Heroines, Then and Now

Saturday , 9, September 2017 Appendix N, Authors, Before the Big Three, Fiction 20 Comments

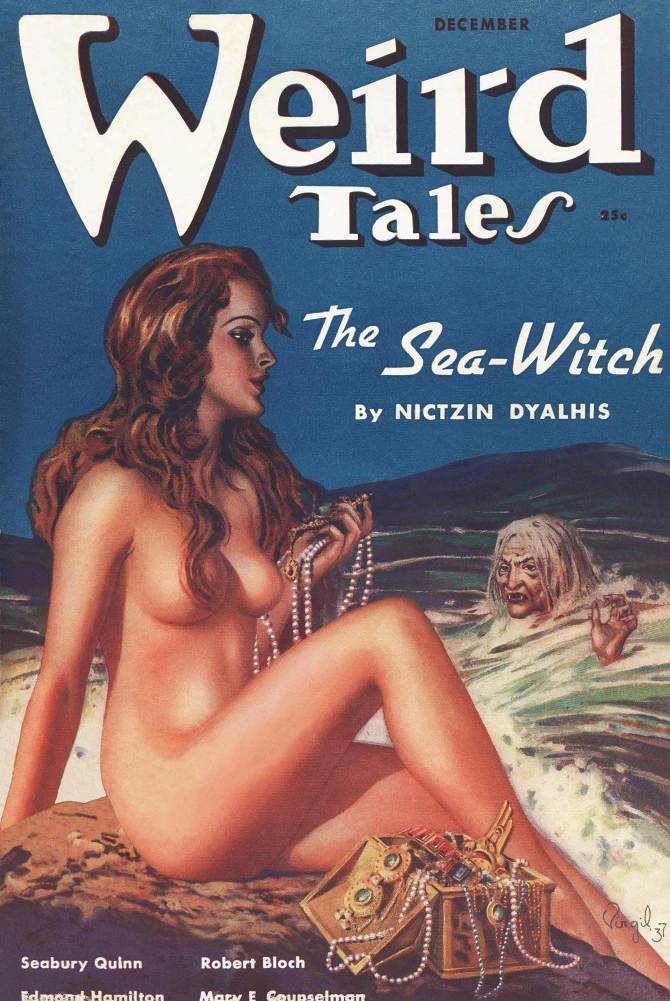

A damsel being threatened by a modern-day “strong female protagonist”!

A frequent criticism of older stories, pulp or otherwise, is that they feature a “damsel in distress”. That the woman in question is nothing more than a prize to be won. This is considered bad, and earnest leftist writers of today seek to correct this horrible injustice by creating “strong female protagonists”.

Right away, one notices that having a “strong female protagonist” would be a bad idea given the nature of many stories. The women in Howard’s Conans were not unique or terribly interesting, but neither was any character outside of Conan. He is the only exceptional one. This is by design; no matter what magical powers they had, or how exotic their description, no other character outshines the main star. Trying to create a heroine who does that would be awful and counter-productive, lessening the appeal of the protagonist and his adventures. In fact, this is what a great many Hollywood action movies nowadays do, and it’s one reason they fail.

Still, let’s compare some female characters from older stories to those of today.

A lot of female characters, even in pulps or adventure tales, were very far from any kind of “damsel”. However, let’s consider those that did need saving or considerable help from gallant, daring men. One immediately sees considerable variance in their personalities. Some are delicate, while others are tough. Some are meek, while others are strong-willed. Some are stupid or at least lack guile, while others are devilishly smart or inscrutable.

For instance, I’ve recently been reading Sabatini’s The Snare, which illustrates this well. On the one hand, you have Lady O’Moy, a beautiful, haughty idiot who can’t stop herself from being a blabbermouth;

Now if you have understood anything of the character of Lady O’Moy you will have understood that the burden of a secret was the last burden that such a nature was capable of carrying. It was because Dick was fully aware of this that he had so emphatically and repeatedly impressed upon her the necessity for saying not a word to any one of his presence. She realised in her vague way—or rather she believed it since he had assured her—that there would be grave danger to him if he were discovered. But discovery was one thing, and the sharing of a confidence as to his presence another. That confidence must certainly be shared.

Lady O’Moy was in an emotional maelstrom that swept her towards a cataract. The cataract might inspire her with dread, standing as it did for death and disaster, but the maelstrom was not to be resisted. She was helpless in it, unequal to breasting such strong waters, she who in all her futile, charming life had been borne snugly in safe crafts that were steered by others.

Then, however, you have her cousin Sylvia Armytage, a beautiful, brave, intelligent woman capable of concealing her emotions exceedingly well;

Miss Armytage without any of Lady O’Moy’s insistent and excessive femininity, was nevertheless feminine to the core. But hers was the Diana type of womanliness. She was tall and of a clean-limbed, supple grace, now emphasised by the riding-habit which she was wearing—for she had been in the saddle during the hour which Lady O’Moy had consecrated to the rites of toilet and devotions done before her mirror. Dark-haired, dark-eyed, vivacity and intelligence lent her countenance an attraction very different from the allurement of her cousin’s delicate loveliness. And because her countenance was a true mirror of her mind, she argued shrewdly now, so shrewdly that she drove O’Moy to entrench himself behind generalisations.

Quite an interesting contrast, and it lends the novel a distinct flavor. (In fact, the idea of a worthy damsel and a lousy one occurs in Scaramouche, too) Thus, one sees there is considerable complexity and difference between such heroines, even when they’re not meant to outshine the hero, or be the central focus of the work.

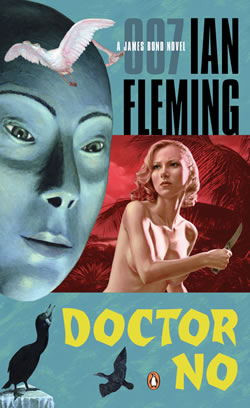

An okay attempt at conveying Ryder’s look, but it’s lacking the broken nose.

And even supposedly lowbrow works can have surprising, unique heroines that subvert the standard sequence of affairs. Consider Honeychile Ryder in Ian Fleming’s Dr. No. Here is how I described her in a review of that book;

“Honey Ryder is easily the best heroine Ian Fleming ever created.

She is tough, brave, beautiful, independent, and intelligent, without ever becoming a caricature or unrealistic. In fact, as much as I love Ursula Andress (one of the sexiest women of the 1960s) and her on-screen portrayal, I prefer the book version even more. Here, in her famous scene on Crab Key, Honey isn’t just wearing a bikini; she is completely naked, with only a belt holding a knife on it.

It’s an important distinction, not just for the comparison to Boticelli’s Venus, but because throughout the book Honey is depicted as primal, direct, and unashamed.

Another major difference is that despite being perfect otherwise, Ryder has a badly broken nose, suffered when a white plantation overseer punched her out and raped her as a teen. Honey’s response to this is to calmly go to a doctor to make sure she is not pregnant, and then kill the man in a particularly tortuous, slow manner.

Then, upon meeting Bond, and caught in a sudden explosion of violence she has never experienced, Ryder keeps her composure, bravely resisting throughout. Without spoiling it, she also completely outwits Dr. No, a man depicted as an evil, brutal mastermind. This leads to an amusing scene where Bond rushes to save Ryder, only to learn she needs no saving at all, having escaped by her own powers.

Later, she refers to the main antagonist as nothing more than a silly man.

I could go on with further examples (I also like how sexually aggressive she is), but suffice to say Honey is one of the coolest, best heroines I have come across in the entire action/adventure genre, nevermind just the Bond series. She is brave, tough, and intelligent while still being distinctly feminine, instead of a macho male character given a different set of genitalia. (Like most movies and book that want to create a “badass” female lead and fail at it miserably)”

On an amusing note, how do you think SJW and feminist reviewers react to this genuinely strong, independent heroine in their own reviews of Dr. No? Why, by denouncing her as awful sexist eye candy, of course! (Which serves to show how useless it is to ever believe SJWs or try to satisfy their professed desires)

Now, let’s compare these interesting characters to heroines of today. Frankly, it’s hard to come up with specific examples. They’re all a bunch of nameless, faceless, interchangeable golems with female exteriors. There is, however, nothing feminine about them.

Annoying, stupid little girl murdering entire kingdoms (the Freys) by herself? Sure, why not!

They are, however, far more ridiculous and absurd than any traditional damsel. This is because modern works make their heroines better, stronger, smarter, braver, and more competent than any male character. Increasingly, they are perfect at everything. Consider Rey in the new Star Wars film. Or any major female characters in Game of Thrones outside of Cersei, Sansa seasons 1-6 (but not the most recent one), and Daenerys only in the first season. Do they have any flaws? No, not really. And they’re better at the men at endeavors which they have no right to be, such as Brienne of Tarth being arguably the best swordsman in Westeros and Arya being its greatest assassin. This is laughably idiotic for anyone who has ever played any sport seriously and observed the physical difference between men and women. (I could do an entire piece on the absurdity of women going toe-to-toe physically with men)

These are not even characters. They are a silly, foolish attempt at being paragons of perfection. They make the work impossible to take seriously, severely harming its effectiveness. (Indeed, what I mentioned is one of the biggest flaws in Game of Thrones, a good show I generally enjoy)

This of course applies to science fiction, if one considers any of the nauseating women John Scalzi writes, or those appearing in the works of other SJW hacks. As one can see, these newer, more modern heroines are not an improvement at all, but half-a-dozen jumping leaps backwards. In fact, I can’t think of anything worse than what they have concocted.

And one would do well to respect the female characters of earlier writers and pay attention to how they crafted them, damsels or not.

Great article. About 10 years ago I wrote a blog post about warrior chicks in sci-fi movies, one of my favorites being Sigourney Weaver in her “angry mama bear” battle scene in Aliens. None of the newer ones come close, especially not the ludicrous Mary Sue Rey. I have to disagree about Arya Stark, however, as admittedly annoying as she is. An assassin doesn’t require physical strength, just stamina, cunning, and ruthlessness, three qualities women do have.

Great post!

BTW, Sabatini’s THE SNARE is one of Rafael’s works that we know Robert E. Howard read.

The women from REH’s Conan stories provide a nice contrast with one of the most common–and irritating–mistake writers (especially screenwriters) make with female characters today.

In REH’s Conan stories, Conan’s feminine foil is often introduced in an unflattering light, and Conan is usually a jerk to her. Slowly, she shows her mettle and gains the respect of both Conan and the audience. This isn’t exactly formulaic–female characters do it in different ways across different stories. That keeps it fresh, and REH is very good at pacing the showing of mettle in a way that makes for a very effective arc.

Movies today frequently do almost the exact opposite! They introduce a female character as strong–perhaps only by the character insisting she doesn’t need the help of the main character–only for the writer to fall back on the lazy damsel in distress trope.

It is a bit of a stretch to call it a movie “today,” but Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves is a good example. Maid Marian is introduced by giving Robin as good as she gets with a long dagger. That fighting ability never appears again. She does play an active role in the plot afterward. But by the final act she is reduced to nothing but a damsel in distress. Her character arc runs in the wrong direction!

-

It’s almost like a female character is best served by character development, rather than objectification (the object in this case being “Kick Ass Grrl”. Note that while there are three or four ways of being a sex kitten or blatant eye candy, there is only one “Kick Ass Grrl” and she generally has no other emotional or personality traits).

I have absolutely no problem with a female CHARACTER being amazing at something, even something she ought not be expected to master; exceptional characters are a staple of fiction. But the current KAG isn’t a character, isn’t a protagonist, isn’t anything of interest to anyone.

I just love Skyvia’s characterization. You can almost imagine the blend of intelligence and beauty.

i plagarized parts of it and rewrote in Catalan. Very nice and I’m using it 🙂

One question what does clean limbed mean? First time i’ve heard of it and just don’t get it.

xavier

-

It basically means “buff/well-toned” or “not flabby”. A popular phrase in Anglophone fiction before WWII. Robert E. Howard and ERB both used it, IIRC.

As a bonus, “hawk-faced” means having a prominent nose.

Hope that helps.

-

A body builder would not be clean limbed. Might be buff but not clean limbed. Hawk faced often refers also to deep set eyes as well as a long or prominent nose.

-

This. Clean-limbed implied “athletic, but not muscle-bound–displaying the potential for both strength and grace.”

In the old days, cleaned-limbed was the preferred look. It’s no accident that, right up into the Sixties, Tarzan was almost always played by a swimmer. You only hired bodybuilders to play Hercules or the like.

-

-

Thanks very much for the definition of clean lumber.Hawk nose I’m more familiar with as It’s a synonym for aquline nose,

Always fun to see how languages change over time.

xavier

-

“And they’re better at the men at endeavors which they have no right to be, such as Brienne of Tarth being arguably the best swordsman in Westeros and Arya being its greatest assassin. This is laughably idiotic for anyone who has ever played any sport seriously and observed the physical difference between men and women.”

Well, Brienne of Tarth is supposed to be an unusually large and muscular, somewhat masculine woman who spent decades training in combat – definitely an outlier. Arya kills by speed, stealth, or poison, she doesn’t just somehow overpower experienced soldiers several times her size – in fact, they showed that specifically when she sparred with Brienne. The real problem with Arya (besides her being an obnoxious little turd) is that her abilities don’t really seem earned: yes, we saw her learning how to fence, and she lived with the Faceless Men; but her apparent extremely-high level of skill, despite leaving Braavos early in her training, doesn’t really make sense. I’m starting to wonder if the fan theory about her being killed by the waif, who is now wearing her face, is true (despite that not making much sense itself).

Well, I found the Devi, Belit, and Valeria of the Red Brotherhood all unique and interesting, so I guess this is YMMV.

As far as modern stuff goes, no one is–male or female– is as much of a bad ass as Kate Daniels in the series by Ilona Andrews. She doesn’t bother taking names, just lives.

The women in Howard’s Conans were not unique or terribly interesting” – well, that pirate queen (I can’t recall her name right now) might not be the most ‘unique’ character in fantasy, but at one point she became equally important as the Cymmerian himself.

In over 10,000 newspaper comic strips and ten prose novels & short story collections, Modesty Blaise is probably the best example of a kick-ass and take names female in the English language.

Please note that the film “Modesty Blaise” happened at the wrong time and got the Batman TV-series camp treatment. The novel of the same name & plot was written seriously.