RETROSPECTIVE: Kothar– Barbarian Swordsman by Gardner Fox

Monday , 13, October 2014 Appendix N 7 Comments Kothar the barbarian…? From Cumberia… in the north…? A rough and extremely strong mercenary that likes cheap wine and cute serving wenches…? Swears by Dwallka of the War Hammer or other made-up gods when he is angry or startled…? Yeah, this is more than a little derivative. He even wears mail that is described in the stories, but which somehow fails to end up being depicted in the cover art!

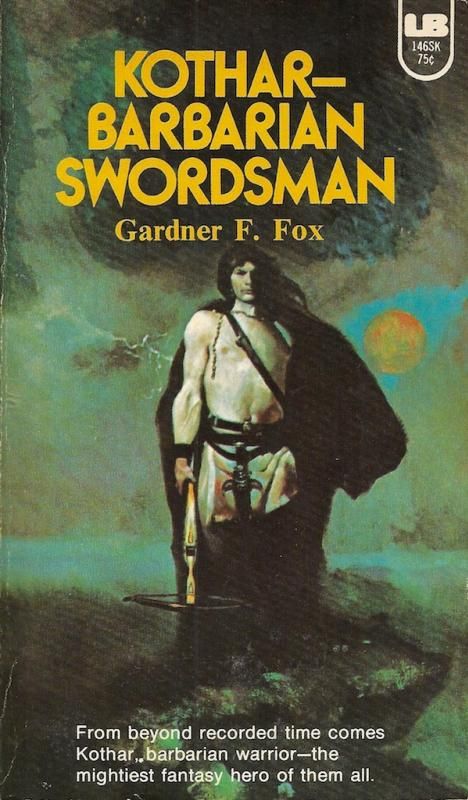

Kothar the barbarian…? From Cumberia… in the north…? A rough and extremely strong mercenary that likes cheap wine and cute serving wenches…? Swears by Dwallka of the War Hammer or other made-up gods when he is angry or startled…? Yeah, this is more than a little derivative. He even wears mail that is described in the stories, but which somehow fails to end up being depicted in the cover art!

Some of the innovations are actually even more grating. Kothars got a magic sword called Frostfire. He’s got his trusty steed Greyling. He’s dogged by random visions of Red Lori, a witch he once double crossed. (If there’s nastiness about, Red Lori makes sure Kothar gets in the thick of it.) But there’s a wrinkle: even though he’s the kind of guy that tackles jobs other adventurers won’t do to win all kinds of fabulous treasures, there’s a curse on his sword: it can only be carried by someone that has no other wealth! Not only does he have overtones of The Lone Ranger and King Arthur, but he’s saddled with an magical impediment that Cudgel the Clever would have defeated in less than half a chapter.

The addition of a cutesy origin story doesn’t do anything to help him, either:

He had always loved the sea– he was spawn of the ocean, having come to Cumberia long ago in a boat as a lonely child– and the smell and fragrance was a stimulant to him.

It sounds almost like a comic book… which shouldn’t be surprising given the author here. Gardner Fox is, as I’m sure you well know, the creator of golden age characters ranging from Hawkman to the Flash. (He even had a hand in creating the uber-cool Sandman.) He created the first superhero team, The Justice Society of America. Later on he got tapped to revamp these properties at the dawn of the Silver Age of comics. He even created the concept of the comic book multiverse when he wrote “The Flash of Two Worlds”, a story where the new Flash teamed up with his golden age counterpart! This lead to the institution of yearly crossovers in the pages of The Justice League of America featuring even more appearances of golden age characters in some truly quintessential tales.

The man is a giant, no doubt. But does anything that awesomeness appear in the pages of his swords and sorcery tales…? Actually, yes. But it’s tucked away in the introduction of this particular volume:

Ages ago, as the legends say, the race of Man knew those stars and all their planets, named and visited them, and left on those planetary surfaces vast cities, great monuments to mankind’s own greatness. Once, uncounted millenia before, and empire of Man was spread throughout the universe. This empire died more than a billion years ago, after which man himself sank into a state of barbarism….

Today, wherever man can be found on the planets of the dying star-suns, the very shape of the continents on which he lives bear little resemblance to those he knew two billion years before. The oceans cover his cities, the desert sands his tombs and temples, while the fierce north wind ruffles vegetation that earlier man had never seen….

And yet– to some men and women who live in the sunset years of the race has been given a power unknown to those men in an earlier age, yet a power famed and feared in the legendry of his people. For there are wizards and warlocks, sorcerers and witches in these days and their spells and incantations are known to work malignant miracles.

The epic nature of this passage is matched only by the disappointment that emerges when the reader slowly realizes that nothing about it impacts anything about the setting or action of the stories. There are no relics of the past, fantastic ruins, or inscrutable artifacts. There isn’t even the strange decadence of something like the Dying Earth stories. It’s just straight ahead swords and sorcery with barely even a nod to the fact that it actually occurs in some Long Night of a sprawling interstellar civilization. Seriously with a setup this cool, I was really hoping to see the freaky alien stuff like what you see in classic Conan stories like “Queen of the Black Coast” or “The Pool of the Black One”, but it just isn’t there!

Fox does at least provide a brief glimpse into how sorcerers conduct their spell research. It’s dimly reminiscent of “The Tower of the Elephant” and is the closest he comes to developing from the really good parts of Conan:

“Long have I sat here in this ancient castle, stripping it bit by bit of all its treasure, paying them over to the wizards and warlocks of the interstellar and intergalactic abysses, that they might teach me their spells and cantraips.

“In a little while I would have been the greatest magician on Yarth! Then nothing could harm m. I have sat here without stirring for these many months. I have studied and learned, and my brain teems with sorceries with which to turn you into a mouse– to drive you mad with unguessable horrors….”

In Fox’s world, magic-users do not automatically gain new spells when they (in essence) level up. They need to settle down into an actual domain so that they can loot it to pay off the wizards of Daemonia for their secrets. In that hellishly bizarre alternate plane of reality, it’s prime surface is seemingly all of water. And it’s loaded with inhuman necromancers that can only be harmed with magic weapons:

An ordinary sword would never have penetrated that purple flesh; only a blade filled with magic could do that task.

The Lich in the first story is also pretty good and fulfills a similar niche:

“In the days when this land was known as Yarth, I was a sorcerer renowned from frozen Thuum in the north to tropical Azynyssa at the equator. My spells could level a city or raise up a tempest on the sea. Even now, after five hundred centuries of sleep, I still come to the call of witch and warlock, to teach the ancient mysteries or to help a suppliant in trouble.”

There’s just three short stories here, but they’re teeming with monsters. Kothar goes up against gigantic white worm-slug, the sea serpent Iormungar, a giant spider, demons, and even the fabled bull-man known here as “the Minokar.” These are all pretty straightforward, though, perfectly at home as fodder for tabletop games. But they do not get near they same kind of introduction, development, description as the ones in Robert E. Howard’s “Xuthal of the Dusk” or even “Rogues in the House.” Next to those, it seems Fox’s monsters are tuned more for action like what you see in four color comics.

Another big difference is Conan ends up in all kinds of situations. He might be on the run from the law and end up on a merchant ship that is attacked by pirates. He might begin a tale on the run after a disastrous battle only to end up exploring a mysterious island with a beautiful princess in tow. He could even be a deposed king, thrown into some horrible dungeon full of abandoned experiments of a wicked sorcerer. Kothar’s more of a one trick pony. He takes on a job with one sorcerer in order to take out another sorcerer. Again and again, even.

Only a fraction of the old Conan stories deal with sorcerers, but that’s pretty much all that’s served up here. And to be honest, I don’t find myself having a reason to want one or the other to come out on top in the end. The scantily clad women that take up with Conan are absent as well, as are the many cultures and nations that are depicted there. This makes the stories seem rather more capricious; Kothar is a pawn for these far more powerful witches and warlocks and he goes from one magical challenge to another. Without a grounding in the human aspect of fully realized civilizations, all of the fantastic elements rapidly become rather arbitrary.

The descriptions of Kothar’s motivations are emblematic of this problem:

He was up and running, bent over, gripping his scabbard with his left hand, regretful that he had not kept on the mail shirt, cursing the streak of romanticism in his nature that made him champion of the weak and helpless, like the Lady Alaine and pretty Mellicent. They were no concern of his; at best, what he did here was only a gamble. He should be galloping for the domains of the robber barons, where money would be easy to win for such a warrior as himself.

Kothar just sort of bops around from one patron encounter to the next. He’s a sucker for a pretty face and he goes hungry because of it. Somehow I have a hard time believing that even if it can be hand-waved due the curse on his magic sword. In contrast, Howard’s Conan is as fully realized as J. R. R. Tolkien’s Gandalf. You can imagine what those two characters would say to questions you might put to them. And in Conan stories, every paragraph is crafted so that his likeability is maintained and contrasted with the crookedness and evil of his foes. When he triumphs, it is positively thrilling to see his more “civilized” opponents get their comeuppance. And the women! Some of Kothar’s witchy woman dream sequences here get perilously close to the sort of graphic luridness that was included in the “Conan the Barbarian” movie from the eighties.

Howard’s Conan stories were racy, sure… but they were never quite that gratuitous about it. And yet, what struck me about the women was just how different they were from each other. Belit treats Conan like a glorified cabin boy when he’s not knocking heads at her command. Yasmela is in a state of abject terror and clings desperately to him for the security he provides. Olivia ends up tagging along out of happenstance and actually ends up rescuing Conan later on. Natala nags and complains, even after Conan goes to great lengths to keep her alive. And so on. These female characters may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but they are characters and they vividly contrast with one another even when they fulfill more or less the same role. You see the same thing with Howard’s pantheon of gods: Crom, Bel, Mitra, and Set are not just swear words! They fully developed fictional deities and they’re an integral part of the cultures of his fantasy setting.

I don’t mind Fox’s Kothar stories. They’re actually much closer to the typical fantasy role playing game scenario because of their simplicity. What bugs me is that the impression that most people have of Conan is that the stories must be every bit as trashy and formulaic as his imitations. That just isn’t the case. And yet, even though the action and the pacing seem to anticipate the sort of typical fare that would become ubiquitous in later role-playing and computer games, there are enough standard tropes missing here that it’s interesting to see how things play out without them. Like an odd reductio ad absurdum, Garder Fox’s small volume of tales demonstrate why Dungeons & Dragons had to meld so many disparate and contradictory themes together in order to get a coherent, playable game.

It was perhaps inevitable that Dungeons & Dragons would reach beyond the tropes of plain swords and sorcery stories. Unrestrained sorcery is thoroughly chaotic and evil; it’s incoherence and randomness make it difficult to adapt to gameplay in a satisfying way. The threat of it makes for good drama, but it’s better if it is partitioned off from the game world even if numerous Lovcraftian cults are at work to aid in unleashing it. It is ironic, but adding Medieval Christian themed clerics and paladins, each specially equipped to counter these forces, actually are the key ingredient that allows for more sorcery-themed foes to be added back into the mix. Tolkien’s fantasy races provide many useful stereotypes that are perhaps more manageable for novices game masters than fully realized and historically accurate cultures. Finally, Jack Vance’s magic system adds playable spell effects and abilities to the game without requiring player characters to sell their imaginary souls for them. Dungeons & Dragons appears at first to be a Frankenstein’s monster of pulp literature fragments, but it turns out that each of these components serve to solve problems that are immediately evident in the adventures of less well known heroes like Kothar.

Do Brak next!

I thought I had read them all. I will have to keep a look out for Kothar, for completeness sake.

-

Man, I hadn’t even heard of John Jakes’s Brak the Barbarian! I wonder why Gary Gygax didn’t include it in his Appendix N list…?

Actually read the Brak novels, and you’ll know. Kothar is to Brak like Conan is to Kothar. But I still remember that I read multiple Brak novels decades ago, so perhaps they were enjoyable boilerplate stories…

-

Aha, well Moldvay thought enough of Jakes to include him in the list of fantasy authors in his edit of the Basic D&D set.

I always enjoyed the Brak stories. I reread them last year and thought they held up pretty well. Brak is more of a hick than Conan and tends to get banged up more. I am easy to please when it comes to Sword and Sorcery. I just want spectacle and some action. When REH can elevate it to the sublime then all the better. But I will take Robert Jordan Conan over newer fantasy anytime.

One of the more memorable characters I’ve had the pleasure to witness at the table was Lothar of the Hill People.

Yes, with his personality ripped straight from the iffy SNL skit in the 80s. Which was, itself, some sort of riff off of stereotypical epic barbarians.

Derivation done well is its own reward.

Well I liked Kothar. And I have read many barbarian series. Conan, Brak, Thongor, all are great. Kothar can take his place besides any of them.