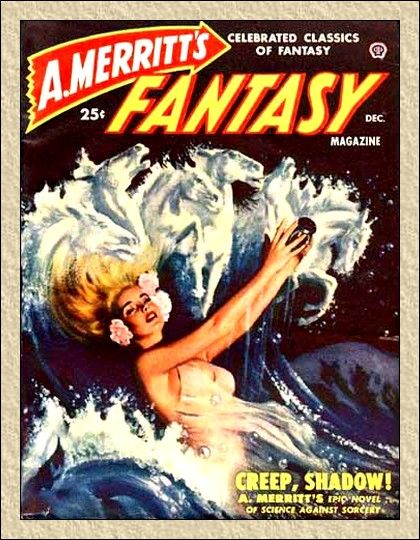

This book is loaded. It’s got seductive shadow women slowly enticing men to commit suicide. It’s got a witch that murders people with her animated dolls. It’s got sketchy scientists, femme fatales, world travelling adventurer types, and even a hard boiled Depression-era Texan. I don’t understand why no one had ever pointed me to this author before now; this is really good stuff!

This book is loaded. It’s got seductive shadow women slowly enticing men to commit suicide. It’s got a witch that murders people with her animated dolls. It’s got sketchy scientists, femme fatales, world travelling adventurer types, and even a hard boiled Depression-era Texan. I don’t understand why no one had ever pointed me to this author before now; this is really good stuff!

It’s got ancient rites, strange cults, god-like entities, and ancestral memories. Most other authors would settle for making a novel out of even just a fraction of this material, but Abraham Merritt keeps piling on the details and expanding the scope. At the same time, the suspense rises inexorably and the pace never seems to slow down. It’s gripping, sultry, spicy, and it never fails to be entertaining. The experience of reading this book seems to transport you inside the world of the old black and white movies. The dialog is crisp and punchy. You can tell that everyone is well dressed, classy, and good looking. And every scene is drenched in a combination of charm and menace.

One of the things I especially enjoy about the older books like this is the incidental things that it lets drop about how life really was back then. Sometimes the characters can telephone, but other times they have to send a telegram or a cable, for instance. But more than just the side effects of primitive or unrealized technology, sometimes little things happen that show just how much culture has changed in general. My favorite bit like that is this scene where the protagonist escapes serious trouble by climbing out a window and down the side of a building. He takes a chance and finally enters a room that looks like his best bet for getting away:

There was a brilliantly lighted room. Four men were playing poker at a table liberally loaded with bottles. I had overturned a big potted bush. I saw the men stare, at the window. There was nothing to do but walk in and take a chance. I did so.

The man at the head of the table was fat, with twinkling little blue eyes and a cigar sticking up out of the corner of his mouth; next to him was one who might have been an old-time banker; a lank and sprawling chap with a humorous mouth, and a melancholy little man with an aspect of indestructible indigestion.

The fat man said: “Do you all see what I do? All voting yes will take a drink.”

They all took a drink and the fat man said: “The ayes have it.”

The banker said: “If he didn’t drop out of an airplane, then he’s a human fly.”

The fat man asked: “Which was it, stranger?”

I said: “I climbed.”

The melancholy man said: “I knew it. I always said this house had no morals.”

The lanky man stood up and pointed a warning finger at me: “Which way did you climb? Up or down?”

“Down,” I said.

“Well,” he said, “if you came down it’s all right so far with us.”

I asked, puzzled: “What difference does it make?”

He said: “A hell of a lot of difference. We all live underneath here except the fat man, and we’re all married.”

The melancholy man said: “Let this be a lesson to you, stranger. Put not your trust in the presence of woman nor in the absence of man.”

The lanky man said: “A sentiment, James, that deserves another round. Pass the rye, Bill.”

And in that one short scene, we gain a vivid glimpse into another world. The hero ends up convincing them to let him gamble with them for a decent set of clothing:

I opened, and the lanky man wrote something on a blue chip and showed it to me before he tossed it into the pot. I read: “Half a sock.” The others solemnly marked their chips and the game was on. I won and lost. There were many worthy sentiments and many rounds. At four o’clock I had won my outfit and release. Bill’s clothes were too big for me, but the others went out and came back with what was needful.

They took me downstairs. They put me in a taxi and held their hands over their ears as I told the taxi man where to go. That was a quartette of good scouts if ever there was one. When I was unsteadily undressing at the Club a lot of chips fell out of my pockets. They were marked: “Half a shirt”: “One seat of pants”: “A pant leg”: “One hat brim”: and so on and so on.

Yes, it’s actually a serious obstacle when the main character ends up in a situation where he might have to hail a cab with torn and disheveled clothing! But the interesting thing about this, it’s not that these ordinary men pitch in to help a guy that is in a tight spot, but that they do it in a way that would allow him to save some face, to feel like he earned it. At the same time, it appears that they are also taking things slow so that they can get a feel for his character. These are regular guys that leave their wives at home so that they can stay up until four in the morning drinking and playing poker, but there is a lot of wisdom and savvy in how they conduct themselves. It’s remarkable.

Another thing about these older books is that the authors seem to really love invoking old stuff. To make something horrific, it appears like they have to go way back in time in order to make it sufficiently inscrutable. Ancient Egypt wasn’t usually remote enough, no– they seemed to think they had to dig further back into prehistory in order to get something truly spooky:

I said: “It would take me days to tell you all the charms, counter- charms, exorcisms and whatnot that man has devised for that sole purpose Cro- Magnons and without doubt the men before them and perhaps even the half-men before them. Sumerians, Egyptians, Phoenicians, the Greeks and the Romans, the Celts, the Gauls and every race under the sun, known and forgotten, put their minds to it. But there is only one way to defeat the shadow sorcery —and that is not to believe in it.”

He said: “Once I would have agreed with you—and not so long ago. Now the idea seems to me to resemble that of getting rid of a cancer by denying you have it.”

Along with that, there was a tendency to play up more rational explanations for the horror elements that the characters come acroos. It’s not so much that the authors are actually going to allow things to culminate into some sort of Scooby Doo type ending. But rather, in order for the characters to have credibility they had to display a certain degree of skepticism as they encounter the supernatural. The way that the author gains credibility at the time was to explicitly tie the story elements into a larger, evolutionary picture. This establishes a more scientific tone while creating an epic sweep to the tale:

“A brilliant Englishman once formulated perfectly the materialistic credo. He said that the existence of man is an accident; his story a brief and transitory episode in the life of the meanest of planets. He pointed out that of the combination of causes which first converted a dead organic compound into the living progenitors of humanity, science as yet knows nothing. Nor would it matter if science did know. The wet-nurses of famine, disease, and mutual slaughter had gradually evolved creatures with consciousness and intelligence enough to know that they were insignificant. The history of the past was that of blood and tears, stupid acquiescence, helpless blunderings, wild revolt, and empty aspirations. And at last, the energies of our system will decay, the sun be dimmed, the inert and tideless earth be barren. Man will go down into the pit, and all his thoughts will perish. Matter will know itself no longer. Everything will be as though it never had been. And nothing will be either better or worse for all the labor, devotion, pity, love, and suffering of man.”

I said, the God-like sense of power stronger within me: “It is not true.”

“It is partly true,” he answered. “What is not true is that life is an accident. What we call accident is only a happening of whose causes we are ignorant. Life must have come from life. Not necessarily such life as we know —but from some Thing, acting deliberately, whose essence was— and is—life. It is true that pain, agony, sorrow, hate, and discord are the foundations of humanity. It is true that famine, disease, and slaughter have been our nurses. Yet it is equally true that there are such things as peace, happiness, pity, perception of beauty, wisdom… although these may be only of the thickness of the film on the surface of a woodland pool which mirrors its flowered rim—yet, these things do exist… peace and beauty, happiness and wisdom. They are.”

“And therefore—” de Keradel’s hands were still over his eyes, but through the masking fingers I felt his gaze sharpen upon me, penetrate me “—therefore I hold that these desirable things must be in That which breathed life into the primeval slime. It must be so, since that which is created cannot possess attributes other than those possessed by what creates it.”

Of course, I knew all that. Why should he waste effort to convince me of the obvious. I said, tolerantly: “It is self-evident.”

He said: “And therefore it must also be self-evident that since it was the dark, the malevolent, the cruel side of this—Being—which created us, our only approach to It, our only path to Its other self, must be through agony and suffering, cruelty and malevolence.”

He paused, then said, violently:

“Is it not what every religion has taught? That man can approach his Creator only through suffering and sorrow? Sacrifice… Crucifixion!”

Now anyone that actually knows anything about evolution should be face-palming at this passage. The whole idea behind the theory is to demonstrate how things could come to be as they are without a supernatural, god-like being creating everything. Interpolating one into the chain of events at any point is ludicrous. Even so, when the theory is described, people all too often fall into the habit of anthropomorphizing the process or else talking about how evolution designed this or that. Still, such talk is entirely believable coming from these characters. This is a common enough error that it’s not that unlikely for them to be speaking this way. By not resorting to the third person omniscient, Merritt is sidesteps a problem that many more famous authors failed to avoid.

Probably the most striking difference between this classic tale and how things tend to be done more recently shows up in his handling of Stonehenge and the Druids. Whenever I see people speculating about that iconic monument, they inevitably mumble something about it’s builders being keen on astronomy. Although some people get into wild theories about space aliens, healing, or ley lines, its actual purpose is generally just regarded as a mystery. Druids are depicted as either zen-like beings with nature-manipulation powers or else as kindly old men climbing trees to harvest mistletoe with their sickles. Creep, Shadow! is downright metal in comparison:

I said: “It may be that they were beaten by the waves against the rocks. But it is also true that at Carnac and at Stonehenge the Druid priests beat the breasts of the sacrifices with their mauls of oak and stone and bronze until their ribs were crushed and their hearts were pulp.”

McCann said, softly: “Jesus!”

I said: “The stone-cutter who tried to escape told of men being crushed under the great stones, and of their bodies vanishing. Recently, when they were restoring Stonehenge, they found fragments of human skeletons buried at the base of many of the monoliths. They had been living men when the monoliths were raised. Under the standing stones of Carnac are similar fragments. In ancient times men and women and children were buried under and within the walls of the cities as those walls were built—sometimes slain before they were encased in the mortar and stone, and sometimes encased while alive. The foundations of the temples rested upon such sacrifices. Men and women and children… their souls were fettered there forever… to guard. Such was the ancient belief. Even today there is the superstition that no bridge can stand unless at least one life is lost in its building. Dig around the monoliths of de Keradel’s rockery. I’ll stake all I have that you’ll discover where those vanished workmen went.”

These people in this pre-Christian cult at the dawn of history, they are not nice noble savages living close to nature without the corrupting influences of modern civilization. They are brutal, dead set on summoning some kind of horrific elder god no matter the cost in blood. Later writers would revamp witches into kindly “wise women.” Vampires would become sparkly and werewolves would become boyfriend material. But in Merritt’s hands, the horrific comes with no chaser whatsoever. Happy earth-goddess people aren’t even on the radar. There’s an edge to this tale that is very appealing.

Edgar Rice Burroughs might seem crude and formulaic to some readers today. H. P. Lovecraft might be a bit dry. And not everyone is the sort to slog through all of William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land. This book by Abraham Merritt is probably a better choice all around for the casual reader that is looking to sample some of the older works. The characters are vividly realized, with human motivations and failings. And the scope of the tale is closer to that of the best science fiction novels than it is to derivative horror movies. Best of all, the horror is a rare combination of the seductive and the deadly. Merritt’s writing is deft and alluring and everything I would expect from the best of the early pulp horror writing.

—

Gaming Notes:

While it would be possible to borrow elements of this book in order to embellish the happenings around, say, the Chapel of Evil Chaos from the classic module B2, the events and characters presented here are beyond the scope of the typical D&D session. As a scenario for something like GURPS Horror, however, this is almost perfect.

There are three major confrontations that would form the adventure structure: the introductory diner encounter, the seduction encounter, and then the final situation at the shrine. There is plenty of material for combat encounters that could terrorize the players before these events as well. With the players working together to hash out a plan together, it actually wouldn’t ruin a session if some of these were allowed to play out with mainly just one player in the spotlight. Still, most of the reworking of the various scenes will be to open things up for allowing several players to engage at once, increasing the number of things that the players could research or investigate between the flurries of action, and restructuring situations so that the outcome depends more on what the players can do and less on any sort of deus ex machina. The tone of the material is far less hopeless than the typical Call of Cthulhu adventure, but most of what’s in this book should be comprehensible even to more casual role players. This could be a lot of fun and the fact that this book is relatively obscure works in its favor for convention play.

Find and read his short story “The People of the Pit” for some extremely effective pulp horror. It’s public domain now. There was even a recent OSR module published on this – “The People of the Pit” by Brave Halfling Publishing.

Merrit is one of those old masters who has sadly faded away after his death…

-

Thanks for that lead. I would never have known otherwise…!

I’m not so sure that the old Darwinian revolution of thought — as highlighted by Lovecraft and many other fiction and non-fiction authors of the late 19th and early 20th century (read also 1911’s La Guerre du feu – fortunately translated into English under the title The Quest for Fire) — would agree with your take on the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection.

Although the materialistic randomness tends to be acknowledged a bit more heavily, it still appears as a false facade for ancient shadows, dark and murky. The rigid sense of true anti-mystical atheism has never been a fun or vivid avenue for most scientific expressions of Evolution. This is true for all but the driest of Evolution’s modern acolytes. Sagan expressed Evolution mystically: as man having “a sense of falling from a great height” and being made of “star stuff.”

That unknown creative “spark” behind Evolution’s remarkable leaps forward have been very fertile ground for some sort of “unseen hand.”

Look no further than Arthur C. Clarke, who probably perfected the scientific apology for Evolution’s “sentinel.”

-

Clarke is the worst one for that sort of thing if you ask me. It’s as if he’s announcing that evolution actually cannot by itself explain anything. Or else that there are no truly interesting stories to tell from a strict evolutionary perspective. It’s the science fiction equivalent of reading an entire “second creative act” as occurring between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2.

-

Well, that’s the truth right there. There are no more “truly interesting stories” to tell from a strict evolutionary perspective, any more than there are “truly interesting stories” to tell from a strict snake oil perspective.

Yes, you can write stories about snake oil salesmen and people who fall for them, but you can’t write a true story about phony snake oil providing scientific benefit. The story won’t make any sense at all.

In other words, Julien Jaynes was right: Darwinism as de facto science law has been dead for a long, long time. Lovecraft could not have written Rats in the Walls (in something like 1925) had his understanding of science been less complete, and his recognition of “animal spirits” in the horror of evolution less profound.

In other words, if Darwinian science and the dream of Evolution were so natural, its proponents would never dream of making drama out of its corrupt and manipulated nature. Yet, those stories are the rule, not the exception. I can’t even think of an Evolution-based piece of scientific fiction that finds fertile territory in the random.

-