I have been thinking a lot about the pulps lately, in particular about what made some of the early pulp SF greats so enduring, and what went into making the most enduring magazines endure.

have been thinking a lot about the pulps lately, in particular about what made some of the early pulp SF greats so enduring, and what went into making the most enduring magazines endure.

In search of answers, I was perusing the Center for Fiction website today when I came across this article by Victor LaValle.

In a nutshell, this is the tale of two skilled and educated writers[1] who have suddenly come face to face with the fact that narrative had never been a big part of their training.

In LaValle’s words:

There’s a kind of blind spot, an essential flaw, in the workshop method that contributed to our problem. In class we’d discussed each submission seriously, were schooled about our characterizations, our use of language, our voices, our ideas. But we rarely, if ever, discussed the structures of our stories. Never examined the reasons why we’d told this story in this order.

This epiphany comes to them when LaValle’s friend calls in a daze, realizing that the comic book panels he has been scripting in his new job are just sudden cut scenes from conversation to conversation. What could it all mean? Did their prose stories boil down to much the same?

What they realized, suddenly, was that the demands of writing for comic books were exposing a gap in their training: it wasn’t necessarily that they couldn’t write a coherent narrative, but that the focus of everything they’d done so far had been elsewhere, and they were suddenly realizing: they didn’t know how to think about the narrative.

A tightly written story is a beautiful thing. Even when the characters are cut-outs, the dialogue wooden, and the clichés are thick on the ground – if the beats come just right then odds are good that’s a story you will have trouble putting down.

Reading this little blurb about the way in which comic book writing had thrown their lack of narrative training into relief reminded me of my question: what was it about the best of the early pulp writers that made them work so well?

These modern writers were learning how to analyze their narratives, how to think about the attack and decay of beats, the sequence, how to build a climax and how to pull together disparate threads to make a point, all this by looking at their writing through the lens of comics.

What about the SFF pulp greats?

I think it was detective stories.

Looking back, it seems so obvious. If you take a look at some of the best known names from the 30s and 40s, which is arguably the peak of pulp SF, the best were known as much for their mysteries and their detective fiction as for SF or fantasy.

Look at C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner – between the two of them they turned out any number of mysteries and hard-boiled detective stories.

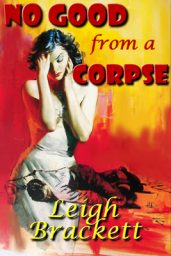

Look at Leigh Brackett – as well known in some circles for her hard-boiled novel No Good From a Corpse and her screenplay for The Big Sleep as for any of her space opera in SFandom.

Look at Dorothy Sayer, look at Dennis Wheatley.

All of these writers worked with mystery and detective stories just as much as Arthur Conan Doyle did with his Sherlock Holmes tales and later Agatha Christie with her murder mysteries. And the one thing that ties this all together is that for a mystery of any kind to work effectively for the reader the author must master two things:

- The timing of the story beats

- The weaving together of divergent narratives into a whole

The proof?

Further forward, let’s look at Ray Bradbury, Moore and Brackett’s young padawan – his stories may never have drifted into detective territory, per se[2], but they have that same fine grasp of timing and control. He takes that mastery of tight storytelling he learned in Moore’s living-room and applies it masterfully to build a sense of other-worldly disconnect in his Martian Chronicles stories, to misdirect and surprise in tales such as The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, to build tension in stories like Chrysalis.

Look at H. Beam Piper[3], whose detective slate novel Murder in the Gun Room is perhaps his best work, but whose skillful handling of timing and complex threads shows itself in his story He Walked Around the Horses and others of his Paratime Police series.

Look at Andre Norton, who again draws on the legacy of the pulp era greats and like them in her early work she wrote crime fiction as well as SF – and you can see that way of thinking in the structure of her Time Traders stories.

These writers were writing across genres at a time before the development of our modern silos, and the majority of the early masters wrote at a time before genre publishing was any way to make a living. Those who truly wanted to earn their bread with their type-writers couldn’t possibly rely on science fiction alone – even if their output was sufficient to buy food at a penny a word (or less!) there simply weren’t that many dedicated venues.

No, to pay the bills they needed to think in terms of the full range of possibilities, and they wrote not only science fiction but also crime, detective/mystery, western, fantasy, adventure, and weird fiction.

The majority of pulp era authors faded quickly of course – they burned out, perhaps, or were simply never really good enough to last.

But the best?

The best pushed on and were well known well into the 60s and 70s, before The Great Delisting – and the market is really just starting to rediscover them again now (though of course they were never completely forgotten, just so difficult to find that only grey-haired or truly dedicated young fans would be likely to come across them).

The best of their protégés obviously learned these same rules, and added to it the next generation’s ideas to enhance characterization and colour.

I think it’s no mystery why so many of the best writers of the pulp era and the generation after wrote for radio, film, and TV as well as for print – many of the “beat” rules they learned transfer very well to the demands of visual storytelling. And this, of course, is why attempting to write for comics threw the lack of focus on these rules in modern writer training into such sharp relief.

In modern writer training, the kind of close one-on-one mentoring that previous generations enjoyed is less common. On top of that, many of the tools that those pulp masters forged and passed on to the next generation have come to be seen as “obvious” – so workshops and similar training venues tend to focus on other things: the artistry of character and colour, the feats of world-building that we’ve come to expect.

Basically, what’s happened is that literary fiction has gained the luxury of being somewhat lazy: it’s become possible to obsess about painting scenes and generating atmosphere without much consideration for the other dimensions of a good story. Make no mistake, there are great authors today – maybe better authors in some respects than in decades past (though I submit that the best of the pulp era would fare as well today as they did then). But there’s hardly anyone teaching this generation of writers how to keep a beat.

Partly, I blame the siloing of genres – it’s possible now to make a living writing nothing but science fiction, perhaps nothing but a specific sub-type of science fiction. And the sheer volume of writing being published is astounding – even if they wanted to, many writers can barely keep up with what their peers are writing, let alone delve into other realms of publishing to see what the others are doing. And of course the pay is much better – oh, it’s still not a lot, and the majority of writers will still need to heed that advice: “don’t quit your day job” but it’s no longer necessary to add crime fiction and westerns, and radio plays and TV dramas and film scripts to your bibliography just to ensure enough income to justify the time spent writing.

[1] Though to be honest, I’ve noticed that “education” in writing means very little and often something bad. Like any craft, practice and experience count for so much more than training.

[2] Though he definitely injects mystery into a lot of his better work.

[3] Not strictly a pulp writer in terms of period, but the influence of the pulps is clear in his writing – and in fact may be one of the reasons he didn’t see as much success in his lifetime as he deserved.

Great stuff! Hopefully — if enough people keep saying it — everybody else will finally take a look at the detective pulp stories. I came to the genre late myself.

Bloch, Derleth and Vance also wrote mysteries/detective fiction. Vance was quite well-respected in that field. The prose of Moore and Brackett would NOT have sounded the same without the influence of the hardboiled guys like Hammett and Chandler. Robert E. Howard didn’t think a lot of detective stories, but he definitely DID “splash the field” and wrote for all kinds of pulps. Who knows? If he’d lived, he might have ended up — as pulp critic Don Herron thinks — out-Spillaning Spillane. He most definitely would have moved harder into the Western fiction market. He was already doing that.

As I’ve noted before, the Western and detective fiction genres have done a LOT better sticking to their pulp roots compared to the SFF field. Then again, they never really had Campbells, Ballantines and Futurians to derail them.

“Basically, what’s happened is that literary fiction has gained the luxury of being somewhat lazy: it’s become possible to obsess about painting scenes and generating atmosphere without much consideration for the other dimensions of a good story.”

Yep, much of modern fiction in the West has “First World problems”. The pulp guys, on the other hand, had to worry where their next meal was coming from.

-

That mystery/detective element was often present in Vance’s SF and fantasy stories, too. Demon Princes and Araminta Station, just on top of my mind. And it sometimes surfaced id REH too, regardless of how he might’ve felt about it.

-

Absolutely – you can also see the influence of other “genres” in his work: westerns, chinoiserie, frontier adventure. Also interesting is that Vance is quoted as saying:

“I don’t like being called a ‘science fiction writer.’ I am totally indifferent to all that stuff. I am outside all trends and fashions of any kind.”

But really, I’d be hard-pressed to identify any of his work that couldn’t be filed under SFF.

I’d guess that what this means is that he wasn’t trying to write SFF stories, he was trying to write *good* stories.

-

Jack’s contributions to the field of mystery fiction:

http://www.dosomedamage.com/2013/06/jack-vances-contributions-to-mystery.html

-

Deuce and Keyven,

Can I bring your attention to Conops, Dashiell Hammet’s first character? (Red harvest is the most well known story from that series) and the Thin man has an oblique reference to Conops (as in working for the agency)

I haven’t read the series yet but it intrigues me because I’m suspecting it’s a mix of grimdark hard boiled detective with thriller, intrigue, maybe romance and Old testament style justice genres all happily mixed up.

Keyvan’s critique might apply to English language writers but not to the Romance language ones.

For example Vargas Llosa has written fiction, historical novels, a dectective story with political overtone, a play, literary criticism.

Toni Soler is an historian who’s the head writer for the very popular political satire show Polonia (and before that Cracovia) he’s written a popularization of Catalan history, an althistory scifi novel; I think he’s done radio too.

Idelfono Falcones (writes in Spanish but is considered a Catalan writer) was a lawyer. He’s strictly historical fiction but he’s practically an archivist because the stories he’s done shows he’s read the primary sources and says so in his aftermaths

In Quebec, a lot of the French writers, are teachers, columnists, playwrights, screenwriters, novels, poets and so on.

Jordi Sierra i Fabra was a journalist who covered the Spanish speaking musical scene and he writes in every genre including youth lit (which called juvenil in both Catalan and Spanish)in both Spanish and Catalan

I suspect that it’s a similar phenomenon with the Baltics and the minority Slavic languages.

-

I wouldn’t say the Continental Op stories are grimdark, at least not in the modern sense, although they are about as hard-boiled as you can get. The Op is quite ruthless but Hammett’s protagonists tend to be highly principled. Sam Spade is no nice guy but as he says, “When a man’s partner is killed, he has to do something about it.”

-

There used to be a Complete Continental Op ebook. It’s since been broken down into smaller, over-priced sub-volumes. But my library still has the complete ebook. Try your library!

-

The two Continental Op novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, are my favorites of Hammett’s novels, though my perspective of the other three is probably colored by the movie versions.

Some people argue that Akira Kurasawa’s Yojimbo is based on Red Harvest (by extension A Fist Full of Dollars would be too). Interestingly enough Yojimbo does lift a scene out of the 1942 film adaptation of Hammett’s The Glass Key so Hammett’s influence is there for certain.

-

You are correct – the shift away from “genre blending” and applying techniques from various genres is very much an English language publishing phenomenon, and actually largely American. You can see the shift into siloing right through the 60s and 70s, and it accelerated during the 70s and 80s with the boom in large chain bookstores and the consolidation of both publishers and distributors.

-

Don Herron — whom I mentioned in my first post — is considered by many to be the foremost REH scholar/critic, though there are a few other names tossed out now n’ then. However, he is the unquestioned world authority on Dashiell Hammett. If ya wanna know about Hammett and the Continental Op, just check out Don’s site:

Andy

Quite right and thanks for bringing it up. I liked Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe precisely because they held to princoples and paid for it.

They never did take the easy way out.

Something the upcoming or prospective authours need to keep in mind.

xavier

I agree that the siloing of the genres is a problem, especially as each genre has started to look inward instead of outward for inspiration. Everything starts to sound the same.

Another interesting point is that that best storytellers would pick different structures based on the needs of their store. While Lester Dent’s formula might have been a sure-fire seller, the best showed mastery of far more types of structures, including some not commonly seen in today’s days of Hero’ Three Act Save the Cat…

-

+1

And a shout-out to Fredric Brown who was a fricking master at both genres. Mickey Spillane’s fave author, er, writer, amirite Mick?

Within a few sentences, you know you are in good hands.

“The Far Cry” and “The Deep End” are well worth anyone’s time. “The Fabulous Clipjoint” won an Edgar.

There was a series of his short mystery fiction published. Hard to find, but the LA Library had a few.

-

Oh, and Madball is the best carny mystery/thriller ever. Brown worked in carnivals for a time and featured them is several stories.

-

Fredric Brown is definitely one of the under-remembered greats – it’s stunning how often his stories made it to the radio in the 50s, which is a real testament to his broad appeal. I think a lot of that had to do with his ability to blend popular genre techniques.

Interestingly, it seems as though a lot of the writers who ended up forgotten during The Great Delisting were multi-genre – or maybe better termed genre agnostic. They borrowed and mixed, fitting the technique to the story they wanted to write, not the supposed genre. The result is that they aren’t clearly remembered as SFF authors today, and tend to get forgotten.

-

That could even be said of Poul Anderson, who — as Morgan noted a couple years ago — had an extremely wide breadth of stories while staying mostly on the SFF reservation. Several other people have noted something to the effect of, “Poul was so good at so many things, we kind of took him for granted.”

-

Yes, Poul Anderson really didn’t get quite the kind of recognition he deserved. Oh, he got recognition – but I’m not sure, from what I’ve read, that anyone really quite grasped what amazing range he had.

-

-

Haffner Press recently published a massive two-volume collection of all of Fredric Brown’s stories from the detective pulps. I’ve been meaning to get them, and I may break down and do so.

I hadn’t heard the term siloing before, but it really fits what has happened in the publishing business. I know as a writer I’d go crazy if I had to write in the same genre, or even the same sub-genre, all the time. I’d rather write it all!

-

You, Mr. Reasoner, are one reason the Western fiction market is still close to it’s pulp roots. Are you still on track for a million words of fiction this year? It’d be a shame to break your streak.

-

I’m more than halfway there, so I’ve at least got a shot. All I can ask for, really. I’d like to hit that mark this year and a couple more, and then maybe slow down some.

-

Slow down?!? It’s only a million words a year. 😉

Keep showin’ the greenhorns how it’s done, Jim.

-

I noticed her command of story beats, pacing, narrative threads, etc. reading Brackett’s longer fiction for the first time.

https://everydayshouldbetuesday.wordpress.com/2017/06/01/throwback-sf-thursday-the-secret-of-the-sinharat-people-of-the-talisman-leigh-brackett/

I’ve also noticed that modern thriller writers tend to be much better at this stuff than modern SF writers.