Henshin! (A brief history of Japanese SF – Part 3 of 3)

Thursday , 2, March 2017 Uncategorized 13 Comments

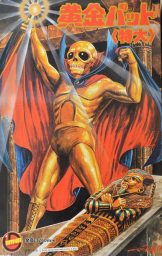

A fairly modern depiction of the Golden Bat, from the front of a collector’s model set box.

Last time, in Denki Jidai, we followed the transformation of Japanese genre fiction through what might be seen as a kind of “industrial revolution” – from the Meiji era on, Japan was absorbing and adapting Western technologies and ideas at a breakneck pace, and by the 1920s and 1930s hunger to catch up with the Western powers and take a place on the world stage had led to the import and translation of a variety of major Western writers.[1]

As the new technologies – particularly medical sciences and electrification/radio – exploded into the public consciousness, so too did technology start to play a larger and larger part in the adventure and mystery stories that were so popular. Domestic authors like Yokomizo Seiji, Kosakai Fuboku, and especially Unno Juza were pushing the art of fantastic fiction into the public view, blending the shocking implications of the new technology with the drama and excitement of murder mystery and adventure.

But it’s really what came next, after the shattering social and intellectual impact of World War 2 and the reality of the Bomb, that really sparked the amazing evolution of Japanese fantastic fiction in the following decades. So come with me now to trace the three pillars of that transformation: Henshin![2]

World War 2 had an unquestionable impact on what came of these trends in the following years of course, but to really understand the radical transformation of Japanese fantastic fiction and its evolution into multiple streams in the 1950s and onward, we need to jump back again to the early 1930s for a moment to the birth of the first superhero in the kamishibai.[3]

While in the West cheap pulp magazines and comic books were pouring into the masses and driving a vibrant literary entertainment industry, Japan had the twin problems of common illiteracy and the challenges of applying typesetting to the complex characters used to write Japanese. As a result, the old streetside storytelling and entertainment tradition continued with painstakingly hand-painted panels – and it is here, in particular, that the truly fantastic started to seep into genre fiction in Japan, I think.

And you can certainly see the collision of the Western adventure/mystery fiction that was so popular with the rise of: The Golden Bat!

Ogon Batto (The Golden Bat) first appears on Tokyo streets in 1931[4] as a creation of Nagamatsu Takeo, striking out with the powers gained during a mystic encounter in Egypt to right wrongs and defend the weak – all the basic elements of the early fantastic heroes are there: we have occult powers, we have strange and horrifying villains[5], we have the defence of noble ideals, we have peril. An interesting aspect of the Golden Bat is the way in which exotic Western characteristics are grafted onto what might otherwise be a standard Japanese “jidai geki” (period drama) hero to make him more fantastic – in direct opposition to the way things like kung fu and jujitsu were being deployed in the West.

Golden Bat was just one of the first of course, but kamishibai stories remained hugely popular through the 1930s and into the War, and continued to be an important medium for entertainment and information even into the 1950s, when it was eventually displaced by television and the availability of cheaper printed media in the form of mass market manga.

While comics certainly played an important role in Western fantastic fiction genres, I really don’t think it can be understated how integral the kamishibai and their manga successors were to the Japanese markets. The role of manga cross-overs, spin-offs and others in driving continued interest in print and visual medias is in many ways much more powerful than in the West, as we will see.

Moving back forward again, pure text remained a major force in the development of fantastic fiction of all kinds in Japan – not just science fiction. As we saw in Iron Tengu, Bamboo Girl, Japan actually has a long history of native fantastic fiction and this tradition fed into efforts by authors such as Edogawa Rampo[6], Okamoto Kido, and Tanaka Kotaro[7] in the 1920s. The weird tales of Japan’s 20s and 30s was beginning to split from science fiction per se in this era – but there was still strong cross-pollination between the branches, as we can see in strange tales such as Unno Juza’s “The Infrared Man” which, though ultimately a science fantasy detective story, leans heavily on the evocation of a sense of paranoia arising from the idea of an invisible, parallel biology and its potentially hostile denizens.

This brings me back to Unno Juza again, and for good reason:

Unno Juza’s early work was very much rooted in the traditions of Sherlock Holmes stories and the other “scientific detective” tales that were such a strong influence on his first works. But starting in the 1930s – and perhaps not coincidentally at the same time as Japan’s slide into fascism – Unno Juza’s work started to verge in new directions, marked by increased criticism of the social risks of modernization.

As I mentioned previously, Unno Juza was ultimately seconded into the Japanese propaganda machine during the War. Although he produced a number of light, educational pieces as part of this work, he continued to write under his usual pseudonyms with subtle criticism of the authorities and the direction he saw society moving. Little wonder then that when his work took him to sea and to one of Japan’s bloodiest Pacific battles his terrible experiences changed the tone of his work. And of course, along with many other Japanese artists and writers, the events of August 6th and 9th in 1945 were seared into his consciousness.

The collapse of the Japanese industrial fascist state of the War era along with the shock of science fiction made reality changed the character of Japanese print SF for some time to come. There was still to some extent a love affair with technology, but for a long time the genre was dominated by darker work that brooded on the consequences of technology – particularly in its use as a weapon or as a tool of oppression – and on world ending apocalypse. A powerful example of this era’s work is Kobo Abe’s novel Dai-yon Kampyoki (Inter Ice Age 4)[8] published in serial format from 1958 to 1959.

But really, for the next two decades print SF in Japan was again dominated by Western imports – mostly American, via the occupying forces – with only the abortive domestic SF magazine Seiun in 1954 as an effort to revitalize.

Popularity revitalized in the 1960s however, with the launch of a successful prozine Hayakawa SF Magazine, in 1959.[9]

In many ways, Hayakawa Publishing Corporation was a powerful force in genre publishing in Japan even before this magazine – they were founded almost immediately after the war and for many years were mainly turning out translations of American periodicals such as Ellery Queen Magazine, which they took on in 1954. Hayakawa SF, though was a new beast and it drove new interest among the SF-oriented authors of the period with its story competition, launching the careers of several major names, including well known authors such as Hoshi Shinichi, Komatsu Sakyo, Tsutsui Yasutaka and others.

These authors were certainly in many ways a product of the War – they were born just as the country was moving into a truly imperialist mode, and were in most cases just old enough that the events and impacts of the War would have been a major part of their lives. No wonder, then, that their work tends to focus on satire and social commentary as much as on speculation on the future and on the implications of technology.

It wasn’t all grim social commentary of course: as mentioned, the manga industry was booming and the 1950s and 1960s saw the launch of some very successful science fictional lines, mainly aimed at children – things like Doraemon and Astro Boy are perhaps the best known outside Japan, but any number of short-lived stories that revolved around children and their relationship with anthropomorphized technology (usually in the form of robots and wonderful gadgets not far removed from magic) were launched over the years.

And of course the social and political commentary wasn’t always grim on the adult end of things either – let’s not forget that the 1950s and the 1960s were the era of Godzilla and a multitude of other monster movies. To some extent, both film and television entertainment was largely aimed at youth in Japan through much of this period, however, so even here there was a strong weighting toward children, and for a long time SF was dismissed as “kids stuff” unless it was very literary.

So what changed?

About the same time that Donald Wollheim was transforming American SF first with Avon and then with his own DAW imprint of inexpensive paperbacks, Hayakawa Publishing pumped life into the scene and changed everything.

As mentioned, Hayakawa had been around for a while – the company had actually been established in 1935 as a mom and pop type business publishing a variety of minor items, mainly contract printing. They produced pamphlets, the occasional comic or magazine, and sometimes a cheap reprint of translated literature in formats similar to the “Penny Dreadfuls” that were seen in Europe.

The war had a chilling effect on publishing in general of course, since the government was taking as much control of communications as it could, but with the end of the Pacific War in August 1945 the company was established formally to serve the new market for imports – both translations and domestic work based on imported ideas that came with the American occupation. The enterprise was successful enough that by 1947 it had transitioned to being a full “kabushiki” or traded stock company.

By the 1950s, Hayakawa was specializing in imports, and the items that were gaining the most traction were – as we might expect – the pulps: along with Ellery Queen, Hayakawa took on all sorts of projects through the 1950s, and the appetite in Japan for more “adult” science fiction was so strong that despite the previous failure of domestic SF magazine Seiun[10] the company decided to launch its own magazine in 1959. Headed up by legendary editor and translator Fukushima Masami, this magazine launched the beginning of Hayakawa’s dominance in Japanese SF publishing.

Through the 1960s, Hayakawa’s three pronged attack on the market (contest, magazine, novel line) pressed SF deeper and deeper into the Japanese consciousness. Between the selective translation of great foreign offerings and the discovery of new domestic talent whose enthusiasm was bubbling at boiling point for the promise of the future it can justly be said that Hayakawa Publishing was the major driving force of SF in other venues as well, and the 60s and 70s is when things really took off.

The classics of the 70s in particular are an interesting era – this is when Japanese industry and society were exploding onto the world stage, and the Japanese entertainment industry (including publishing here) was just as busy remixing and cross-pollinating as the rest of the country. From classic anime titles like Gatchaman[11] and Cutie Honey which follow the typical Japanese formula to straight mutations[12] of Western classics like the Heidi series and Battleship Yamato[13] the ideas and themes were bounding back and forth, evolving, growing. Changing into something new and exciting.

And a major force feeding into this evolution was again Hayakawa. Again and again they proved to have a deft hand in selecting not only the bright new stars of the Japanese scene – people like Komatsu Sakyo (Virus: The Day of Ressurection(1964), Japan Sinks (1973), The Savage Mouth(1978)[14]) – but also injecting the serum of greatness with new or revised translations of Western stories ranging from the best of the 1920s and 1930s (including reprints of Merritt, Brackett, Kuttner, and others) to more recent fare by the stars of the Campbell revolution and the New Wave.

An excellent example of this is Gundam – launched in 1979, the franchise exploded immediately and is still an enormous business today. Watching the show, you would be right to wonder about the relationship between the Gundam mobile suits and the mobile infantry of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers – in fact the creator, Tomino Yoshiyuki, has said explicitly that the book was a major influence in the development of his ideas. It is no coincidence that Hayakawa republished their translation as part of their new SF series in 1977.

Perhaps most illustrative of this is the Japanese take on superheroes.

Back at the start I touched on Ogon Bat – arguably the first superhero – and his place in kamishibai. Japan’s rapier-wielding Batman stayed the course and in fact still has a following today, but even more interesting is what happened when Japanese SF media producers noticed the success of heroes on the screen. The result? The birth of Japan’s own crop of heroes.[15]

Largely rooted on the small screen, Japan’s costumed heroes are a subject big enough to make a series of posts of their own, but I think that they are a perfect illustration of the way that in Japan manga, anime, small screen, big screen, and traditional print intertwine to create entire ecosystems of fandom. Not to mention the multitude of ways in which they intertwine among themselves and create bizarre offspring in new stories.

From Ultraman and Star Man, through the various sentai teams, and on to Kamen Rider, these live-action heroes blend the flash of high technology with mystical powers and a dizzying array of bizarre creatures through their “monster of the week” formula. But although the shows are superficially simplistic fluff, they often tackle quite sophisticated story arcs and deep ideas: don’t be fooled by the schtick of a creature animated from a washing machine or other mundane object, there’s meat in there and layers that aren’t always obvious from a single episode.

And this is true when we come back to print again: Japan has a dynamic “light novel” market that is constantly discovering new talent and publishing new lines. From heavy classics like Tanaka Yoshiki’s Legend of the Galactic Heroes series and Ohara Mariko’s Hybrid Child through lighter comic fare such as the Slayers series by Kanzaka Hajime Japanese SF continued to grow and evolve through the 1980s and 1990s.

With the evolution in the 2000s, things have headed into high gear and it is no longer even remotely possible for me to follow what is happening here. Although Japan was late to the ebook game, the explosion of web comics in the early 2000s was matched in Japan by an explosion of micronovels and serials published via cell-phone email. Meanwhile, machine translation is speeding the import of cheaper Western translations, and Japanese versions of recent Western fare is more readily available than ever.

With the new push by Amazon and Kobo into ebook platforms over the past 5 years, and at last cooperation from the publishing industry (whose resistance was a huge factor in the resistance to adopting ebooks more generally here) there has been an explosion in self-publishing and in micro-publishers in the market. As one might expect from the history of genre fiction when it comes to new media, science fiction and fantasy are very much at the forefront in this market, and it is exciting to see the whole range of options flooding the pages.

Japanese SF is on the verge of a transformation now, and the next 5 years are going to be incredible.

HENSHIN!

—

[1] I think it’s probably important to note that these imports were by no means only English – French, German, Dutch, and other writers were getting into the magazines and newspapers as well, a significant difference from what was happening in the North American scene.

[2] The traditional cry of the Japanese hero as he or she transforms!

[3] Although public education, based on European models, was making strong inroads in Japan during the early decades of the 20th Century, literacy was still a challenge and of course the simple cost of luxuries like printed media was a barrier outside the educated middle class. Luckily, Japan had a tradition of travelling storytellers and street performance that made a perfect foundation for kamishibai or “paper entertainment”

Japan has long had a love of storytelling via images, with satirical cartoons and illustrated stories reaching back centuries – and of course the format was also frequently used for education by Buddhist monks, an approach coopted by the government both for public education and news, and of course for propaganda. But here we are most interested in what was happening in the depression era cities of Japan.

[4] Predating fellow Japanese hero Prince Gamma by a year or two, and trumping the West’s foray into illustrated super-heroism with Superman and Batman in 1938 and 1939 respectively.

[5] None, perhaps, quite so horrifying as the villain of this live action movie adaptation of the Golden Bat from 1966… Though not quite in the sense I meant it!

[6] As with many Japanese authors, Ranpo’s pseudonym is a deliberate play on words, in this case an echo of Edgar Allan Poe, whose weird fiction was a major influence.

[7] Who were building on the body of work already well established by the 1920s and 30s, reaching back in reasonably modern form at least as far as Ueda Akinari’s story “The Chrysanthemum Pledge”

[8] Often considered the first full-length Japanese SF novel

[9] The first issue was actually January 1960, but Japanese periodicals typically distribute the month prior to the cover date.

[10] Which only saw a single issue before disappearing – but holds place of pride as the origin of the Japanese SF award. The failure of this magazine is curious, considering the strong lineup (Heinlein, Merritt, Neville, and Japanese authors like Kayama Shigeru and Suzuki Yukio who were prominent right through to their deaths in the 1970s)

[11] Maybe better known as Battle of the Planets or G-Force in the West.

[12] I hesitate to call them adaptations since, if we’re honest, they bear only superficial resemblance to the original material.

[13] Originally intended as a riff on Lord of the Flies!?

[14] Which made such a splash that it was translated by Judith Merril!

[15] And one of the reasons Marvel, DC, and the others have had such a hard time getting traction in Japan until very recently.

I was actually hoping you’d be able to go into modern jp lit more, with the crazy web novel structure it’s taking, and the LN-manga-anime complex where you don’t know if your names-changed-fanfic might become the next big thing. It seems inherently democratic, and so of course inherently chaotic. I guess nobody knows very much.

-

I guess this also makes it incredibly hard to discover worthwhile SF or horror there, and as always popularity needn’t indicate quality.

Which is, I suppose, why there doesn’t seem to be much discussion about it over here.-

That’s certainly part of it – as is accessibility (you really can’t even see it unless you’re in Japan) and of course the language barrier.

-

Fascinating post! Props for the soutout to Wollheim, who still doesn’t get the credit he deserves. From what I’ve read, Derleth’s Mythos fiction made it over to Japan fairly early, setting the template there.