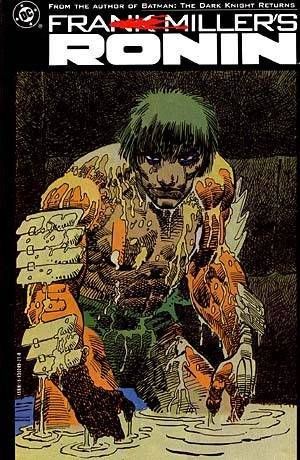

Coloring Outside The Lines: Frank Miller’s Ronin

Rōnin was written and drawn by Frank Miller, colored by Lynn Varley, and lettered by John Costanza. It was published by DC Comics as a four episode series, in 1983 and 1984, and collected into a single volume in first in 1987, then reprinted several times, including a deluxe hardcover, and a Kindle edition.

Rōnin was written and drawn by Frank Miller, colored by Lynn Varley, and lettered by John Costanza. It was published by DC Comics as a four episode series, in 1983 and 1984, and collected into a single volume in first in 1987, then reprinted several times, including a deluxe hardcover, and a Kindle edition.

So it is neither as obscure nor as difficult to obtain as my usual “Appendix X” choices, but I think it is worthy of a closer look as a literary work. Much has been written about the artwork and the graphic design, which was groundbreaking when it was published and continues to stand the test of time. Miller blended his own experience as an American comic artist with the very different style of Japanese comics to create a unique visual experience.

It certainly impressed me. I was not a comics reader when it came out, although I had friends who were. They had tried several times to get me to accept graphic novels as a legitimate artform for an adult audience, but nothing I saw made me think that comic books could be anything more than kid’s stuff—until Rōnin.

However, while it was the artwork that drew me in, it was the words that kept me going. The story was amazing—it wasn’t just a good story for a comic book, it was a good story, period. That is what I’d like to discuss.

Let’s pretend for a moment that Rōnin had been written and published as a text-only novel. Obviously much would be lost, and it would be a very different work. The story, however, would still stand and I believe that it would stand among the finest of traditionally structured novels.

We open with a sequence that is solidly fantasy. The setting—medieval Japan—is one that is exotic to most American readers, but the story is straightforward enough. A young samurai and his lord are traveling through the countryside when they are attacked by warriors sent by the lord’s enemy, a demon named Agat. The lord stole the demon’s magic sword. In a fairly painless expostulation dialogue, the lord explains that Agat is a shapeshifter, and that the demon’s sword drinks blood—the blood of evil men gives it power to protect the wielder from magic, but it takes the blood of a good man to give the sword enough power to kill demons.

All of these points become significant later on.

Shortly after this conversation the lord is killed by the demon, who had taken the form of a geisha in order to get close to his target. The young samurai becomes a ronin, masterless mercenary. The ronin takes the magic sword and flees, to wander the world and hone his skills until he is powerful enough to avenge his master by killing Agat.

And then we’re in the 21st Century, and we learn that the prologue was a dream. Billy is a quadriplegic, working for the Aquarius Corporation as a tester for prosthetic limbs. He has been having troubling dreams about long ago people and things that he doesn’t understand. His only friend and companion is Virago, an artificial intelligence. Virago has been searching for information to explain Billy’s dreams, and discovers a news story regarding the discovery of an ancient Japanese sword of unusual construction.

All of this setup is handled rather better than the way I am laying it out. The plot is complex, but the essence is that the spirits of Agat and the ronin were trapped within the magic sword, and when the sword was accidentally destroyed the spirits were freed. The ronin’s soul is drawn into Billy’s body, while Agat possesses the body of Taggart, the owner of Aquarius.

So that’s the story—a demon and a warrior from medieval Japan transported to a very dystopian 21st Century New York, battling to end their centuries long conflict once and for all. Right?

Well, it’s a little more complex than that, in the way that the Pacific ocean is a little more wet than the Gobi desert.

First off, there are some wonderful supporting characters with their own lives and their own stories, who are impacted by the main storyline in ways that are simultaneously unexpected and realistic. There is a surprisingly deep romantic subplot, and a world that is much more real than the usual cardboard cutout of a post-apocalyptic savage city in ruins.

Then we come to chapter six. Well, okay, the big twist comes at the end of chapter five—the fifth issue, when it was being published originally. In a scene worthy of Philip Dick, one line of dialogue changes everything. Miller basically takes everything that you think you know, puts it in a shoebox, and runs a steamroller over it.

Suddenly the reader has to reexamine the whole story to date in the light of the new information. Who the characters are, what their relationships are, who is a good guy, who is a bad guy—the last chapter becomes an entirely different kind of story.

And it works. That’s the crazy thing. Unlike the usual twist ending, this one actually takes into account everything that has happened in the first five chapters. If you go back and reread the whole story, knowing how it will end, it is still a damned good story.

It’s just not the story you thought that you were reading the first time through.

Okay, I’ve probably already said too much. I don’t think that I’ve actually given any spoilers, but I’ve let slip that spoilers do exist, and maybe that’s as bad. In my defense I will point out that I am talking about something that was published thirty years ago.

Also, I don’t see how it’s possible to explain just how good this story is without explaining what it does. Setting up a reader’s expectations and confounding them without breaking the suspension of disbelief is about the most difficult trick an author can pull off, and Miller does it here while making it look easy.

If you like comic books (or graphic novels, if you want to use the more accurate term) you are probably already familiar with Rōnin—you’ve at least heard of it, if you haven’t read it. If you don’t, you should check it out. The words+pictures format can take some getting used to, but the story will drag you in.

Trust me.

This is the Twenty-First Century, gentlemen. Try to keep an open mind.

—

Misha Burnett is the author of Catskinner’s Book, Cannibal Hearts, The Worms Of Heaven, and Gingerbread Wolves, modern fantasy novels collectively known as The Book Of Lost Doors.

What’s happened to Miller is truly sad. It’s especially bad how it’s affected his legacy. Miller should be remembered as perhaps the greatest writer of comics of all-time, but thanks to things like “All-Star Batman and Robin” he’s become a punchline.

It’s really quite sad, because when he was in his prime he was the master of masters.

“Ronin” was amazing! I never cared for the art style, so if that bothers you, don’t let it put you off, the story is excellent!

I submit that Miller’s reputation in the comics industry suffers more due to his being smeared as a “facist” by jealous lesser talents than any one subpar work. He was roundly reviled by the “right people” because he dared to write “Holy Terror” – where a superhero fights Islamic terrorists – for example.