This is a guest post by Richard who has contributed a few pieces before:

Edward Frankland’s Forgotten Masterpiece

There can be few people these days familiar with the work of  Edward Frankland (1884-1958). And even amongst this minority far fewer still will be conversant with his 1932 novel of Viking Westmorland entitled HUGE AS SIN. If Frankland himself can be said to have fallen into unwarranted obscurity over the years then it is no hyperbole to describe his novel as having all but evaporated from existence. Since the time a copy came my way by fortuitous circumstances I have yet to discover even one other being offered for sale anywhere. And as Thor and Odin are my witnesses I have looked hard enough. It is bad in itself that Frankland is being deprived of a readership and acclaim that he merits but the rarity of HUGE AS SIN is doubly regrettable because, in my estimation, it is nothing less than a lost masterpiece.

Edward Frankland (1884-1958). And even amongst this minority far fewer still will be conversant with his 1932 novel of Viking Westmorland entitled HUGE AS SIN. If Frankland himself can be said to have fallen into unwarranted obscurity over the years then it is no hyperbole to describe his novel as having all but evaporated from existence. Since the time a copy came my way by fortuitous circumstances I have yet to discover even one other being offered for sale anywhere. And as Thor and Odin are my witnesses I have looked hard enough. It is bad in itself that Frankland is being deprived of a readership and acclaim that he merits but the rarity of HUGE AS SIN is doubly regrettable because, in my estimation, it is nothing less than a lost masterpiece.

The setting for the book is Frankland’s adopted county of Westmorland during the third quarter of the 9th Century. The story is placed against the historical backdrop of the Danish invasions of Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless, and with the wars of hegemony waged in Norway by Harald Luva. Each of these events exerts its own gravitational influence upon the story but this is not a novel of great men and great happenings. Instead it is a largely provincial affair of one man’s personal ambition.

The hero of the novel is a Viking raider by the name of Thorolf Arnvidson, a man who dreams of carving a kingdom for himself out of the fells, becks and dales of North West England. In pursuit of this end he massacres an entire English clan by burning them alive in their own hall. But when his own followers are wiped out almost to a man in a reprisal ambush Thorolf finds himself reduced to the status of a wounded fugitive sheltered by a Welshwoman in her hovel. From this nadir in circumstances the book follows Thorolf’s fortunes as, undaunted, he sets out in renewed pursuit of his ambition.

Thorolf develops over the course of the ensuing months and years  into a complex and compelling character. He is described as having “the gloomy splendour of a man marked out by fate for mighty deeds and shifting fortune”. Unlike the majority of the men he comes to surround himself with he is conscious of the strange dichotomy that invests the Vikings of this period with both greed for the land of others and the onus to then defend it against people identical to themselves. But he is also a man flawed by introspective torpors, dawdling when the situation demands urgent action: “Is a kingdom to be lost for the sake of a girl?” he is reprimanded at one point by the girl in question.

into a complex and compelling character. He is described as having “the gloomy splendour of a man marked out by fate for mighty deeds and shifting fortune”. Unlike the majority of the men he comes to surround himself with he is conscious of the strange dichotomy that invests the Vikings of this period with both greed for the land of others and the onus to then defend it against people identical to themselves. But he is also a man flawed by introspective torpors, dawdling when the situation demands urgent action: “Is a kingdom to be lost for the sake of a girl?” he is reprimanded at one point by the girl in question.

Thorolf proves himself to be an essentially humane and far-sighted man by Viking standards. He comes to find more to his liking in the ways of the Swedes who “were content to have good things and use them” rather than with his own countrymen’s relish for wanton destruction. But he does not shirk from brutality when necessity demands it as seen when he hangs Bethoc, son of the king of the Strathclyde Welsh, amidst the sacrificial offerings on the midsummer blot tree.

Thorolf dominates proceedings and considerable emotional capital comes to be invested both in him and his fate. Frankland is far more frugal with the development of the supporting cast who are largely characterized in broad functional strokes. Only the sly and vicious Alkfrith, an English King’s step-son sired by an Irish thrall, and the Norwegian Spear Maid Thora, stalwart in purpose and possessed of the gift of prophecy, really stand out. But even the minor participants like the huge bareserk Arngeir Grettirsbane add their own distinctive dashes of colour to events.

Frankland was able to bring a variety of talents and personal experience to the writing of HUGE AS SIN, all of which contribute to its compulsive quality. He knew Scandinavia well for instance, spoke the languages and was possessed of a convincing insight into the Northern psyche. This equipped him to paint an authentic picture of a pagan society shaped by notions of luck and predestination and in which totems like the Shame Pole – capped by the rotting head of an ox – exert profound influence.

But Frankland was also a farmer and brought a countryman’s eye to the description of the Westmorland landscape, which he clearly loved and which is rendered in rhapsodic prose. The Scandinavian influence has left an indelible mark on both the topography and language of the region which persists to this day and Frankland was a man profoundly aware of that and in evident sympathy with it.

The book has a matter-of-fact attitude to the commonplace brutalities and violence of Dark Age life where the lot of women and servants was less than that of a horse “apt to go its own way if it grew aware of unspurred heels.” There is plenty of action and fighting – including a splendid and vivid recreation of the storming of the Rock of Dumbarton in 870 – but it does not wallow in gouts of blood and viscera. Instead of opening to the stroke of a sword cleaving bones to the marrow as a modern book would HUGE AS SIN beguiles the reader in much the same way as Thorolf himself is beguiled by the fells of Westmorland, drawing them further and further in until before they even realise it they are intractably absorbed in the narrative.

And it is an utterly captivating tale which successfully captures the tragic doom laden timbre of the sagas and which culminates in a powerful and affecting climax; one which, whilst it is hard to imagine any modern author choosing to follow, yet remains perfectly in keeping with the tone and temper established in painstaking fashion over the course of the entire book.

For all his equanimity and visionary virtues Thorolf is ultimately a victim of tradition. His commitment to the vow extracted from him by the Welshwoman Nest at the lowest ebb in his fortunes comes to assume an onerous weight as those fortunes wax in turn and eventually compels him to a compromise which whilst winning him much loses him the very thing he values most. Running in concert with this is the obligation of blood-debt which Thorolf is capable of dismissing intellectually as a ruinous and empty undertaking but which mists his vision with a red cloud regardless to calamitous consequence.

I have read a considerable amount of Viking fiction in my time but I cannot recall any I was ever so reluctant to finish. It is little less than criminal that this magnificent book should remain so stubbornly hard to come by. Should any reader chance upon a copy in their book browsing they should not hesitate to acquire it. Similarly if any enterprising publisher is in the market for a vintage Viking tale to reprint then they should not be looking any further than this one.

Only the certain knowledge that there is more of the same to come can ever provide a crumb of comfort at the finishing of an unputdownable book, which HUGE AS SIN most certainly is. Frankland did not produce a lot of historical fiction, and today whatever reputation he is still able to muster largely rests with his 1944 novel THE BEAR OF BRITAIN which was probably the first novel to tackle the Arthur story in realistic fashion. But as luck would have it in 1935 Frankland published a sequel to HUGE AS SIN entitled THE PATH OF GLORY. This book remains no easier to acquire than the majority of his others, regrettably. Happily those fortuitous circumstances that procured me the copy of HUGE AS SIN likewise delivered me a copy of the follow up too. It would be no chore for me to post something on this book also should anyone be interested in hearing about it.

“Similarly if any enterprising publisher is in the market for a vintage Viking tale to reprint then they should not be looking any further than this one.”

Well, that’s me! But I don’t know how I’m going to find a copy.

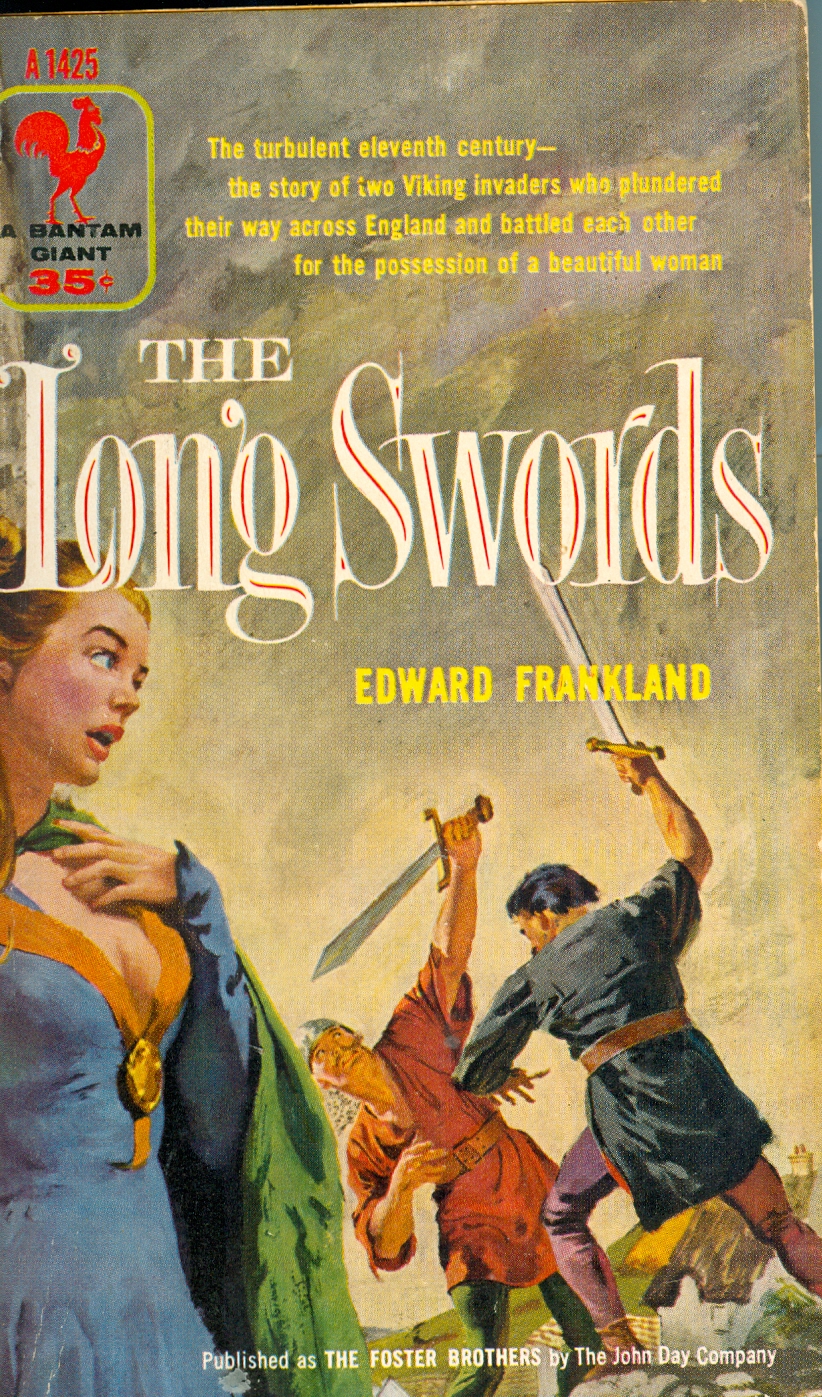

Have you read “The Long Swords?” Is that a good one as well?

THE LONG SWORDS is an excellent novel. It is possibly the only novel I’m aware of to have been issued under four different titles in little more than ten years. It first appeared in the UK as THE HALF BROTHERS. It then transferred to a US hardback edition as THE FOSTER BROTHERS before being retitled THE LONG SWORDS for paperback publication. Finally it returned to the UK as a hardcover called THE INVADERS in 1958, the year of Frankland’s death.

If you are serious in your interest I would be very happy to make the relevant enquiries to locate the current copyright holders. Frankland’s last surviving son only passed away in 2019 at the grand old age of 97.

-

I’m definitely interested, but I want to read the material first before making anyone an offer (assuming it’s not in the public domain).

-

Understood. It was only my intention to source the information; not to presume to open any sort of negotiation.

The copyright status of the book is unknown to me. Frankland has been dead less than 70 years. However the book was published by Jonathan Cape who no longer exist as an independent entity but only as an imprint of Random House.

Certainly read THE LONG SWORDS. HUGE AS SIN is superior, but it will still provide a useful barometer of Frankland’s qualities.

-

Thanks. I don’t know the ins and outs of UK copyright law, so I have some research to do.

I just ordered a copy of The Long Swords. I’m looking forward to reading it!

-

-

Now I would buy those two books if you ended up re-printing them.

Incidentally, for the benefit of anyone who has been wondering about the seemingly non-descript title of the novel, it is a quotation from Chesterton’s Ballad of the White Horse:

“And hairy men, as huge as sin/With horned heads, came wading in”.

“The story is placed against the historical backdrop of the Danish invasions of Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless,…”

For anyone interested in this era of history, I strongly recommend “Laughing Shall I Die, Lives and Deaths of the Great Vikings” by Tom Shippey, 2018. Chapter 4 is dedicated to examining the tangle of legend and history about Ragnar and his sons: “Ragnar and the Ragnarssons: Snakebite and Success”. Among other interesting details, Shippey argues that Ivar the Boneless’ nickname should be more accurately translated as “Legless” and understood as a reference to his claim of a dragon ancestor.

By the way, thank you for explaining the title since I found it puzzling. Also, it reminded me to find my collection of Chesterton’s poetry and reread “The Ballad of the White Horse”.

What about The Murders At Crossby. Any idea what that one is about?

-

Yes. THE MURDERS AT CROSSBY was Frankland’s last published book, appearing in 1955. It is another novel of Viking Westmorland but not one in the same vein as HUGE AS SIN or THE PATH OF GLORY. As the title suggests it is a murder mystery set in the year 942. As such it stands as a forerunner of the sort of historical whodunnits which are so popular these days. I do have a copy of the book but haven’t read it as yet. When I do I’ll be sure to post a review of it here.