Brilliant sleuthing and twist endings have been kicking around SFF pretty much for as long as there has been a recognisable market for the genre – in fact, you could make a strong case for what we know as SFF to have emerged from the same kind of detective fiction that gave us Sherlock Holmes, and there is certainly a strong relationship between the SFF of the pulp era and the PI puzzlers that lived fast and hard alongside them.

Brilliant sleuthing and twist endings have been kicking around SFF pretty much for as long as there has been a recognisable market for the genre – in fact, you could make a strong case for what we know as SFF to have emerged from the same kind of detective fiction that gave us Sherlock Holmes, and there is certainly a strong relationship between the SFF of the pulp era and the PI puzzlers that lived fast and hard alongside them.

The category has definitely seen greats over the years, from near-superheroes like The Shadow and The Spider, through the science-with-a-twist everyman puzzle mysteries of the 40s, Robert Heinlein’s buzz-cutted, glasses wearing square-jawed geniuses, and Niven’s engineering puzzle boxes, and right up to the present with offerings like Butcher’s Dresden Files. Most of the greats put in their time spitting out mystery theatre of the mundane variety – Brackett’s offering in this area are well known of course, as are Moore and Bradbury’s collaborations on a series of psychoanalyst detective tales, and where would we be without Hamilton and Piper?

While Jack Vance is perhaps best known for “heroes” like Cugel the Clever and Rhialto the Marvellous, and for his more common knowledge work like Lyonesse and perhaps The Demon Princes,[1] his oeuvre is as broad as it is deep and many of his tales contain mysteries and puzzles, and occasionally even an actual detective.

So let me introduce a less-known member of Vance’s cast: Magnus Ridolph.

Magnus Ridolph makes his first appearance in the July 1948 issue of Startling Stories[2] – the magazine where Vance had made his debut just 3 years previously, and that’s where he stays until the last two of the ten stories Vance ultimately wrote, which ended up in Thrilling Wonder Stories (The Kokold Warriors in Oct 1952) and Super Science Fiction (Worlds of Origin[3] in Feb 1958).

These are fascinating stories that give us a great peek into the universe Vance was building in his mind, and that would ultimately become his Gaean Reach – which in various incarnations would serve as the backdrop for much of his science fiction right up to the end of his career.

Magnus is definitely not the typical detective hero one saw in the pulps of the time – indeed, in many ways he strikes the reader as being almost the diametric opposite: slight, frail, elderly, the snowy-goateed Magnus Ridolph is the kind of independently wealthy “tramp” that you might expect to see in the pages of a satirical novel of the Victorian era. Something like you might get if you created an unholy amalgam of Jerome K. Jerome and Kipling, perhaps. Just as Cugel is in many ways a parody of the usual sword and sorcery heroic lead, Magnus seems a poke in the eye of the Shadows and Sherlocks and other grim and earnest detective-adventurers of the day.

Each of the 10 stories begins on another world of Vance’s imagined future, and each begins with a problem – most often one revolving around one or another of Ridolph’s various financial misadventures, but in a few cases because his reputation as a trouble-shooter precedes him and the desperate locals have begged him to help.

In every case, though, the problem initially appears intractable – Vance carefully builds up both world and situation so vividly and completely that it seems that this time will surely be the time Ridolph fails. But we know he will succeed, so – like with Niven’s engineering puzzle boxes – we are drawn in to the world as we try to guess how the inimitable Magnus Ridolph will do it this time.

To be honest, some of these stories succeed better than others. There are a couple – such as The Howling Bounders (Startling Stories, March 1949) and The Unspeakable McInch (Startling Stories, November 1948) – where the twist at the end really isn’t well telegraphed and in fact relies on a knowledge of Vance’s universe that he hasn’t shared with us.[4] But for the most part Vance is deft in setting things up, so that you can’t help but chuckle when Ridolph comes up on top at the end with some brilliant solution that not only solves the problem but also leaves him richer…and also often humiliates the foil Vance has set up opposite our hero.

Magnus Ridolph really is an interesting character. In some ways Navarth from The Palace of Love seems to be an alternate version of Magnus, one where he fell into dissolution and post-modernism. In others, Ridolph seems much like the brilliant grandfather of Niven’s engineer heroes in Known Space in his ability to quickly think up intricate plans. Of course, the character he is most similar to may be Vance’s later character, the “galactic effectuator” Miro Hetzel[5] – though really Miro might better be seen as an early version of Vance’s various versions of Kirth Gerson.

As for the worlds themselves – they’re painted in bright acrylic primaries with Vance’s habitual brush, populated with the kind of vivid pseudo-Victorian characters and bizarre aliens[6] he seems to do so well. The language here isn’t as rich as in his later work, but you can see it coming in the way he layers description and draws out whole worlds in just a few lines. You might call these stories a kind of gateway drug to the more ponderous prose he offers in Tales of the Dying Earth and the Lyonesse cycle.

Sadly, although the Magnus Ridolph stories have been published in collected form time and time again over the years[7] these tales are little discussed, and little known – often even inveterate Vance fans have never heard of them. Equally sadly, many of the magazines in which these stories originally appeared aren’t yet available in digital form.

But they’re well worth the effort of tracking down originals or forking out for one of the anthologies – they’re short, clever, quaint, and quintessentially Vance.

[1] Which of course is itself a series of detective stories, after a fashion – and foreshadow his later work in the Cadwal Chronicles so well that you can instantly see Glawen Clattuc as a re-imagining of Kirth Gerson. But more on that in a later post.

[2] From the lurid covers, Startling Stories had a bit of a reputation, but after Sam Merwin took over as editor in 1945 he started pulling the mag up-market and by the end of the 40s he was competing directly with Astounding – no mean feat at the time!

[3] Later republished as Coup de Grace

[4] The King of Thieves (Startling Stories, November 1949) is a borderline case – he hints at the solution early on, reminds us of it again to let us know that it’s important, but doesn’t really tell us anything about it. For “puzzle box” stories, I think this is cheating – the fun of such things is to be able to go back through the story and see where you really should have seen it coming.

[5] See Vance’s The Dogtown Tourist Agency(Epoch, 1975) and Freitzke’s Turn(Triax, 1977) – both anthologies edited by Robert Silverberg

[6] And the aliens are almost always a key to the problem.

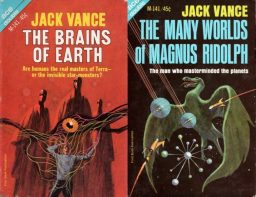

[7] First in an Ace double with Vance’s The Brains of Earth in 1966 – thank you Donald Wollheim! – and over and again until the last edition was assembled with all 10 stories in 1984. This version was reprinted as part of the Vance omnibus.

Jack enjoyed writing straight-up detective/crime fiction as well. He even won an Edgar for “Best First Novel”. Two good links:

https://www.amazon.com/Dangerous-Ways-Jack-Vance/dp/1596063599

http://www.dosomedamage.com/2013/06/jack-vances-contributions-to-mystery.html

-

“[Vance] regarded things like universal language and FTL in his own stories as conventions that were simply the necessary backdrop to permit the type of stories he wrote.”

And THAT is just one reason why Jack should be considered a pulp writer. Vance was all about telling an entertaining story. It’s no surprise that he was a fan of ERB and Robert E. Howard.

“Brilliant sleuthing and twist endings have been kicking around SFF pretty much for as long as there has been a recognisable market for the genre – in fact, you could make a strong case for what we know as SFF to have emerged from the same kind of detective fiction that gave us Sherlock Holmes…”

Poe and Doyle both wrote damn good SF. In fact, there are plenty of hints that ACD would’ve preferred to keep on writing tales of Professor Challenger and let Sherlock stay dead at Reichenbach Falls.

“First in an Ace double with Vance’s The Brains of Earth in 1966 – thank you Donald Wollheim!”

Haven’t you heard? I have it on good authority that Wollheim was the KGB’s Manchurian Candidate in the SFF community during the ’60s and ’70s. DAW Books, with all of that swashbuckling space opera and sword & sorcery, was a Brezhnev-approved operation. Fiendishly insidious! Little did stalwart conservatives like Gordy Dickson, John Norman, Jerry Pournelle and Poul Anderson know that they were all pawns of the Kremlin!

By Jove! How could I have missed the connection – why: both organizations are named with three letter acronyms! It’s so obvious!

Seriously though, Wollheim, as an original Futurian, was a bit of a thorn in the side of the New Wave. It’s easy to see how they grew (in a sense) out of the neoFuturian group that congealed around Knight, but somewhere the NW writers rejected the utopian vision of human destiny and that seems to have rubbed Wollheim the wrong way. He famously (well, in my circles…) tagged Campbell as nationalistic and technology focused rather than a utopian idealist in his book The Universe Makers (1971) – basically identifying himself with a branch of SF originating in Wells and Campbell in the branch originating in Verne.

Which is to say – I really don’t think he cared about the politics of the writers, only their philosophy of the future. Did they believe in the human spirit and “a destiny in forever” as it were, or were they more damn nihilists? That was the question he asked, and people like Anderson and Vance and even Harlan Ellison (who may have been writing downer fiction but always seemed to inject a sense of “never give up”) seem to have passed his test.

Just another reason to Be Wollheim.

-

Right on. Wollheim chided Brian Stableford for being too “downbeat” in this passage:

Wollheim was the biggest booster — in paperbacks/digests — of Merritt and Robert E. Howard in the ’50s. He created the Burroughs Boom in the ’60s. The KGB is truly insidious.

Fascinating post, Kevyn. I haven’t read a Ridolph story in so long I had forgotten he was one of Vance’s characters!

Thanks for the reminder.

Great article. Certainly one of Vance’s most underrated and overlooked characters.

I have a copy of The Many Worlds of Magnus Ridolph collection sitting on the shelf waiting to be read. Maybe I will make it my next Vance after this post!

Can also be found collected in “Magnus Ridolph” at https://jackvance.com/ebooks/shop/?q22_action=view&q22_id=60