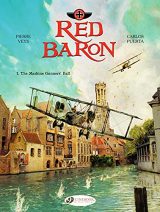

The Red Baron.

The Red Baron.

A pilot of almost supernatural skill. Manfred Von Richthofen’s legend lives forever. But how did such an icon of war get his start? What made him different from his peers? And why was he so fond of the terribleness of war? Perhaps it all stems from a gift–the ability to read other people and discern their intentions. An addictive gift at that, and one that would drive Richthofen to great heights and terrible acts.

Author Pierre Veys and artist Carlos Puerta add a touch of the monster to The Red Baron: The Machine Gunners’ Ball. The story settles on three important vignettes: the discovery of Richthofen’s ability to read others, Richthofen seeking out street toughs to practice his newfound skill upon, and Richthofen’s first aerial duel. As the reader progresses through each, Richthofen’s lust for battle and control is illustrated with precise strokes.

For it is the watercolor art that carries this war story. Soft, idyllic, and impressionistic when portraying the illusions of a gilded society. Harsh and photorealistic when violence–or Manfried’s lust for control–smash those illusions. Stunning art only sparsely interrupted by dialogue. While many bandes dessinees revel in the high quality of the genre’s art and artists, few are confident enough to turn over storytelling to wordless action and reaction and the quiet majesty of ink and paint. The Red Baron plays to the strengths of the canvas, addressing harsh realities of war without reveling in gore and shock

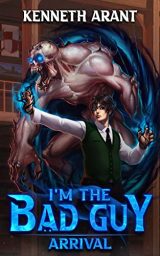

What if you woke up and found yourself in another body? Say, the villain of your favorite magical academy anime, doomed to exile, penury, or worse at the end of the season? What would you do to prevent being railroaded into such a fate?

What if you woke up and found yourself in another body? Say, the villain of your favorite magical academy anime, doomed to exile, penury, or worse at the end of the season? What would you do to prevent being railroaded into such a fate?

This nightmare is common to young women in certain genres. Now it’s the guys’ turn.

In I’m the Bad Guy!? Arrival, by Kenneth Arant, the Princess Improvement genre leaps across the Pacific—and lands on some poor dude’s shoulders instead. Awakened into the pudgy cowardly villain’s body at the age of twelve, the new Aren Ulvani, blessed with the foreknowledge of his doom, must now find a way where he can survive past graduation without running afoul of a protagonist that outclasses himself in every way.

The result is something akin to the same path Aren’s sisters in the genre take: relentless self-improvement. But where Katarina and her fellow princesses focus on improving their situation by improving others’, and thus relying on powerful friends and allies to save them, Aren trusts instead in his own strength. This walls off the charming comedy of errors and misunderstandings that make the princesses’ improvement so delightful, leaving Aren to tread the familiar path of the boyish fantasy hero. And while Aren is a serviceable hero thrust into the familiar fantastic intrigues, he remains a loner. Well, except for the arranged fiancee that comes with the genre. So Aren’s starting conditions may be indistinguishable from the Princess Improvement genre, but the lack of a social network is but one aspect lost in translation from a female-centered fantasy to a male one.

Please give us your valuable comment