RETROSPECTIVE: Dwellers in the Mirage by Abraham Merritt

Monday , 26, January 2015 Appendix N 8 CommentsA. Merritt is easily my favorite of the early pulp writers. His descent into obscurity since his heyday might be hard for me to fully comprehend sometimes, but it makes me relish his works all the more: it is as if his books are a secret that I practically get to keep all to myself. I am not alone in my admiration of his works, of course. He was highly regarded by H. P. Lovecraft and played a significant role in the development of the much better known Cthulhu Mythos. Merritt ranks highly among the influences that Gary Gygax cites as being the inspiration for the game Dungeons & Dragons. Finally, James Maliszewski even created his megadungeon Dwimmermount as a tribute to the man. So while admirers of A. Merritt today are fewer in number, they are at least in good company.

While the overall structure of Merritt’s work is (in keeping with its time) more or less derivative of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s winning formula, his execution is nevertheless impeccable. All of the standard tropes are here in all their glory with not a hint of irony: the best buddy Indian sidekick, the cosmic terror, warrior women, a “witch woman” femme fatale, and even the eligible “princess” type that just so happen to be living among doughty goodhearted savages. It’s a potent conglomerate, vividly described and masterfully paced; this volume in particular is positively transporting.

I actually even prefer this over Burroughs and Lovecraft. The former strikes me a being a bit cavalier and rough around the edges no matter how much of a debt Merritt might have owed the man. And though the latter is rightly regarded as a grandmaster of horror, his characters are generally well insulated from strange phenomena they encounter. They will follow a trail of unsettling hints for pages on end, all the while remaining in full skeptic mode. Sometimes they insist on a rational explanation of all the strange stuff they find right up until the very end. But usually, one good whiff of the horrors that lurk just outside the collective consciousness of mankind sends them scuttling back to Miskatonic University to foist a massive cover up on the rest of us.

Merritt, in contrast, is much more familiar with his readers. Rather than keeping you at arms length with an formal academic account that carefully lays out all the facts, he puts you inside the head of a protagonist that is far more relatable. Devices such as hypnosis, past lives, and ancestral memories are perhaps a little hokey, but in Merritt’s hands they are powerful tools that make for a positively intimate encounter with the weird.

This passage is a pretty good illustration of how he accomplishes this:

The high priest touched my arm. I turned my head to him, and followed his eyes. A hundred feet away from me stood a girl. She was naked. She had not long entered womanhood and quite plainly was soon to be a mother. Her eyes were as blue as those of the old priest, her hair was reddish brown, touched with gold, her skin was palest olive. The blood of the old fair race was strong within her. For all she held herself so bravely, there was terror in her eyes, and the rapid rise and fall of her rounded breasts further revealed that terror.

She stood in a small hollow. Around her waist was a golden ring, and from that ring dropped three golden chains fastened to the rock floor. I recognized their purpose. She could not run, and if she dropped or fell, she could not writhe away, out of the cup. But run, or writhe away from what? Certainly not from me! I looked at her and smiled. Her eyes searched mine. The terror suddenly fled from them. She smiled back at me, trustingly.

God forgive me–I smiled at her and she trusted me! I looked beyond her, from whence had come a glitter of yellow like a flash from a huge topaz. Up from the rock a hundred yards behind the girl jutted an immense fragment of the same yellow translucent stone that formed the jewel in my ring. It was like the fragment of a gigantic shattered pane. Its shape was roughly triangular. Black within it was a tentacle of the Kraken. The tentacle swung down within the yellow stone, broken from the monstrous body when the stone had been broken. It was all of fifty feet long. Its inner side was turned toward me, and plain upon all its length clustered the hideous sucking discs.

Well, it was ugly enough–but nothing to be afraid of, I thought. I smiled again at the chained girl, and met once more her look of utter trust. (Chapter 4)

In the Call of Cthulhu adventures I’ve observed, it’s pretty much game over when the players succeed in tracking down the evil cultists. Here… we get all of this as part of the prologue. It’s the opening hook, not the climax! And as you can see, the hero really is a nice guy. He’s a skeptic, cut from the same cloth as guys like Clarence Darrow or Carl Sagan. In a film adaption could even be played by somebody like Jeff Goldblum. If anything, he’s a bit smug: patronizing the religious practices of a less sophisticated people. His reorientation with reality comes swiftly, though. He’s about to find out that life is a lot more complicated than he ever imagined:

On swept the ritual and on…was the yellow stone dissolving from around the tentacle…was the tentacle swaying?

Desperately I tried to halt the words, the gesturing. I could not!

Something stronger than myself possessed me, moving my muscles, speaking from my throat. I had a sense of inhuman power. On to the climax of the evil evocation–and how I knew how utterly evil it was–the ritual rushed, while I seemed to stand apart, helpless to check

it.It ended.

And the tentacle quivered…it writhed…it reached outward to the chained girl…

There was a devil’s roll of drums, rushing up fast and ever faster to a thunderous crescendo…

The girl was still looking at me…but the trust was gone from her eyes…her face reflected the horror stamped upon my own.

The black tentacle swung up and out!

I had a swift vision of a vast cloudy body from which other cloudy tentacles writhed. A breath that had in it the cold of outer space touched me.

The black tentacle coiled round the girl…

She screamed–inhumanly…she faded…she dissolved…her screaming faded…her screaming became a small shrill agonized piping…a sigh.

I heard the dash of metal from where the girl had stood. The clashing of the golden chains and girdle that had held her, falling empty on the rock.

The girl was gone! (Chapter 4)

A protagonist in this situation can’t afford to simply fail a sanity check and then swear off weirdness forever. In the first place, he’s complicit with it, an active participant. He’s partly responsible for the blood on his hands even though he acted in ignorance. Running away isn’t even an option because his destiny is bound up somehow with the horrors that have been awakened. And by the time the action has shifted to being set within the lost world on the other side of a tremendous mirage, the average reader ought to be ready for just about anything. I was not, however ready for this:

Behind her rode a half-score other women, young and strong-thewed, pink-skinned and blue-eyed, their hair of copper-red, rust-red, bronzy-red, plaited around their heads or hanging in long braids down their shoulders. They were bare-breasted, kirtled and buskined. They carried long, slender spears and small round targes. And they, too, were like Valkyries, each of them a shield-maiden of the Aesir. As they rode, they sang, softly, muted, a strange chant. (Chapter 7)

Woah.

You know, my whole life I kind of suspected fantasy and science fiction could be like this. I know we hear a great deal about how films and comic books and novels are across the line for this reason or that. It’s just… I always felt like we were holding back on some level. And it sure seems that our epic movies are missing something these days. Occasionally you get a hint that things were different once– that they’re used to be Amazon women in space and stuff like that. But for a long time now it just seems like people can’t invoke that sort of thing except as a parody.

There’s just something about the old stories that we can’t seem to do anymore. It shows up not just in what’s off limits but in how things from the past get tweaked for present day audiences. Just like Faramir can’t be depicted as simply being more noble and discerning than his brother. No, in the film adaption of The Lord of the Rings he has to trudge back to Osgiliath and come face to face with a Nazgul on a winged mount before he could make the right (but counter-intuitive) choice. Just like Fili and Kili dying in battle protecting the body of their kinsman Thorin can’t be left alone to be what it is but has to be reworked to shoehorn in whatever plot elements people can’t live without anymore.¹ Just like Starship Troopers can’t just be more or less faithfully translated into movie format, but rather has to be turned into a two hour pillorying of crazed warmongers that have to be unfrozen from the sixties just for the occasion.

There’s something to all this and it didn’t just happen. Back during World War II, C. S. Lewis wrote in The Abolition of Man, “we laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.” From a cultural standpoint, we’ve been laughing and sneering for a long time. These now utterly predictable mutilations of classic adventure fiction are a direct result of decades of this sort of mentality. And what are the script writers and directors laughing at when they foist these revisions on us? The capacity of a man to make a sound leadership decision in the absence of an immediate crisis that forces his hand. The fierce loyalty that was once routinely summoned up as a part of Anglo-Saxon family bonds. The dedication and determination of a young man as he strives to become officer material in the midst of a war where humanity’s existence is at stake. What is it about the modern mind that it looks at these things and says, “hey… let me fix that?” What is this impulse that makes filmmakers unable to leave this sort of thing alone? It’s an adventure story, of all things…! Are they really that threatening…?!

I may never completely figure this sort of thing out. And I don’t know why it is, but somehow chainmail bikinis and everything else is bound up in all this. It’s just an armchair observation, mind you… but it sure appears that if you have lots of hot viking warrior women in a story, then this is a pretty good indicator that you’re going to get all that other stuff in there, too. And right or wrong, I just love the Merritt’s audacity in not just having them all be redheads, but having them all go topless in their opening scene as well. It doesn’t come of as some sort of weird fetish like some Heinlein’s later stuff… and it’s not especially lurid or titillating the way Pierce Anthony would have played it. It’s just a fact, and it seems like Merritt could write it that way without giving a second thought to any potential complaints from the peanut gallery.

But these characters aren’t just here to provide a little cheesecake. We do get to see them in proper battle, sure… but we also get to see them endure the harsh discipline of military order. And they aren’t just stormtroopers or video game avatars, either– they do have hopes and opinions of their own. They’re tamped down due to the rigors of their society puts them through, but it comes out before the end. It’s a nice touch as well that these people really do have a severe shortage of men– and not due to some kind of dumb female supremacist ideology, either. The male babies just aren’t being born as much among their isolated people group. These viking-like people have no choice but to impress their women into military service.

Inevitably, this scenario has other implications once our square-jawed protagonist enters the scene:

For the first time I seemed to be realizing her beauty, seemed for the first time to be seeing her clearly. Her russet hair was braided in a thick coronal; it shone like reddest gold, and within it was twisted a strand of sapphires. Her eyes outshone them. Her scanty robe of gossamer blue revealed every lovely, sensuous line of her. White shoulders and one of the exquisite breasts were bare. Her full red lips promised–anything, and even the subtle cruelty stamped upon them, lured. (Chapter 15)

Yeah, she’s stunning. Sure, she’s captivating. And yes, the fact that she is… you know… a witch woman means that she is the last person you’d want to be involved with. But she’s also at the center of the action. To sort anything out, the hero pretty much has to get involved with this character. I just love the boldness of this type of scenario, really. It’s like that time that Kirk ordered the Enterprise across into the neutral zone and Spock (yes, Spock!) had to seduce an attractive Romulan commander while his captain donned a disguise and looted the enemy flagship’s cloaking device. It’s good drama… especially when you get to see Spock (yes, Spock!) confronted about his subterfuge by the very woman he’s betrayed.

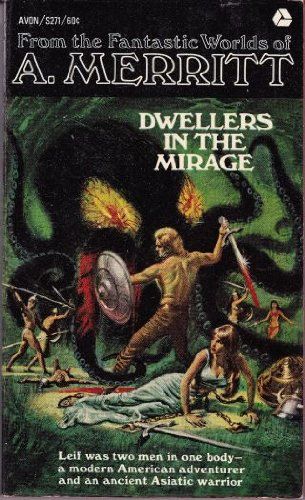

Not everybody goes in for the dashing rogue routine, though. I mean, you naturally look down on a guy that doesn’t even have the option to be a dastardly cad. But when it comes to a protagonist, likability takes a hit if the guy actually goes and takes advantage of someone. At the same time, you wouldn’t be picking up a book with this sort of cover if you didn’t want to indulge in a at least a few scenes of that sort. How can you walk the line between these conflicting constraints…? Well in Merritt’s case, the solution is to have the main character be sort of a reincarnation of that sketchier sort of guy that we’d never really accept in a full-on protagonist’s role. When his “old self” gain’s control of the nice guy’s mind, we’ve got no choice but to read chapter after chapter about the exploits of a top tier scoundrel. It’s positively delicious. And we’ve got enough plausible deniability that we don’t have to feel too guilty about it.

Yeah, that’s a bit of a stretch, sure. But it works… and the whole situation results in some pretty good dialog:

“What have you seen, Dwayanu?”

What I had seen might be the end of Sirk–but I did not tell her so. The thought was not yet fully born. It had never been my way to admit others into half-formed plans. It is too dangerous. The bud is more delicate than the flower and should be left to develop free from prying hands or treacherous or even well-meant meddling. Mature your plan and test it; then you can weigh with clear judgment any changes. Nor was I ever strong for counsel; too many pebbles thrown into the spring muddy it. That was one reason I was–Dwayanu. I said to Lur:

“I do not know. I have a thought. But I must weigh it.”

She said, angrily:

“I am not stupid. I know war–as I know love. I could help you.”–

I said, impatiently:

“Not yet. When I have made my plan I will tell it to you.”

She did not speak again until we were within sight of the waiting women; then she turned to me. Her voice was low, and very sweet:

“Will you not tell me? Are we not equal, Dwayanu?”

“No,” I answered, and left her to decide whether that was answer to the first question or both. (Chapter 18)

Yeah. That’s how it’s done right there.

Of course, you can play your dangerous games like that. But there’s still that part where you come to your senses and get back with the really sweet girl that you should have been with all along. In some ways, that’s a lot more difficult than out playing a player at her own game. There’s something about, oh, I don’t know… selling out your friends, hanging with a really bad crowd, and… oh yeah, hooking up with an utterly evil but smashingly good-looking viking warrior witch woman that puts a damper on things; it pours more than a little ice water on the reunion. How do you talk your way out of that?

Well, if it’s Grant Ward from the “Agents SHIELD” television series, his opening line in a fairly similar situation is, “I figure I let you punch me again, repeatedly.” That is of course brilliant… if you literally want to make someone actually want to punch you repeatedly. Talk about cringe-worthy! And I get that it wasn’t just that he took up with a Norse Goddess there when she mind controlled him, it was the fact that she revealed the truth about who he actually had feelings for. Even so, I could not understand how the scene could make any sense. In what universe does a man owe anyone any kind of apology once mind-controlling secret-divulging Norse Goddesses enter the picture?!

Merritt’s take on this same sort of scenario infinitely more satisfying. The thing is, when your girlfriend actually wants to kill you and she actually has every reason to, and you really were possessed by an ancient warlord that could summon Cthulhoidian tentacles from outside of space and time… well, you’ve got your work cut out for you. Apologies are not enough. Inviting your girl to punch you in the face is not going to fix it, either. First you have to physically restrain her to keep her from killing you… and then you have to put her in a position where she can eavesdrop on you while you start resolving all the remaining plot threads. When she can see not just that the real you is back, but also that your sterling character really is above reproach, well… look out!

“Leif!”

I jumped to my feet. Evalie was beside me. She peered at me through the veils of her hair; her clear eyes shone upon me–no longer doubting, hating, fearing. They were as they were of old.

“Evalie!”

My arms went round her; my lips found hers.

“I listened, Leif!”

“You believe, Evalie!”

She kissed me, held me tight.

“But she was right–Leif. You could not go with me again into the land of the Little People. Never, never would they understand. And I would not dwell in Karak.”

“Will you go with me, Evalie–to my own land? After I have done what I must do…and if I am not destroyed in its doing?”

“I will go with you, Leif!” (Chapter 22)

Okay, maybe it’s not entirely realistic, but it sure makes for a solid conclusion. It is at any rate a story for which I am unapologetically among the target audience of. Sure, this very nearly boils down to being a trashy romance novel for guys. But Merritt’s Leif Langdon is of almost exactly the same mold as Tolkien’s Aragorn: he gets the girl in the end, but he does the things that need doing and preserves his honor in the process. Contrast that with “Camelot” where where Guinevere takes the man she wants regardless of the consequences, openly betraying her husband and destroying the pinnacle of civilization in the process. My old pulp novel collection is positively prosocial in comparison!

More recent iterations of genre fiction really fail to do much for me, though. That “Agents of SHIELD” episode I just mention closes out with the female science expert explaining to the male science expert, “I’m not saying you were weak. I’m saying all men are weak.” (Uh… thanks, I guess….) The male character I most identify with from that series closes out the first season by getting the snot beat out of him by a woman he jilted. It’s almost sadistic how long it goes on. And when trying to pitch the Disney movie Frozen to me, people tell me how awesome it is because the handsome prince turns out to be a real douche bag in the end. As if this were some sort of fantastic literary innovation…! They don’t seem to notice that they are talking to, you know, a bona fide handsome prince type. That’s the kind of character I identify with, after all. And when writers use that stock character as a punching bag and then wipe their feet on him, I take it personally.

Maybe I’ve overlooked the more recent stuff that would be right up my alley, but I’ve got to say that this A. Merritt story really does it for me. When I finish the last chapter and set the book aside, I am positively cheering like the people in all those clips of fans supposedly reacting to the conclusion of the Legend of Korra series. This is the sort of story that has nearly been erased from what is even conceivable anymore… and yet here it is… undiluted… without the slightest hint of snark or self-consciousness. I love it. Maybe I’m a hopeless romantic or something, but hey… at least I’m not a masochist. Half the time I turn on the television anymore I get the feeling that someone’s working overtime trying to erase people like me from the collective consciousness. I’m sick of it. Until this sort of weird cultural myopia runs its course, I’ll stick with works of guys like A. Merritt.

—

¹ Cirsova’s post The Hobbit 3 & Dwimmermount tipped me off about this latest debacle.

No, man. You are looking at one possible future.

One we’re going to build out of the wreckage of the Great Mistake that was the 20th century. Some people think that 9/11 was the beginning of something. I don’t.

I think it was the end. I think the attempted abolition of man has damn near succeeded, but that is because, as usual, we didn’t fight when we suspected it, we didn’t fight when we were warned, we didn’t fight when we could see it with our own eyes, and we didn’t fight when it came for us.

So, we ceded way more turf than necessary, but the enemy has taken what does not belong to him, and he has fallen asleep now, thinking we’ve been cowed.

But we’ve got this tent-peg in the one hand. And in the other is a hammer.

-

::Playing in the background of your comment, Coby Batty’s acoustic version of “Nothing”::

Sweet. As much as I love Lovecraft’s stuff, it’s his lack of truly adventurous characters that can sometimes give his stories a ‘samey’ feel. Sure, there are some fabulous exceptions, like “the Mound”, but more often than not, the protagonist is the rather asexual and drab Randolf Carter or some stand-in for him.

I need to see if my local pulp store has some of this and trade in all of those awful Jean Auel sequels I have no intention of reading.

How could I have missed this novel from Merritt? Thanks for bringing it to my attention.