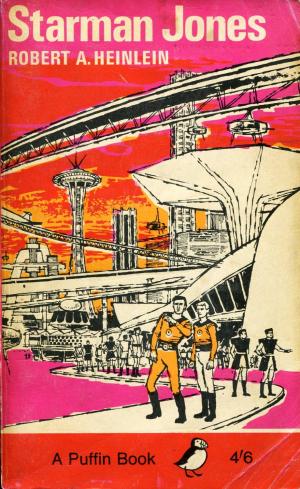

I just finished listening to Robert Heinlein’s Starman Jones, published in 1951. It’s a fun little novel and the narration by Paul Michael Garcia is good, he does a variety of voices well.

I just finished listening to Robert Heinlein’s Starman Jones, published in 1951. It’s a fun little novel and the narration by Paul Michael Garcia is good, he does a variety of voices well.

I remember the title from my high school days when I read absolutely everything I could get my hands on by Heinlein, but it wasn’t a book that made a huge impression on me. It has probably been close to forty years since I read it last—to be honest, I only picked it up because it happened to be one of Audible’s Daily Deals and I was able to snag it for three bucks. (If you’re not an audio-book listener, trust me, that’s a steal.)

Hearing it now I was struck by two things. First, it’s a very political book, although I didn’t understand that as a teenager. The main character, Max Jones, lives in a society where all professions are controlled by guilds, and you can’t work in a trade unless you are either born into it or pay a fee for membership that is well out of the price range of an unskilled laborer.

The polemic isn’t heavy-handed, but it’s clear. Max is a poor farm boy who wants to go into space, but despite being a genius with an eidetic memory, he has neither the connections nor the cash to get into a spacefairing guild legally.

The other thing I noticed is that the science is stupid.

Okay, maybe that’s a bit harsh. But here we are, several hundred years into the future (the Jones farm is said to have been in the family for four hundred years) and have starships with artificial gravity that can accelerate at dozens of Gs, and have plotted points in space that allow for instantaneous travel over light-years, and how are these paragons of technology navigated?

By making calculations on paper, looking up the conversion from decimal to binary in a hardbound book, and punching the binary sequence into the computer. (The computer. There is one on the ship, and it’s used exclusively for piloting.)

In fact, the big climactic scene in the book is when they have lost the only copy of the conversion books that the ship carried and Max has to do the conversions in his head, because if the previously mentioned eidetic memory.

Now, wait just a minute here, I can hear you saying, you’ve got to cut Heinlein some slack—he was writing in 1951 and that was how computers operated in those days. But that is exactly my point.

Hard SF ages like unpasteurized milk left on the counter overnight.

It was particularly noticeable because the rest of the novel—the non-sciency bits—aged very well. Max’s frustration at not being allowed to do the job that he has the talent and desire to do is very real and very relevant to today. The interpersonal relationships are believable, given the drastically striated society. The tension is well handled and the dialogue snappy. It’s solid pre-New Wave Heinlein with all of the usual suspects—the naive kid, the scoundrel with a heart of gold who takes the kid under his wing, the benevolent and unflappable mentor, the unscrupulous rival who resents the kid’s talent, the cute girl who is smarter than she lets on. Not a grand slam like The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress or Starship Troopers, but a good solid double.

The parts that are purely fantastic—artificial gravity, alien planets with breathable atmosphere, the FTL translation itself, the supersonic train that runs past the main character’s farm—I had no trouble buying within the context of the story. It was the bit that was most “realistic” when it was written that caused me to stumble, the in-depth description of making calculations and programming the binary computer. (I was actually wondering what the computer was for, since all the math was being done by humans.)

Good stories can and do outlive the science that they are based on. As I’ve mentioned before, A Princess Of Mars was Hard SF when it was written. The concept of Mars as a world that was once like Earth before the oceans dried up—and the corollary that Earth would suffer the same fate in time—was considered a reasonable scientific hypothesis at the time that E R Burroughs was writing. Science has moved on considerable since then, but modern readers are able to accept Barsoom even though we know it’s nothing like the real Mars because the story of John Carter, Dejah Thoris, and Tars Tarkas is timeless and could be set anywhere. It’s a story about people.

Stories that are about science don’t fare so well. The ecological scare SF of the 1960s and 1970s—John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up and Stand On Zanzibar for example—don’t hold up today.

What is plausible and reasonable today is absurd tomorrow. But the fantastic is eternal.

You might be interested in reading the intro to the Baen edition, by RAH’s biographer William H. Patterson, Jr.

http://www.baen.com/Chapters/9781451637496/9781451637496.htm

And I’ve always loved how Heinlein transitioned from the penultimate chapter to the last chapter, “The Tomahawk”. Which also happens to be the title of the first chapter.

Excellent post.

Like Misha, I remember reading and enjoying STARMAN JONES, but it didn’t blow me away. Also like Misha, I’ve said for decades that “Hard” SF tends to date badly. Obsolescence is practically baked into the cake of the entire “game.” Oh, and it IS a game:

Thus, like other games and sports, each individual contest/story is more-or-less casually forgotten except by the most fanatical adherents of that team/author. The main intrinsic value is the “victory” at that point in time. Even gold medal winners can later be cast down when found wanting in some technical category.

Such a viewpoint is almost diametrically opposite to the aspirations of storytellers of old who strove to entertain their audience through wordcraft and stirring plots…and perhaps gain literary immortality if their tales fulfilled that task well enough. The Club for Buds of Hard SF is not one for old men or old stories.

Whereas I still thoroughly enjoy STARMAN JONES. The bizarre anachronism is part of the setting, and at worst I shake my head and smile as I go on.

Like the relay-based computer in the opening of Edmond Hamilton’s BATTLE FOR THE STARS. I know it was almost obsolete even when he was writing the story; but I am still enthralled, imagining the chatter as it guides the ship out of the way of FTL dust-grain collisions–and that chatter gradually rising to a continuous roar as they dive through a nebula and steering a safe course becomes ever more difficult.

Will they get through before the task becomes too great for the machine they depend on? Maybe.

Would the scene be improved by making the navcomp a modern piece of solid-state silent efficiency? Not a chance.

Would I write such a scene today? Of course not.

Does the march of time invalidate the story? I’ll answer after I’ve finished rereading TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA.

Well done, Misha!

Nice job