Movie Quotient and How Ghostbusters (3) Missed Its Market

Thursday , 21, July 2016 Uncategorized 4 Comments

Rebusion: noun – mass confusion resulting from the reboot of a familiar franchise using unfamiliar or uncharacteristic elements. See also: Jar Jar Binks.

The third Ghostbusters movie is out (confusingly named Ghostbusters – In what I believe is a cinematic first: a science fiction series reboot with the identical name as its original cinematic inspiration.) Despite a massive marketing budget, a passionate built-in franchise fanbase, and a massive amount of additional free media publicity due to crafty hot-button pushing by Sony Pictures, it underperformed in its opening weekend and is looking at daunting, perhaps impossible, box office targets to break even.

Budget (incl. marketing): 144 million USD

Projected Box Office: 130 million USD (Actual: $46 million in opening week)

This oversimplifies things, of course, as these figures ignore both marketing costs (likely another $150 million) and overseas box office revenue. But the upshot is: the movie stumbled out of the blocks on what was a low-competition weekend. It missed its target market pretty badly.

It might come down to its Movie Quotient. Since movies are neither as in-depth, mentally challenging, or as complex as the average novel, I think it is fairly easy to develop a formula for what makes a successful mass market movie.

By taking a look at five factors: a movie’s economics, internal rules, character distinctions, plot arc, and production values, you can begin to anticipate how well a science fiction movie will appeal to its target audience.

Economics

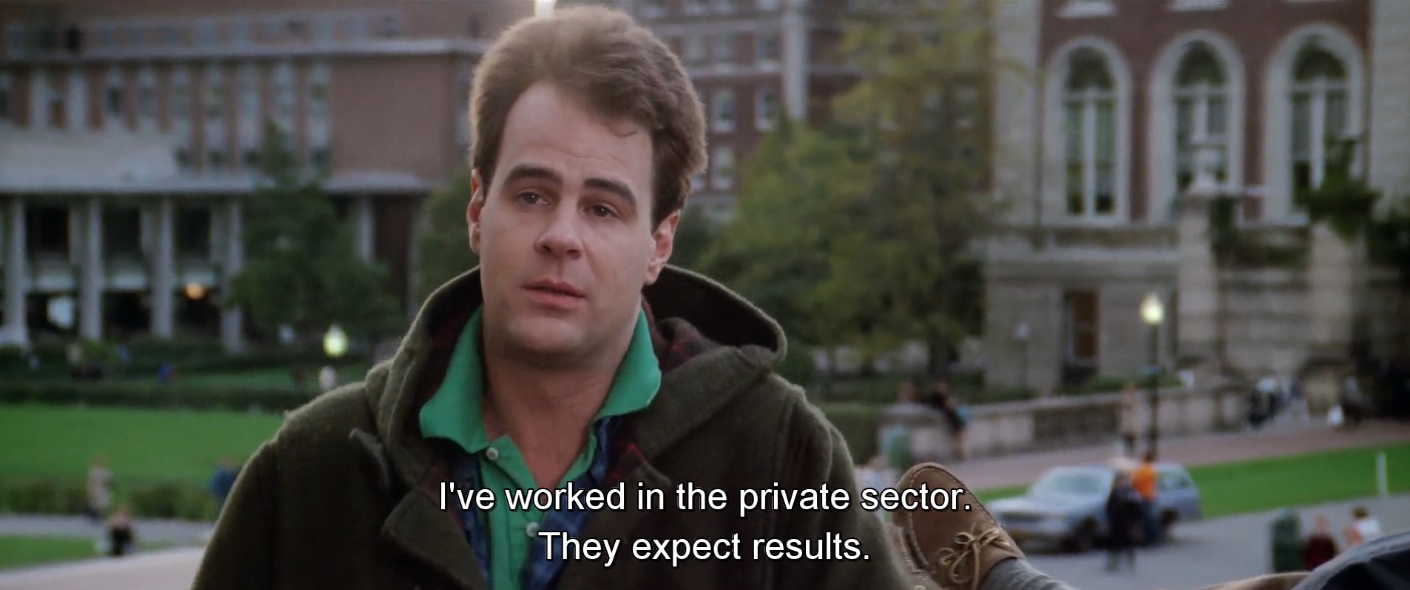

All movies, but science fiction movies in particular, need to have an internal economy that makes sense. Reasonable economics can help ground a movie that acts you to suspend disbelief in other areas, and also provides ready-made conflict. In the original Ghostbusters, the economics were simple but realistic. The three founders were fired and in desperate need for employment. The most entrepreneurial of the three (Peter) convinced the team to go into business as service start-up, using a triple mortgage at 19% interest…on Ray’s parents house. Even with that, they are barely able to afford an abandoned firehouse in a horrible neighborhood. Their fourth member is just a regular joe in need of a job, any job. Their secretary is highly competent, if a bit exasperated at the ridiculous nature of the business venture. The sluggish economy is a significant, if simple, hidden conflict that drives much of the movie, and provides a common situation that the audience can relate to. This plays out throughout the movie, as the venture also faces drastic consequences against the wrath of regulators like the EPA and other political enemies.

In Ghostbusters 3 (the new one – so designated to avoid confusion), the economy is irrelevant to the plot to the point that the audience has to do mental gymnastics just to accept that there is anything driving the main characters at all. In this version, the main founder (Erin) loses her job at Columbia for believing in ghosts, but never appears distraught about the loss of income. The other two founders likewise lose their jobs at a discount college, but immediately begin shopping for a location for their new ghostbusting business. Their secretary applies for the position because he is functionally retarded, and is hired because no one else bothered to apply. Their fourth member joins without an interview, because she thinks it is a club that sounds fun, and actually quits her job to devote herself full-time to club membership. Their only political opposition comes from Homeland Security, which wants them to agree to appear to be outlaws publicly, while continuing their important ghostbusting investigations in secret. Also, despite having an apparent unlimited budget for high-end nuclear technological innovation, they can’t afford a station wagon, and instead enlist their volunteer club member to donate her uncle’s hearse.

This lack of internal economy hurts the movie with regards to the target audience. If regular people can’t relate to a believable, grounding set of economic motives, it lets a lot of the air out of the balloon at the outset.

Rules

Science fiction always has internal rules, whether it is a book or movie. The audience hates when an agreed upon rule is broken. See also Midichlorians. Most movies, being swift affairs, need to establish those rules (either subtly or overtly) early in the film. The movies that do this tend to improve their MQ.

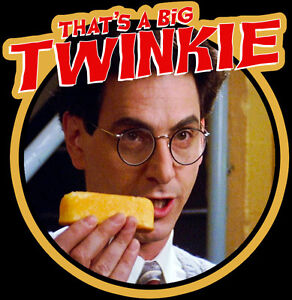

In the original Ghostbusters, a lot of rules are established in the brief opening scene: ghosts are real, malicious, and terrifying (without necessarily being violent.) The library ghost does not appear on screen in that opener, and its only effects are floating books (unseen by anyone) and a light and wind that overwhelms the poor librarian. Then, within the first ten minutes, the banter between the main characters establish quite a few more rules: science can apprehend the concept of a ghost, and there are physical measures that can be used to categorize different classes. Even armed with this knowledge, the ghosts are still scary and difficult to pin down. Later in the movie, other rules are established: something is accelerating ghostly activity, don’t cross the streams, etc.

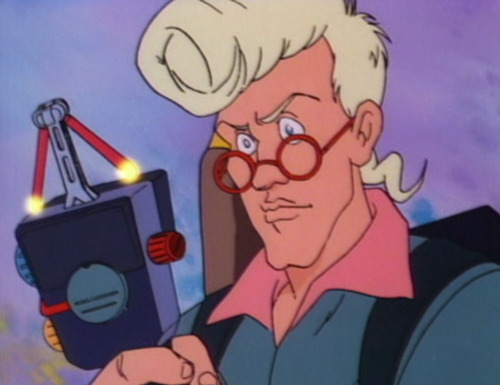

In Ghostbusters 3, what is established is that the most spectacular ghost of the movie will appear in the opening scene. Instead of floating books, it destroys the floor, explodes a staircase, attempts to murder a museum docent…and is somehow generated or enhanced by something that looks like scientific ghostbuster equipment. In fact, the movie will later acknowledge that the villain is using the same equipment that the ghostbusters use to trap ghosts, only that he is using it make ghosts appear, or be more powerful or something. It was really hard to tell. It also turns out that the villain learned how to make this equipment by reading a book by the leader of the ghostbusters (Erin), even though the team’s lone equipment designer is a different character (the blonde one who looks like Egon from the cartoon).

Confusing or non-existent rules are something that can make some people in the audience feel cheated.

The Story Arc

There are plenty of variations on the basic story arc, but if you are looking to maximize your entire core audience’s enjoyment (and there are plenty of reasons NOT to do this, as long as you are messing with it intentionally, and understand that you are going to lose some people), it is best to deliver the traditional plot where things go from bad to worse to worst before resolving in some spectacular and climactic way.

The basic story arc. It is easy to invert this graph (think the spectacle at the beginning of Revenge of the Sith – it immediately raised the plot’s bar to climax levels, leaving the rest of the movie to unwind aimlessly and without purpose.)

The original Ghostbusters starts small and subtle, and builds its spooks in an effective way: the ghosts start invisible, then nice looking, then violent-looking (but otherwise without physical substance), to physical (slimer), to demonic activity of the refrigerator, and so on. Likewise, the general plot moves from job-loss, to making budget, to mastering the tech, to losing electrical power to bureaucrats, etc. The plot is simple but builds.

Ghostbusters 3 starts big, but upon the first confrontation with a ghost, the new team is deliriously happy and unfrightened in any way. In fact, the only one of the ghostbusters who is ever sensibly afraid of the ghost is the fourth member, who joins the “club,” apparently as a volunteer. There are other random spikes in the plot which cause the “climax” to be a drawn-out, incongruous affair where the giant enemy is revealed to be…the Ghostbusters logo (which was randomly designed by a graffiti artist conveniently when the team was struggling to design a logo…)

In Ghostbusters 3, the team’s biggest concern is their own logo.

The worst of these spikes is when, in an uncharacteristic fit of rage against a random skeptic, the team leader (Erin) maliciously releases the team’s only captive ghost, who then murders the skeptic. This comes in the middle of the movie, and has no consequences or aftereffects on the plot.

Disregard the story’s arc, and you disregard your audience.

Character Distinction

The original Ghostbusters had simple but effective character distinction: you had the shrewd opportunist, the true believer, the uberrational scientist, the everyman, the beleaguered smart aleck, the nerd, the realist, etc. Sure, Sigourney Weaver went from reserved and sensible to assertive and sexual once possessed by Gozer’s familiar, and Rick Moranis went from nerdy and flinchy to rabid dog, but the dynamic between the two characters was still within character. When Egon was terrified, he didn’t get emotional, he simply logically explained why he’d lost all capacity for rational thought. When true believer Ray kept his mind “clear,” he kept it clear by conjuring a childhood memory. Peter never stopped thinking about his angle with women or fortune. These traits held together.

In contrast, Ghostbusters 3 had two main characters who, once they resolved their long-standing differences within the first five minutes of reuniting, were interchangeable. The team of three dumpy scientists and a lifelong desk jockey and history buff, despite demonstrating absolutely no athletic training or ability throughout the movie, are endowed, at the darkest hour, with supernatural ninja skills without any explanation. In a five minute battle scene, the four dispatch a horde of ghosts without a scratch. Worse, even the most consistent character, the retarded secretary, randomly decides he wants to be a ghostbuster, appears on nuclear motorcycle and is subsequently possessed by a ghost, at which point the motorcycle and his desire to be a ghostbuster are irrelevant to the plot. The one distinct character is the cartoon Egon lady, who mugs and adlibs incessantly. So, it isn’t really a good distinction.

Production Values

Obviously, if it is science fiction, it needs to have a style that suits the movie. Ghostbusters, despite being 30 years old and suffering from the old animation restrictions of analog special effects, has somewhat better production style than Ghostbusters 3. It just seems like the audience should get better visuals out of a movie that cost this much to make, and should be set in a New York that seems like New York, instead of Massachusetts. Having said that, production style was definitely the new movie’s relative strength.

When determining a film’s MQ, I kept thing simple. I measured each of the above categories on a simple 30-point scale: 0 if the category wasn’t attempted at all, 10 if an attempt was made that failed, 20 if the movie did it simply, and 30 if the movie did it in a complex or inventive way.

Interestingly, it appears that out of the movies I picked, the ones that tend to have success with the widest audiences are the ones that fall between 100 and 120 MQ. The ones that are lower have at least one off-putting flaw for the masses, and the two movies that scored 130 are definitely more limited in appeal than the ones resting in the sweet spot.

Ghostbusters 3 lands in the same MQ territory as Flash Gordon, Maximum Overdrive and Battlefield Earth. Probably not what the execs were looking for when they plunked down $300M+ for a tentpole revival.

| Economics | Plot Arc | Rules | Character Distinction | Production | Movie Quotient | |

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | 30 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 130 |

| Interstellar | 20 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 130 |

| Alien | 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 120 |

| The Martian | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 120 |

| Star Wars: A New Hope (NOT Special Edition) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 120 |

| The Shining | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 120 |

| Matrix | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 110 |

| The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Sutherland) | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 110 |

| Pirates of the Carribean | 10 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 110 |

| Road Warrior | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 110 |

| Ghostbusters | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 |

| Guardians of the Galaxy | 10 | 20 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 100 |

| John Carter of Mars | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 100 |

| Quatermass and the Pit | 30 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 90 |

| Revenge of the Sith | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 90 |

| The Day the Earth Stood Still | 20 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 90 |

| Gravity | 10 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 80 |

| Zardoz | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 80 |

| Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 80 |

| Mad Max | 10 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 70 |

| Flash Gordon | 0 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 60 |

| Ghostbusters 3 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 50 |

| Maximum Overdrive | 10 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 50 |

| Battlefield Earth | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 50 |

| Plan 9 From Outer Space | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 30 |

True. Also true: Flash Gordon and Maximum Overdrive are watchable fun. Great movies? No, but great fun, yes. This new GB? Doesn’t look fun.

I won’t go so far as to say it was unwatchable. After all, the bit with King playing a rube at the monster ATM machine in MO is as cringeworthy as crazy blonde riffing on Pringles in GB3, but there was sort of a marvel at watching a major motion picture absolutely whiff on the gimmes. Not to get too political, but it was Cruzesque. A movie this expensive hasn’t blown it this badly with its own core market since the Speed Racer. It could sink Sony Pictures.

Having said that, it misses beats so consistently that it almost seems as if the movie was dismantled on purpose.

There is a prevalent attitude in film production companies (and, sadly, often in book publishers as well) that SF/F doesn’t need to be logically consistent.

I’ve seen it expressed by reviewers, too, who sneer, “You can’t expect a movie about about giant monsters and robots to be realistic.”

Yes, actually, we can, and we do. Having fantastic elements makes realism in the rest of work more important, not less.

The first Ghostbusters worked largely because of the solid, almost cynical, realism of the characters and setting. Peter Venkman was such an obvious fraud that anything that he accepted as real had to be an undeniable fact.

The Ghostbusters’ economic struggles, the over-the-top media attention, Dana Barrett’s attempts to rationalize her experiences all left the audience feeling that, if ghosts were real, this is exactly how ordinary people would react.