me himself that you can’t overestimate the influence of Edgar Rice Burroughs on his work.) But take a look at the other “second” role-playing game that was created and you’ll see mangani from Burrough’s Tarzan series there as if they were a natural part of any fantasy bestiary. Finally, J. Eric Holmes, the editor of the first “Basic Set” rules for D&D even wrote a trilogy of novels based on Burroughs’s Pelucidar series.

Now… either it’s a total coincidence that just about everyone involved in the earliest phases of the role-playing hobby was really into the work of Edgar Rice Burroughs… or else maybe… just maybe… Edgar Rice Burroughs was phenomenally popular well into the seventies. Given that people dressed up like Dejah Thoris at conventions and Rocky Balboa learned to read from a Burroughs novel in Rocky II, I’m going to go with the latter.

The other fantasy giant on the Appendix N list? Without a doubt it’s Lord Dunsany. Consider this passage by Lin Carter from the introduction to At the Edge of the World:

The stories in this book excited the enthusiasm and molded the writing styles and themes of virtually every important fantasy writer in the first half of the twentieth century. H. P. Lovecraft adored Dunsany and emulated him in such fantasies as The Dream-Quest of the Unknown Kadath. James Branch Cabell enjoyed Dunsany and made frequent references to him in his letters, essays and autobiographical ventures. Both Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp were influenced by Dunsany. So was Clark Ashton Smith, in his Zothique; and I see traces of Dunsanian influence in the writings of Jack Vance and Fritz Leiber, and perhaps Robert E. Howard as well.

Notice that to convey the scope of Dunsany’s influence, he cites six of the most significant and influential authors from Gygax’s Appendix N list. Note also that those same authors are cited by Gygax as being “the most immediate influences” on AD&D in the 1979 Dungeon Masters Guide. Look on the back of the Lord Dunsany volumes from the Ballantine Adult Fantasy line and you’ll see Lovecraft and de Camp quoted there. You’ll see some of those names repeated in Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 essay “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” as well, just like you’ll see Appendix N authors in everything from this year’s Retro Hugos to endorsements on the back of old paperbacks.

Yes, the authors on the Appendix N list are largely obscure today. But in the seventies, they were virtually synonymous with fantasy even outside of the nascent tabletop role-playing scene. No, Appendix N was not the canon. But it was close enough to it that few fantasy fans can look at it without insisting that the people that they think are the best in the field be incorporated in it. You really can’t blame them for it, either, because it really is a great list. If you survey every author on it, you’ll not only find out not just where entire swaths of the early role-playing games came from. You’ll get a crash course on the history of science fiction and fantasy genres as well. It’s that comprehensive.

And then guys like me, who were teenagers in the mid to late 80s, could still tread both fields, so to speak. I remember clearly the rise of Tolkien-inspired fiction into best-seller status, and I liked a fair bit of it at the time (although mostly because it was derivative to Tolkien—I’ve since decided that hewing too closely to Tolkien only invites rather unfavorable comparisons on your work.) But I also clearly remember whole shelves at the bookstores and libraries of Burroughs. For the better part of thirty years, I’ve held out both Tolkien and Burroughs as my absolute favorite authors.

I think the secret to successfully imitating either of them, to some degree, is to do it more subtly, however. Both the 60s rehash of overtly Burroughsian pastiche and the 80s and 90s overtly Tolkienian pastiche were faddish precisely because they didn’t do anything NEW with the ideas, they simply spit them out.

-

I would like to provide a data point in reply to Atlemar’s comment elsewhere:

Age: 60

Neither parent worked as a librarian or in a bookstore, and while I have worked in retail books, that was not until 1990.By the time I was 25 (1981), I had read one or more books by each of the authors on Gygax’s Appendix N list with the exceptions of John Bellairs and Manley Wade Wellman.

From my point of view, the Obliteration of Canon and the resulting generation gap is quite real. I can only second your comments on the contributions of ERB and Lord Dunsany: their influence was profound.

-

Thirded.

Going to conventions and meeting people well outside my peer group, we all had one thing in commong – having read most of these authors.

-

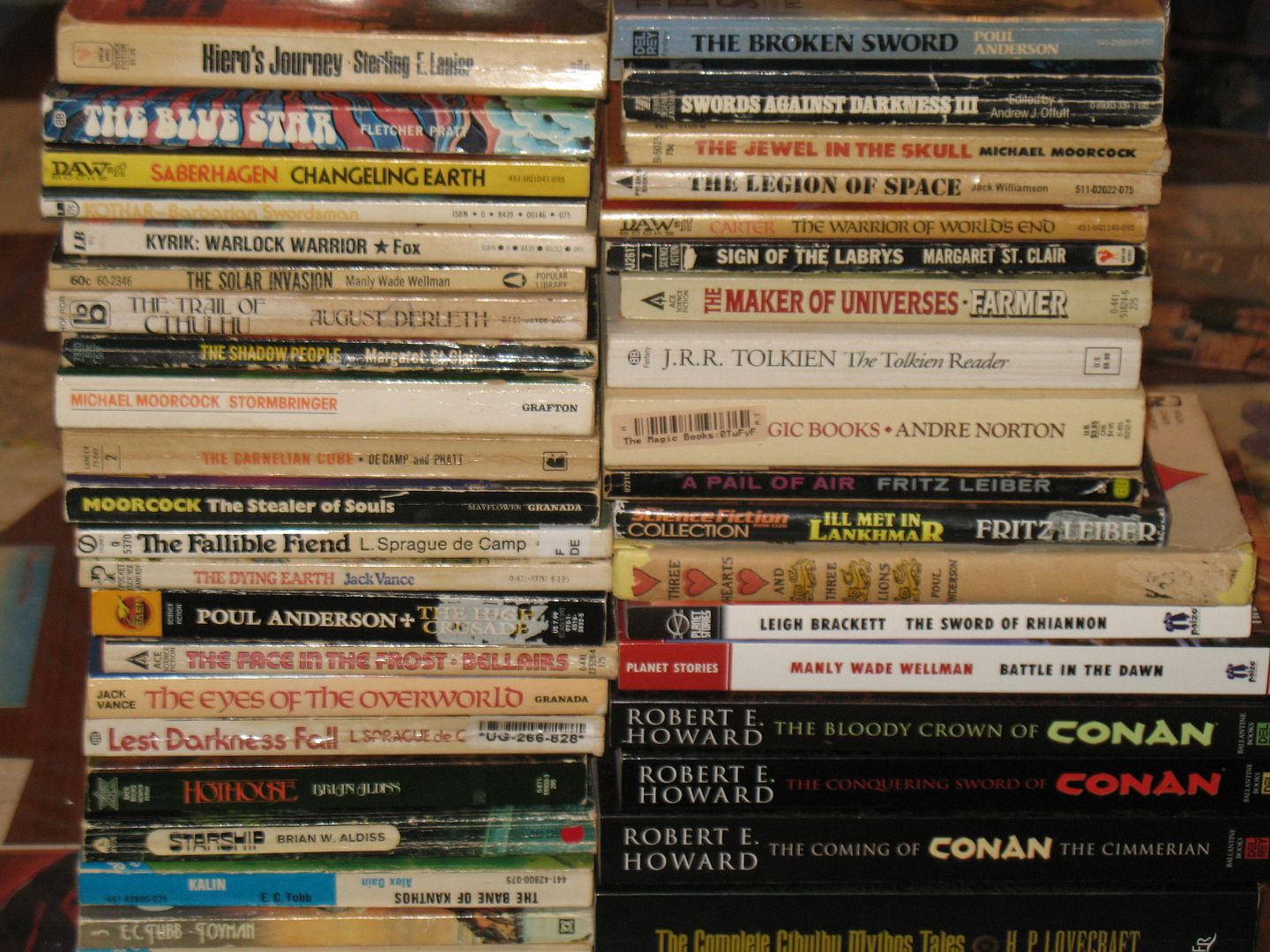

I still have some of my older books. Whenever I find a copy I used to buy them even if I had a few already.

Now I cannot read except larger print so I’m not sure if I should continue collecting paperbacks.

You cannot over estimate Burroughs, read his books and they lay out the adventure style perfectly. RE Howard doesn’t receive the credit he deserves.

With respect to Dunsay, in her book of fantasy and science fiction literary criticism, The Language of the Night, Ursula LeGuin discusses how every fantasy writer has an early period of writing bad Dunsany pastiche.

If a multiple Hugo and Nebula winning author of the period says imitating Dunsany is part of the natural writing path of a fantasy author I think it is safe to say Dunsany loomed large well into the 70s.

“in the days before Sword of Shanarra and Star Wars”

The choice of making Princess Leia a Princess always seemed odd to me, especially considering how the later films treated her, and her mothers, royalty. In the First prequel we discover she is elected Princess I guess. Almost as if Lucas had second thoughts after the fact.

But after reading this article and looking up Burroughs and finding the novel “Princess of Mars” I am wondering if the science fantasy of Star Wars was not heavily influenced by Burroughs.

Also the innumerable different aliens in Star Wars seems to have parallels with the many different species found in Burroughs works.

Evidence of Burroughs influence on Star Wars would support at least his pre-1978 canon status.

Disclaimer: I have not read any Burroughs. These are just observations I have made when looking up what he wrote.

-

Get thee to a ‘Princess of Mars’ and read it. You won’t regret it.

-

Oh, and Andre Norton. Just about everyone had read Norton.

The advantage of Norton (and Heinlein, and to some extent ERB and Lovecraft) was that had been published in hardback editions with wide library distribution in the 50s and 60s, and the Public Library stocked them. (They also had John Bellairs). You couldn’t dig up a hardback copy of Leigh Bracket or RE Howard or Zelazny or Anderson but you could always fine handsome editions of Norton or Heinlein juvies or Clarke in the children’s or adult SF?F section. Gateway drug.

You couldn’t

Lovecraft, Howard, Burroughs, Poe, Stoker, Jackson, Heinlein, Dick, Wells, Bradbury, Card, King.

And a jillion others. That was 1985.

I believe the generational disconnect began in 1990, where we have previously traced the public admission by publishers of the distinct “need” to “broaden” the genre: ie make them all “accessible” romantic fantasies for mass consumption.

Another bit on the Burroughs popularity:

In the late 70s Heritage miniatures released an entire line of Burroughs 25mm lead Mars figures.

They were widely distributed enough that even my small town hobby shop (not a game store!) stocked them circa 1978. I bought a bunch for D&D.

My impression was that the supported availability of coherent game worlds, often with their own fiction lines, killed the canon. This was not really the intent of Gygax et al originally – worlds like Greyhawk or Blackmoor, or GDW’s Imperium or even Glorantha, were mostly very lightly sketched out.

But pressure from fans to learn more about these worlds, from companies to publish content, and from game designers to find work led to huge explosions in the detail available for “in house” settings. The same thing happened to Star Trek and Star Wars, of course.

So in the 1970s and 80s to “get” RPGs you really needed to read a decent chunk of the canon. Gamers stole ideas mainly from popular SF and fantasy.

By the 80s and 90s in the Dragonlance, Forgotten realms, Battletech, Warhammer, etc. era, there is so much content available for the licensed in-house universes that it was quite possible and indeed necessary for fans of their universes – like the Star Wars and Star Trek fans before them were driven, almost by necessity, to focus only on the new game-specific content. With scores of forgotten realms novels and supplements around to master, who had time or energy to read Burroughs or Vance or Conan?

(wandering back, two weeks later…)

Thanks for following up! This answers my question and supports your point sufficiently. (I’ve been writing audit reports all week, that’s why I’m talking like this…)