This is a fascinating piece of fiction for a good half dozen reasons. Certainly, any Traveller fan worth his salt will be hooked by the second page:

This is a fascinating piece of fiction for a good half dozen reasons. Certainly, any Traveller fan worth his salt will be hooked by the second page:

“I’m glad I never trained as a scout,” remarked Second Officer Walgrave. “Otherwise I might be sent down upon strange and quite possibly horrid planets.”

“A scout isn’t trained,” Deale told him. “He exists: half acrobat, half mad scientist, half cat burgler, half–”

“That’s several halves too many.”

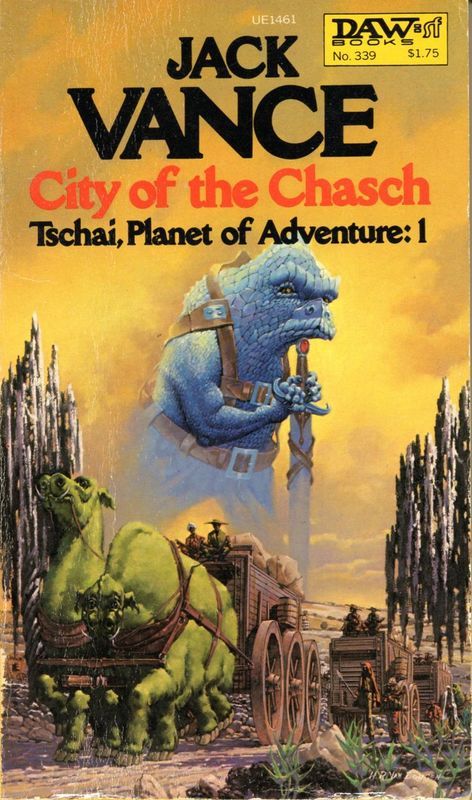

That there is without a doubt the introduction of what would become a cornerstone of science fiction role-playing: Traveller’s scout career. Just as Jack Vance had provided the template of what would become D&D’s thief through Cugel the Clever, here in the pages of City of the Chasch he gives us the iconic Adam Reith: a man of “resource and stamina” and a “master of many skills.”

The scout service of Vance’s universe is just as deadly as that of the Traveller game, too: one of them dies in the first chapter, after all! But referees that have fretted over just exactly the game’s “Jack of all Trades” skill really is supposed to be exactly are in luck, because everything is spelled out perfectly right here:

He had assimilated vast quantities of basic science, linguistic and communication theory, astronautics, space and energy technology, biometrics, meteorology, geology, toxicology. So much was theory; additionally he had trained in practical survival techniques of every description: weaponry, attack and defense, emergency nutrition, rigging and hoisting, space-drive mechanics, electronic repair and improvisation.

Indeed, once your scout has picked up Gun Combat, Electronics, and Engineering, with a level in J-o-T, he should be able to fake that whole gamut of skills there in typical adventuring situations.

Inspiring an element of the Traveller game system is of course something that several books can lay claim to. Like many games of the time, it’s a bit of a Frankenstein’s monster, cobbled together with elements from dozens of “inspirations.” This particular volume goes one step further in that the world that it describes was dropped wholesale into Gary Gygax’s Greyhawk campaign. This is not something I’ve had to painstakingly piece together from eyewitness accounts of the old Geneva gaming group, either. Gygax mentions it right in the game manuals. Just before explaining how to convert Boot Hill characters to and from AD&D, he talks about how the characters in his campaign traveled to other planets– including Jack Vance’s “Planet of Adventure” where they had the chance to “hunt sequins in the Carabas while Dirdir and Dirdirmen hunt them.”

And note that he does this in the same context as Alice in Wonderland, Greek Myth, and King Kong. It’s as if this book were a big deal, on par with the most recognizable properties of literature and film. And Vance was really was that big of deal, dominating the imaginations of fantasy and science fiction fans of his day. This book in particular was so fun, it’s no accident it was among the first things people reached for when the idea of role-playing was brand new and guys like Gygax and Miller were looking for things that would work well at the tabletop.

Revisiting the book today can actually be somewhat controversial in gaming circles, though. In the first place, the more pulpy elements of Traveller’s ouevre have quietly been airbrushed out of the franchise over the years. This style of science fiction is just not how people tend to conceive of the game’s official setting anymore. And people that think of the Greyhawk as being more or less an early iteration of the DragonLance and Forgotten Realms approach to fantasy settings are simply going to go into cardiac arrest at the mention of this title. The tone and style of both Vance and Greyhawk are nothing like that stuff.

How can this overlap between the leading fantasy game of the seventies and the leading science fiction game be explained…? And why does it come off as downright bewildering to people looking back at the earliest role-playing games from the vantage point of today…? Well, there’s a lot of reasons for that. Yes, there was a fantasy and science fiction canon back then. Yes, too, the line between fantasy and science fiction was much more blurry back then. Also, it was normal for the leading authors to write both fantasy and science fiction rather than specializing one or the other. All that aside, the biggest difference between then and now is that Edgar Rice Burroughs was bigger than basically anyone else. Sure, people used to reflexively imitate Lord Dunsany when the got a yen to write the next great epic fantasy. For nearly everyone else, Burroughs was pretty much the definition for how fantasy and science fiction were done.

And this book is basically a case in point for that. In 1968, just a few years before Burroughs would be a central influence on the first role-playing game, here is Jack Vance doing his take on the old Mars stories– the ones that were still hugely popular even though they dated all the way back to 1911. Oh, the planet’s in another solar system and there’s a few tweaks to make the premise keep up with advances in actual science. But there’s two moons, a “fighting man” protagonist, and color-coded humanoid aliens. There’s non-stop, pulse pounding action. There’s beautiful princesses to rescue, multiple times if need be. There are people to liberate. There’s even the incredible uplift project of the Pellucidar series to undertake. Vance’s wit and prose are here in full force, certainly– but nearly every part of the tale is lifted directly out of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s works.

It’s not just the broad brush strokes that are lifted wholesale here, either. It’s the thematic elements as well. Just as you see in Gods of Mars, ludicrous religions used both to enslave and exploit people are tackled head on here. Vance pulls no punches and creates some particularly cutting satire. This stuff is going to be especially striking to gaming fans, because this sort of thing was pretty well purged from fantasy gaming during the eighties. To this day, fantasy religions are typically generic and innocuous. Tame, even. Palladium includes weirdly obsequious warning messages as if someone somewhere might be offended by the graphic depiction of Orc spirituality. It’s as if remnants of the Moral Majority are liable to break in, take our games, and have us cross-examined on episodes of Sixty Minutes at any moment.

Reading Vance though, that weird cultural spasm is unimaginable. And it has that same sort of kick that you get the old pre-code Eerie and Creepy comics, too. You’re finally getting ahold of the unexpurgated variety of science fiction and fantasy! And what’s more, it’s as if there were a time when freedom of expression could be taken as a given. The overall unity of science fiction and fantasy on this point is fairly plain. It’s as if we lost our minds at some point in the eighties, and rather than trying to recover from the damage, we all went off in search of more things to freak out over.

If you doubt that Vance enjoyed more freedom in the sixties than we do even today, then check out his handling of the “Priestesses of the Female Mystery”:

Gala events were in progress. Flames from dozens of flambeaux cast red, vermillion and orange light upon two hundred women who moved back and forth, half-dancing, half-lurching, in a state of entranced frenzy. They wore black pantaloons, black boots and were elsewhere naked, with even the hair shaved from their heads. Many were without breasts, displaying a pair of angry red scars: these women, the most active, marched and trooped, bodies glistening with sweat and oil. Others sat on benches slack and dull, resting, or exalted beyond mere frenzy. Below the platform, in a row of low cages, a dozen naked men stood crouched. These men produced the harsh chant Reith had heard from the hills. When one faltered, jets of flame spurted up from the floor beneath him, and he once more screamed his loudest….

How they hated men! thought Reith. A troupe of entertainers appeared on the stage– tall emaciated clown-men with skins bleached white, eyebrows painted high and black. In horrified fascination Reith watched them cavort and caper and with earnest zest defile themselves, while the priestesses called out in delight.

When the clown-men retired a mime appeared: he wore a wig of long blonde hair, a mask with wide eyes and a smiling red mouth, to simulate a beautiful woman. Reith thought, They hate not only men, but love and youth and beauty!

You know, I can’t imagine seeing something like this in Asimov’s or Analog. It’s completely out of bounds and has been for decades. And again, this is not some from some sort of weird “gentleman’s” magazine, either. This is one of the most influential science fiction novels of the sixties, written by a true grandmaster following directly in the footsteps of the guy whose work not only directly inspired Superman, Star Wars, and Dungeons & Dragons, but who also arguably played a part in getting us to the moon. And that’s really what is most interesting about City of Chasch. It was as influential and inspirational as it was because it hewed so closely to the guy that set the tone for what fantasy and science fiction was in the 20th century.

That’s also the key to the thing that was most baffling to me when I first began looking back at the first wave of rpg designers: how was it that these guys could be so eaten up by all of these obscure authors?! How could they be so consumed with the vision of people that were writing decades before them? Why was it the case that just a short time later, short fiction would be all but irrelevant to culture, inspiring very little in comparison…?

I think the answer to that is clear. The repudiation of Burroughs style fiction that began in earnest during the seventies– and the repudiation even of love, youth, and beauty with it– it was not the next step in the evolution of written science fiction and fantasy. It was the end of it.

Skimming quickly I mistook the lengthy quoted paragraph for an account of a recent Worldcon.

I keed! I keed!

Well done, Jeffro. You’re really doing your best to break the chains of creativity that have lain so long upon our shoulders. I can only speak for myself, but don’t doubt I speak for others when I say it’s articles like this that make me realize that they’ve been there so long, many of us have worn those chains for so long we didn’t even realize they were there until you pointed them out. Really inspirational stuff.

“They hate not only men, but love and youth and beauty!”

I just finished A princess of Mars and this remark seems similar to how John Carter describes the green Martian society.

Where love and family were prohibited.

Also when reading it I was reminded of the plot of Orwell’s 1984. There is no big brother or double speak but the green Martians were in a constant state of war, their society centered around it, and marriage and family were prohibited by law and custom.

Makes me wonder if Orwell wasn’t influenced by Edger Rice Burroughs.

-

Sadly, it was more that Burroughs and Orwell were both inspired by the real world. Societies that insist that individuals belong to the state have always existed, and they have always been warlike. A family will give a man a reason to live and will motivate him to build and plan for the future. Without that a man be counted on to little but fight, and even that usually not well.

Another book to purchase and devour. Keep ’em coming!

Jeffro, I have been amazed by your Appendix N posts. They have been spot on. I dearly miss the old fantasy and science fiction novels of a bygone era. I devoured Jack Vance novels back in the day, and I particularly loved this series.