A. Merritt’s Burn, Witch, Burn is structured almost like a song. Each of the first three chapters ends with its half cadence consisting of either a grisly death or else a stunning revelation. But how exactly do you get to those thrilling crescendos…? There’s the interplay between the tough but superstitious mob boss, the speculations of the insightful doctor, and then the careful skepticism and professionalism of his colleague. Together they harmonize together, explaining and developing the mystery while grounding the horror in real human reactions. It’s masterfully done. And the fact that the vast majority of films and television today lack this sort of cogency only makes it better.

A. Merritt’s Burn, Witch, Burn is structured almost like a song. Each of the first three chapters ends with its half cadence consisting of either a grisly death or else a stunning revelation. But how exactly do you get to those thrilling crescendos…? There’s the interplay between the tough but superstitious mob boss, the speculations of the insightful doctor, and then the careful skepticism and professionalism of his colleague. Together they harmonize together, explaining and developing the mystery while grounding the horror in real human reactions. It’s masterfully done. And the fact that the vast majority of films and television today lack this sort of cogency only makes it better.

Just as striking is the sort of cultural furniture these themes are thread between. Not that it’s a surprise that the protagonist invokes Sherlock Holmes when another character makes an unsupported intuitive leap that’s too much for him. It gets better, though:

“There are three ways a person can be killed by poison or by infection: through the nose—and this includes by gases—through the mouth and through the skin. There are two or three other avenues. Hamlet’s father, for example, was poisoned, we read, through the ears, although I’ve always had my doubts about that. I think, pursuing the hypothesis of murder, we can bar out all approaches except mouth, nose, skin—and, by the last, entrance to the blood can be accomplished by absorption as well as by penetration. Was there any evidence whatever on the skin, in the membranes of the respiratory channels, in the throat, in the viscera, stomach, blood, nerves, brain—of anything of the sort?”

Not floored, yet? I didn’t expect so. You and I both are familiar with the famous scene from Hamlet, the play within a play where Hamlet carefully watched his uncle’s reaction. But here’s the thing. How often do you allude to such things in order to illustrate a point? It’s not reflexive to me. And how often do you see such allusions in fantasy and science fiction today…? The most recent example of that I can think of that’s even close would be the Dickens bits from Star Trek II.

So no, that’s not that out there. I do think it odd given the number of people that have insistent to me that pulp stories were kids literature. And I know kids in those days were pretty smart and all. But am I really supposed to believe that this sort of thing is pitched to them?!

There’s more, though:

You remember Longfellow’s lines:

I shot an arrow into the air.

It fell to earth I know not where.“I’ve never acquiesced in the idea that that was an inspired bit of verse meaning the sending of an argosy to some unknown port and getting it back with a surprise cargo of ivory and peacocks, apes and precious stones. There are some people who can’t stand at a window high above a busy street, or on top of a skyscraper, without wanting to throw something down. They get a thrill in wondering who or what will be hit. The feeling of power. It’s a bit like being God and unloosing the pestilence upon the just and the unjust alike. Longfellow must have been one of those people. In his heart, he wanted to shoot a real arrow and then mull over in his imagination whether it had dropped in somebody’s eye, hit a heart, or just missed someone and skewered a stray dog. Carry this on a little further. Give one of these people power and opportunity to loose death at random, death whose cause he is sure cannot be detected. He sits in his obscurity, in safety, a god of death. With no special malice against anyone, perhaps—impersonal, just shooting his arrows in the air, like Longfellow’s archer, for the fun of it.”

Gosh, he did it again. Except this time it’s poetry. And note that this isn’t some sort of literary grandstanding. Merritt here is using a reference to a common culture in order to convey something significant about a particular scenario. It’s as if Arthur Conan Doyle, Shakespeare, and Longfellow could all be taken for granted as being part of everyone’s mental furniture. They’re all familiar and immediately accessible.

I saved the best for last, though:

Everybody comes into this world under sentence of death—time and method of execution unknown. Well, this killer might consider himself as natural as death itself. No one who believes that things on earth are run by an all-wise, all-powerful God thinks of Him as a homicidal maniac. Yet He looses wars, pestilences, misery, disease, floods, earthquakes—on believers and unbelievers alike. If you believe things are in the hands of what is vaguely termed Fate— would you call Fate a homicidal maniac?”

In the first place, I can think of few places that deal in this sort of plain, philosophical reasoning. And the source of the reference points on display here that Merritt and his entire audience could take for granted is of course the bible. (This is a paraphrase or a conflation of Matthew 5:45 and Luke 13:4.)

A. Merritt wasn’t the only pulp writer that did this sort of thing. H. P. Lovecraft, C. L. Moore, and L. Sprague de Camp all did it as well. So much so that you could piece together a fairly respectable canon just from collating a list of the works they refer to. You know who doesn’t do this sort of thing…? The sort of people that write what is referred to as “literary science fiction and fantasy”, who almost to a man will reflexively malign the pulps and the people that wrote them.

Personally, I don’t think it’s fair to really call what they do “literary.” They simply aren’t literate enough to merit it.

Jeffro

I agree

The Romances (chanson de Roland) wwere the pulps of the miidle ages. The conquistadores were stepped in those stories and many place names come from those stories. It’s only been a recent.phemenon to regard pulps as embarrassing cultural

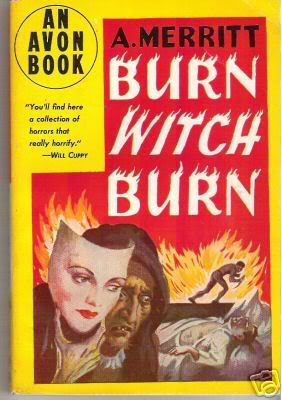

Robert Bloch and Karl Edward Wagner considered BURN, WITCH, BURN to be a classic novel of supernatural horror.

And like I covered in that Seabury Quinn review, lots of allusions to Goethe, Marlowe, and Verdi.

“Pulp not literate.”

“Literary Science Fiction & Fantasy”

What baloney.

Reading the pulps, you get myriad references to history, fiction, poetry, music and myth. Just one example:

In the first 3 Harold Shea stories (The Incomplete Enchanter), Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague De Camp pointed me towards Norse Myth, The Chansons de Roland, Orlando Furioso, Spenser’s Faerie Queen and the Ballad of Eskimo Nell.

Words fail me.

You mean: “Each of the first three chapters ENDS, not “end” with…”

The best writing points you to other authors. (Like Gygax himself did.) Not to other books by the same author and publisher.

“Personally, I don’t think it’s fair to really call what they do “literary.” They simply aren’t literate enough to merit it.”

BRAVO!