Last time, we explored the idea of science fiction as an uncomfortable marriage between speculation and setting. And while the speculative predictions and the mythology of “What if?” have taken precedence within the SFF community, with every flip phone, tablet, defibrillator, and credit card celebrated, the gadgets, knickknacks, and tchotchkes–these elements of setting–are remembered when the adventures and mysteries that used them are forgotten,

Last time, we explored the idea of science fiction as an uncomfortable marriage between speculation and setting. And while the speculative predictions and the mythology of “What if?” have taken precedence within the SFF community, with every flip phone, tablet, defibrillator, and credit card celebrated, the gadgets, knickknacks, and tchotchkes–these elements of setting–are remembered when the adventures and mysteries that used them are forgotten,

Stories such as George O. Smith’s “QRM Interplanetary” are remembered, not for adventures and mysteries, but for the setting quirks. In “QRM Interplanetary”, the quirk was a space station that envisioned satellite communications and long-haul communications years before the U. S. Navy’s first experiments with the concept. Meanwhile, Arthur C. Clarke’s “Superiority” with its warnings against overconfidence and overcomplexity to generals, managers, and inventors, alongside other dire SFF tales of warning and woe, have vanished from the public consciousness, as decades of defense boondoggles and runaway spending have shown. Certainly, administrative error is far more abstract than satellite television, but it can be argued that the genre’s fixation on technological prophecy has trained readers to approach science fiction as a setting or an aesthetic to be mined instead of for the stories that take place in these settings.

But that is an argument for another time.

Instead, let us examine why setting is so vital to fiction, and science fiction at that. After all, critics are fond of saying that there are limited types of stories that can be told. And while these stories are viewed outside of their setting, how that story is told depends on the environment it is set in. A shipwreck story may have the same structure regardless of whether the shipwreck happens in the Arctic, the Tropics, the ocean floor, or Mars, but the tools, challenges, and demands available in space are different than in the Caribbean.

But that’s too academic for fiction. Instead, let me show the power of a setting through a story. A true story, of 1930s Hollywood, of a man born as Ernest Raymond Gantt. A man better remembered as The Beachcomber.

Donn Beach.

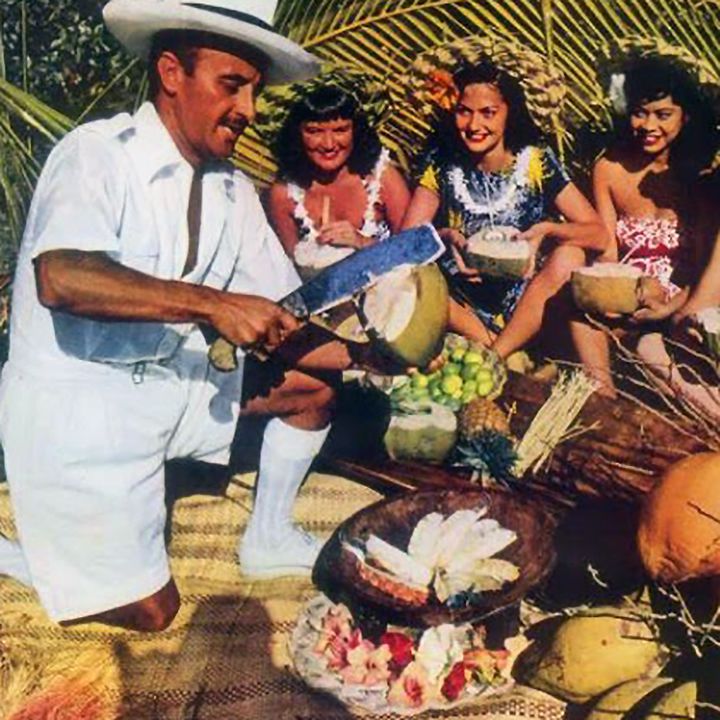

In 1931, Gantt returned from his youthful travels in the Caribbean and the South Pacific with a huge collection of memorabilia that could be, and, was featured as the backdrop for low budget movies. Soon after, Gantt opened his own bar where, alongside the showmanship flair of a Vincent MacMahon, he served a mix of California juices, Caribbean spirits, and Chinese food and slapped on a Polynesian overlay seasoned by whatever flotsam washed up. The result?

The Tiki bar.

Even in Hollywood, nothing quite like this had been seen before. Elegant, tropical-themed nightclubs like the Coconut Grove were well-known and offered luxurious fantasy to the swells in black tie. But this was something else–a little coarse, a little rough around the edges. One man’s vision of an island rum shack, from an island located somewhere between his left and right ears. — from Smuggler’s Cove, by Martin Cate.

The novelty was such that the stars of Hollywood noticed and made Donn the Beachcomber one of the prime nighttime spots of the 1930s, 1940s, and beyond. And Donn Beach spawned a legion of imitators, including his rival, “Trader Vic” Bergeron. This Californian amalgam of all the temperate islands spread across the United States, creating a popular form of dinner entertainment that lasted in its first burst of popularity for 40 years, even enshrined in his park by Walt Disney himself.

The novelty was such that the stars of Hollywood noticed and made Donn the Beachcomber one of the prime nighttime spots of the 1930s, 1940s, and beyond. And Donn Beach spawned a legion of imitators, including his rival, “Trader Vic” Bergeron. This Californian amalgam of all the temperate islands spread across the United States, creating a popular form of dinner entertainment that lasted in its first burst of popularity for 40 years, even enshrined in his park by Walt Disney himself.

The appeal to starlet and working man was the same, the space itself. A strange over-the-top mix of flotsam and palm fronds, flowers and Polynesian statues, leis and ladies. All designed to draw patrons inside and to the bar for Mai Tais, Zombies, and a host of slings, swizzles, and daiquiris. Enough for a Missionary’s Downfall, or to make a Suffering Bastard in the morning.

These drinks gave you the sensation of being somewhere else. Somewhere quite far away from your mundane home or your humdrum job. Somewhere…exotic. It was how the ingredients came together, how the drinks were presented–in a coconut, in a cove of ice–and what they were called that set the stage. No one in Sumatra, Rangoon, or Tahiti really drank anything like this, but no one could afford to visit these places to find out the truth. — from Smuggler’s Cove, by Martin Cate.

The emphasis is mine, and let’s add Hawaii to this list. For in the years after World War II, with Hawaii rapidly shifting from territory to state, the Unites States of America had a Hawaiian fever.

Or so it thought. And many a traveler set off to the Hawaiian islands.

When he arrived, he expected to find a Polynesian wonderland of tiki gods, thatched huts, and topless wahines. Instead, he found that the missionaries who preceded him had erected Victorian homes, destroyed the huts and tikis, and covered up all the women. — from Smuggler’s Cove, by Martin Cate.

But rather than remain disappointed, travelers spread the Beachcomber’s Tiki craze to Hawaii. And so Donn Beach left for Hawaii. And soon after, so did Trader Vic. For one reason, and one reason alone, because “tourists expected tiki to be in Hawaii when they arrived.” (Smuggler’s Cove, again.).

Let me rephrase that. Hawaii, a native land with its own island culture, with its own customs and mores, was forced to accept “one man’s vision of an island rum shack, from an island located somewhere between his left and right ears”, to the point of importing Donn Beach himself, all because one man in California crafted a setting so compelling that people expected to see it in Hawaii.

That is the power of setting.

That is the power of setting.

The power to shape expectations about the past, the present, and the future to the point where people strive to make the imagined real.

Of one man’s fancy, so beloved by many, imposed onto reality itself.

And that is why we will embark on a survey of science fiction’s greatest settings. To see where we have been–and where we will be again.

This is awesome!

A setting so compelling that it forced itself into reality is meme-magic before that word existed.

Which makes for an interesting thought experiment. I’ve always been pretty sympathetic to the notion in Plato’s Republic that the kind of entertainment people consume tends to shape them, their minds and imaginations to such a degree that it is vital to the continuance of civilization.

The mystical vitality of the tiki bar as a setting indicates at least that the popular imagination can force its collective will into existence.