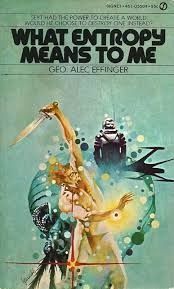

Guest Post by Misha Burnett: What Entropy Means To Me by George Alec Effinger

Monday , 28, March 2016 Appendix X 1 Comment Planet Of Weirdness: George Alec Effinger’s What Entropy Means To Me

Planet Of Weirdness: George Alec Effinger’s What Entropy Means To Me

Lacking the ox-stunning heft of, say, VALIS or Gravity’s Rainbow, George Alec Effinger’s What Entopy Means To Me, originally published in 1972, nonetheless stands as a giant of what might be termed the Literature of the Uncertain.

It’s a difficult work to describe without making it sound dull and self-important, and it’s neither. While it works on several levels, the most obvious and accessible one is that of slapstick parody. It’s a deliberate satire of message fiction. Imagine the Mad Magazine version of Pilgrim’s Progress. When I start throwing around fifty cent words like “epistemological” remember that I am talking about a book that features the protagonist being menaced by giant feral radishes.

So what’s the story here?

Well. That’s a good question.

We’re not on Earth, we know that much. This world (called, simply, “Home”) was colonized by a man and a woman. They are called Father and Mother. How, exactly, they ended up on Home is not clear, although the implication is made that they were fleeing debt collectors.

Father and Mother had a number of children. The eldest of these is a young man called Dore. As the story opens Father has been missing for a long period of time, Mother sits on the lawn and cries continually, and Dore has just been sent on a quest to go down the river of Mother’s tears to find Father.

The second oldest brother, Seyt, has been given the task of chronicling Dore’s adventures on the quest to find Father. Seyt, however, is not going with Dore—he’s staying at home and has no idea what actually happens to Dore once the oldest brother is out of sight down the hill.

So Seyt just makes things up.

Now, Seyt’s task is complicated by the fact that his work is continually being read by the other siblings, who examine the tale carefully for signs of deviation from an obscure orthodoxy. While everyone knows that there is no way to tell the story of what is really happening to Dore, there are multiple conflicting theories regarding what should be happening to Dore.

It is possible to see this novel as a metaphor for a great many things; religion, politics, science, literature, phenomenology, fire/life safety code enforcement, the phantasmagorical destination of those socks which go missing in the dryer. If Effinger ever revealed any deeper meaning to What Entropy Means To Me it wasn’t in any interview that I’ve read.

Nor does it matter. The satire doesn’t point fingers at this or that group, rather it invokes a sense that on some fundamental level the universe itself is broken and can’t be fixed. It is, at heart, an existential novel, while managing to avoid the usual pitfalls of existential literature. The clever use of a multilevel narrative—stories within stories within stories—allows the narrator Seyt to moderate the tone.

There is a lot of humor in this book. Effinger’s humor always has a kind of a ragged edge to it, though, as if his laughter could cross the line into hysteria at any moment. I would not, on the whole, call it a humorous book. Compelling, and enjoyable, yes, but not humorous.

Neither does it descend into soul-crushing nihilism. Rather it skates between the twin precipices of flippancy and despair, and does so adroitly.

This is a book which will make you think if you let it. In that it represents, for me, the best that the New Wave had to offer.

—

Misha Burnett is the author of Catskinner’s Book, Cannibal Hearts, The Worms Of Heaven, and Gingerbread Wolves, modern fantasy novels collectively known as The Book Of Lost Doors.

Please give us your valuable comment