Pink Shirt Propaganda vs. Blue SF/F Storytelling

Sunday , 16, November 2014 Uncategorized 11 CommentsPink vs Blue: Which side of the force are you?

[Photo by Gerry Lauzon]

Castalia blogger Daniel Eness has a great post breaking down the differences between Pink and Blue Science Fiction and Fantasy. If that sort of thing interests you, check it out and meet me back here.

I would like to focus on his third point:

[Pink Sci-Fi/F] consciously elevates current progressive ideology above story, plot, and characterization. The personal is the political and the propaganda is the plot.

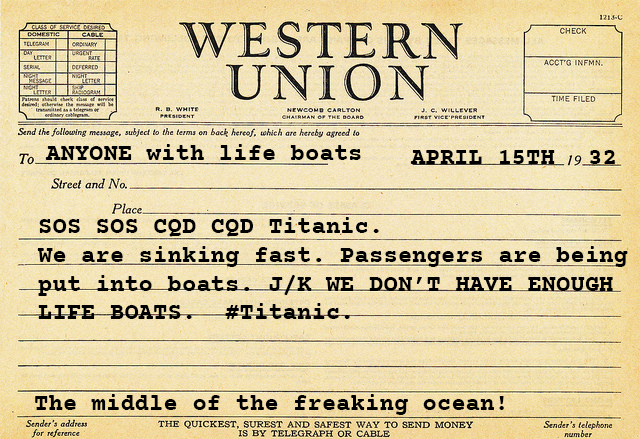

There’s an old movie adage from screenwriter William Goldman that goes “if you want to send a message, use Western Union.”

Unless you’re the Titanic.

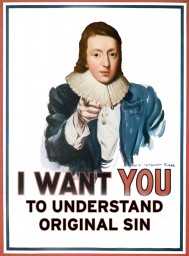

A lot of good writers share Goldman’s aversion to having a clear-cut “message” highlighted, underlined, and bolded in their fiction. In this respect, the pink-shirts are more like evangelists than entertainers. There’s a reason why some Christian filmmakers have a reputation for their slipshod craft, histrionic acting, sanitized characters, and saccharine plots. I mean, check out the trailer to this King David film.

They spent $50 million dollars on that.

No matter how wonderful or important the message, when the storytelling is disregarded in favor of heavy-handed moralizing, the audience tends to check out (and the message is lost). Better to leave the preaching to the preachers.

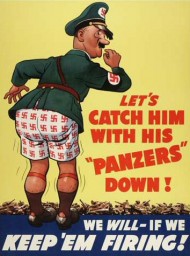

And the propaganda to General Motors

Stories designed to entertain should first and foremost entertain. Boys don’t read science-fiction magazines under their covers with a flashlight at night because they enjoy ambiguous gender pronouns.

“Whoa! That neologism speaks to our hidden cis-male biases!”

Ok, but what about the theme?

Isn’t the theme of a work of fiction a kind of message the author wants to impart to his audience? And what is the goal of propaganda but to influence the attitude of a population towards a cause? Milton wrote Paradise Lost so he could “justify the ways of God to men,” and yet few would argue that Paradise Lost is propaganda.

So what’s the difference between propaganda and theme?

So what’s the difference between propaganda and theme?

Here Daniel again makes another distinction:

[In Pink Sci-Fi] the theme and plot don’t simply harmonize, nor do they echo one another. They are one and the same.

This is basically the definition of a fable or parable – stories whose plots are mirror reflections of a certain moral or teaching. Rachel Swirsky’s Hugo Nominated If You Were A Dinosaur, My Love even has an anthropomorphic animal.

Which is all well and good – Jesus spoke in parables and kids enjoy Aesop. But parables are supposed to be short. Most people don’t want to read a fifty-thousand word fable. Hence, the declining SF/F sales.

However, as Daniel’s post illustrates, the opposition to pink sci-fi doesn’t just come from a ham-fisted one-to-one relation between plot and theme, or being unable to imagine a world that is not a multicultural utopia. Those are artistic concerns that could (in theory) be shared on either side of the divide. No, the opposition is also directed towards the political correctness and overwhelming deviant imagery suffused throughout their works.

Exhibit A

While these features are window dressing to the meaning embedded in the overall story, they tend to be the most effective tactic in promoting the pink-shirt agenda. “Repeat a lie often enough,” and all that. Nonetheless, a writer seeking to subvert Christian morality need not feature a single shapeshifting transsexual atheist to do so.

The devil is even more subtle than this

To take a non sci-fi pinkshirt example, the “pro-marriage Christian” film Fireproof undermines nearly every New Testament teaching on marriage. Call it the “hiding the pink shirt in a blue box” strategy.

Here’s the good news.

Pinkshirts are mostly too intellectually turgid to make a case for the other side, and can rarely resist the temptation to use the soapbox. Great stories, the ones that stand the test of time, are multi-sided grand arguments about the human condition that consist of a combination of character, plot, setting, theme, and genre. Their meaning and their beauty is derived from the way in which those elements combust and resolve.

Big ideas, solid craft, and a compelling narrative will always triumph in the end over political agitprop.

I have argued long and hard and usually to no avail that Avatar’s big sin wasn’t being a film that featured capitalists shamelessly exploiting a resource and trammeling noble savages; its sin is that the story was dreadfully boring because it never bothered to introduce complexity to the equation. I am willing to entertain a story who posits a worldview I disagree with if it does so in an interesting, thought provoking way, say, What if the unobtanium was being used in machinery that was rebuilding the earth’s climate? What if it was part of the anti-xenomorph system that protected all worlds, including Pandora, from acid-blooded aliens? At the end of the day, I’ll still likely disagree with the perspective of the film, but it will at least have made me think a little, and it won’t feel the full force of my loathing.

I’m still in shock after viewing the David & Goliath trailer.

Ed Wood, call your office…

-

I love how they filmed in 2,000 year old plus ruins with the assumption that that’s what they looked like back then.

-

Joshua,

No kidding! And why does everyone have a British accent?

Except Goliath, who’s native tongue seems to be Frankensteinish.

-

Ugh! I said “who’s” instead of “whose.”

Surely the spirit of my sixth-grade English teacher will call on me tonight…

-

-

The problem with Avatar was that the writing was laughably atrocious and the acting was wooden.

“Unobtainium”? Really? That’s like something a hack writes that we all pick out as an example of what not to do.

That is indeed an historic telegraph message. It was sent in 1932, 20 years after the darn ship sank! And we whine because our smart phones won’t survive a dunk in the toilet.

Also, just to be clear, the bolded sections (the ten points) are not original to me. I just used them as the now-standard rubric used to categorize pink fiction.