The elements of fantasy and science fiction are everywhere, but the core of what really made the old stories function has evaporated. For instance, Rogue One is routinely compared to The Magnificent Seven, but only the most superficial aspects of the classic Western’s premise are carried forward. The overall approach to how characters are established as being either likable or unlikable are worlds apart.

The elements of fantasy and science fiction are everywhere, but the core of what really made the old stories function has evaporated. For instance, Rogue One is routinely compared to The Magnificent Seven, but only the most superficial aspects of the classic Western’s premise are carried forward. The overall approach to how characters are established as being either likable or unlikable are worlds apart.

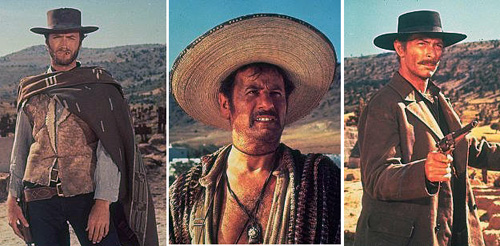

What do I even mean when I talk about likable and unlikable characters…? That’s a fair question. And to delve into it, I’ll use the classic spaghetti western The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly as a reference point.

Notice how in the film introduces three outlaws, and then establishes and develops their likeability or unlikability with every scene. Yes, the plot has to move along to its epic conclusion. But in some sense, the plot is just a device for showing the character qualities of its participants.

- There’s “the man with no name”, the Good. He pulls off these insane scams of turning in outlaws for a reward and then shooting them off the gallows and riding off to the next town to do it again. It’s hilarious. It’s also sketchy. To maintain his likability as a protagonist, he is shown to only shoot the hats off the townspeople when he does this.

- There’s the bandit character, the Ugly. He’s a scruffy underdog brought in for comic relief. He’s not the most reliable ally you could choose for an adventure. But note that it is left unsaid whether he actually committed all the dastardly crimes that he is accused of. He treats “the man with no name” so harshly, his likability is at stake. To recover it we are shown the rare bit of back story to make him more sympathetic: he was so poor he had to choose between being a priest or an outlaw. And if the audience can’t respect his being an outlaw, they can at least acknowledge that he chose the more “manly” path.

- Finally… there is the Bad. This guy is simply a cold-blooded killer. However to him… it is only a job. And he treats it like one; you’ve got to respect that! But given that he is the heavy here and that you really want to the audience to cheer when he is finally defeated, there is some work here to do on the part of the writers. How to establish his unlikability…? Give him a position running a concentration camp. Is that enough? Nope. They have to show him forcing the southerners to play music in order to cover up the fact that he routinely beats them senseless. Is that enough…? No it isn’t. To really clinch the deal, he is shown to be looked down on by a Yankee officer that has failed to uncover solid evidence of his wrongdoing.

Now compare this to Scarlet O’Hara’s character in Gone With the Wind:

- She is shown to marry a goof for no other reason than to hurt the guy she is actually in love with.

- She relegates her sister to a life as an old maid by stealing her beau… whom she only wanted for his sawmill.

- Though she treats her husbands coldly, they are nevertheless shown to be willing to sacrifice themselves for her honor at the drop of a hat. That done… they are nothing to her.

- She has one friend that is willing to stick up for her socially, stand by her through thick and thin. And it is that one friend whom she is willing to betray by throwing herself at her husband.

If Gone With the Wind is any indication, then traditional virtues are irrelevant when presenting a heroine to largely female audience. Heroes? Even of the larger than life outlaw variety…? Those guys are absolutely going to be judged on whether or not and even how much they can be respected on a scene by scene basis.

And of course, the Scarlet O’Hara effect is in operation consistently with heroines to this day, even with characters like Katniss or Bella Swan who are not shown to be even half as rotten. Characters like Rey and Jyn Erso necessarily suffer from this as well. These characters are cast in a traditionally heroic role… but they are not required to follow the same rules as the people that preceded them.

Hmmm, if I may go off on a tangent here I hadn’t really thought of ‘Rogue One’ as a ‘The Seven Samurai/The Magnificent Seven’ type movie until you brought it up. Funny that ‘Battle Beyond the Stars’ was a SW take-off that intentionally modeled itself after the ‘The Seven Samurai/The Magnificent Seven’ that was far and away better than ‘Rogue One’. Sure it’s as goofy as hell but it’s full of fun, which Disney seemed to have extracted as much as possible from their SW films.

It makes sense that there would be different rules for what makes a female character likeable or not, but the question is, what are they? This post establishes that whatever they are, they are not honor-based. I look forward to any future posts exploring what they might be.

I myself hated Scarlett O’Hara, but there are obviously many who don’t.

I think you’re cherry picking a bit here, but there ARE plenty of romantic comedies where the chick trades up. You couldn’t cast a male doing the same, most men would despise him.

-

When adjusted for inflation, Gone With The Wind is the most profitable movie of all time. How is that cherry picking?

Great post, Jeffro. I’m looking forward to the comments and any follow-up you choose to do.

Wandering off into the Scarlett O’Hara briar patch, I remember reading that Margaret Mitchell never considered Scarlett the heroine of the book; she simply took over the story, as characters will do. The real heroine was Melanie. If we go by that, we have a heroine who is loyal (knowing full well how her friend feels about her husband); willing to stand up to the slings and stones of an often cruel society in defense of a woman who doesn’t really deserve it (Christianity in action/chivalry?); clear-sighted enough to see the Southern way of life she loves is gone, but supporting her husband and ideals just the same; and having courage and fortitude – enough that she drags herself from the bed where she’s had a difficult labor to deal with Yankees. All characteristics that make a pretty good heroine. Or hero, for that matter.

I should probably actually go see Gone with the wind.

The movie in my head accumulated through clips and the cultural zeitgeist is of Scarlet being a complete heel and in the end she is destitute and so begs the lead man to save her and he says to her “Frankly dear I could give a damn” and then leaves her in her destitution.

Roll credits.

Anyway if one person’s impression of a movie he has not seen is any indication Scarlet is judged as a bad seed who gets her come-up-ens.

-

My idea too, having never seen it. I never really figured we we were supposed to think Scarlett was a good person. But then I didn’t see it.

-

My idea too, having never seen it. I never really figured that we were supposed to think Scarlett was a good person. But then I didn’t see it.

-

I have seen it (once, a long time ago), and I think this is correct. Scarlett’s pride is sort of a virtue and a curse at the same time, as I recall. She has a fierce never say die attitude but she’s also kind of self-destructive. She really needs a good man (i.e., Rhett) to straighten her out but her pride won’t allow her to accept it. Maybe my memory is off but that’s how I remember it.

I gather that a lot of women love the idea of Scarlett’s life in that she’s rich, lives on a beautiful plantation, and wears pretty clothes, but they relate to her flaws, not because they think she’s a role model.

-

-

Based primarily on the book (the movie too as I recall), Scarlett is not left destitute. Rhett will return from time to time “to keep up appearances”. The Rhett Butler line of “I don’t give a damn” is in response to Scarlett’s profession of love for Rhett. He just can’t take the disappointment anymore.

-

The preceding line is “Whatever will I do? Wherever shall I go?”, so it seems related to Scarlett’s state at least to an extent. Though I don’t recall her being destitute.

-

I think that the appeal of “Gone With The Wind” was not that Scarlett gave girls someone to pretend to be but that Scarlett gave girls someone to pretend to be better than.

It’s less “if I were Scarlett I would have…” and more “if I were there I would have shown Scarlett a thing or two…”

I’m not sure if this is part of a general tendency regarding the different ways that males and females insert themselves into a story, but it might be. There’s a reason that “Mary Sue” is used as shorthand for a character inserted into an existing franchise.

I’ll just point out that Lady Carla in Willocks’ “Tannhauser” novels is probably the best literary heroine created in the 21st century. Very strong but utterly feminine. She overcomes obstacles solely through feminine wiles/intelligence and by strength of will. Her bf/husband is pretty damned cool as well.

https://www.blackgate.com/2016/09/13/the-religion-by-tim-willocks/

There was something (I want to say here) recently where someone was discussing “masculine” and “feminine” romances. The difference being in how the protagonist chooses, when forced to, between love and honor.

The masculine romance was typified in CASABLANCA, the writer said. Honor or Right gets the nod. He may or may not be given a chance to have it both ways in the epilogue.

In the feminine version, not so much.

Women seem able to enjoy both types. Men, not so much. Or so the comment seemed to say.