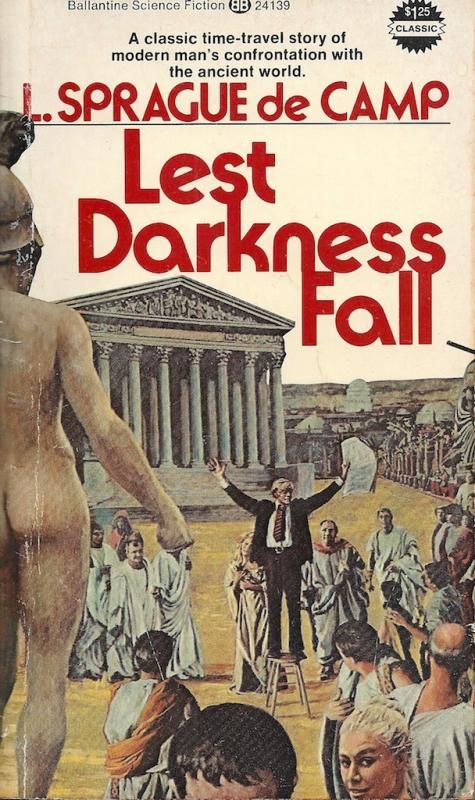

RETROSPECTIVE: Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp

Monday , 9, February 2015 Appendix N 18 Comments It’s a perfectly reasonable impulse to want to have your own favorite volumes of iconic fantasy literature retroactively included in the Appendix N book list. Indeed, it was not surprising to see a few glaring omissions addressed in the latest edition of Dungeons & Dragons.¹ That said, I’m generally flabbergasted when the discussion turns towards who should get booted from one of gaming’s most notable honor rolls. Roger Zelazny gets brought up in spite of the wide ranging appeal of his Amber series– a series that inspired one of the most innovative roleplaying games around! (Amber Diceless, naturally.) Gardner Fox, too, is brought up even though he created the Lich– easily one of the most significant D&D monsters that wasn’t inspired by those weird plastic toys from Taiwan. John Bellairs gets mentioned here in spite of his hilarious anachronisms and compulsive readability. Most surprising to me, however, is to see L. Sprague de Camp’s work singled out for a place on the chopping block. That’s really shortsighted, though. The guy covered a great many things that are of especial interest to gamers– including some things that they consistently neglect. Cutting de Camp out of the Appendix N library does a great disservice, both to him and to gamers in general.

It’s a perfectly reasonable impulse to want to have your own favorite volumes of iconic fantasy literature retroactively included in the Appendix N book list. Indeed, it was not surprising to see a few glaring omissions addressed in the latest edition of Dungeons & Dragons.¹ That said, I’m generally flabbergasted when the discussion turns towards who should get booted from one of gaming’s most notable honor rolls. Roger Zelazny gets brought up in spite of the wide ranging appeal of his Amber series– a series that inspired one of the most innovative roleplaying games around! (Amber Diceless, naturally.) Gardner Fox, too, is brought up even though he created the Lich– easily one of the most significant D&D monsters that wasn’t inspired by those weird plastic toys from Taiwan. John Bellairs gets mentioned here in spite of his hilarious anachronisms and compulsive readability. Most surprising to me, however, is to see L. Sprague de Camp’s work singled out for a place on the chopping block. That’s really shortsighted, though. The guy covered a great many things that are of especial interest to gamers– including some things that they consistently neglect. Cutting de Camp out of the Appendix N library does a great disservice, both to him and to gamers in general.

You see, Lest Darkness Fall is a tale of inadvertent time travel that’s loaded with stuff that can help you bring the oft-shortchanged domain level of play to life. Not sure what to do once your kingdoms are all set up and ready to go…? Why not follow de Camp’s lead and have emissaries from the surrounding kingdoms come calling one after another to demand their piece of Danegeld? If the player chooses to pay them all off, he’ll bankrupt himself. If he gives them all the brush off, then he better be ready to fight them all… simultaneously. (And of course… if the player chooses to ally with one power in order to crush another… his hardscrabble alliance of “free peoples of the West” will just have that must less materiel when the beastman armies crash the big board a few strategic turns later…!)

What about stuff like gadgeteering, inventions, and spell research? This book highlights exactly why it is that Gary Gygax would write “YOU CAN NOT HAVE A MEANINGFUL CAMPAIGN IF STRICT TIME RECORDS ARE NOT KEPT” in all caps in his Dungeon Masters Guide. Sure there are plenty of game changers that you can conceivably whip up. But it isn’t going to come together overnight. Not every project will come to fruition. Even the ones that can actually be accomplished are often going to be irrelevant by the time they can actually be brought to bear. And you can’t expect the world to just leave you alone to sort all this out at your leisure.

If you think that every single engineering project you can conceive will play out exactly the way that it did for Captain Kirk when he had to fight that big reptilian Gorn in single combat, then you’ve got another thing coming. Face it, your character is not (in most games, anyway) like that android from David Weber’s Off Armageddon Reef. You don’t have all the recipes for everything all safely backed up in your memory banks. There’s no telling if you could even get the proportions of sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate correct. And even if you did, it’s not a sure thing that you’ll be able to manufacture enough to be useful or that you’ll be able to create an effective killing machine with it on short notice. And even if you could pull that off, do you have enough social savvy to protect yourselves from rivals that can have you brought up on charges of witchcraft for even accidentally insulting them?

And this is the area where Lest Darkness Fall really comes alive. Telescopes, brandy, Arabic numerals, double entry bookkeeping, and Morse code are all well and good. But yellow journalism, blackmail, dirty politics, and down home barbecues are even better– especially if you’re of a mind to take over the ancient world and prevent the onset of the dark ages. The way he writes, it’s pretty clear that if L. Sprague de Camp was a Dungeon Master, charisma wouldn’t be the dump stat that everyone else seems to think it is…! And nowhere is de Camp’s grasp of human nature more clear than in his depiction of our “book smart” protagonist’s encounter with women of the past. It starts innocently enough with a drunken fling with his house keeper:

He moved carefully, for Julia was taking up two-thirds of his none-too-wide bed. He heaved himself on one elbow and looked at her. The movement uncovered her breasts. Between them was a bit of iron, tied around her neck. This, she had told him, was a nail from the cross of St. Andrew. And she would not put it off.

He smiled. To the list of mechanical innovations he intended to introduce he added a couple of items. But for the present should he…

A small gray thing with six legs, not much larger than a pinhead, emerged from the hair under her armpit. Pale against her olive-brown skin, it crept with glacial slowness…

Padway shot out of bed. Face writhing with revulsion, he pulled his clothes on without taking time to wash. The room smelled. (p 82-83)

But as our “skeptical inquirer” type hero continues his meteoric rise in business, politics, and war he necessarily moves on to more attractive prospects. He hits the jackpot, even: he finds someone that is both ravishingly beautiful and able to afford the kind of personal hygiene that could maintain her appeal even to a guy with 20th century grooming standards. She’s better connected than Princess Leia– and even better, her home world hasn’t been blasted into asteroids. And even better than that, she’s she seems to be developing feelings for the protagonist ever since he rescued her from having to be married to a positively odious guy. It’s a classic fairy tale plot point. It’s almost too good to be true!

Mathaswentha sat up and straightened her hair. She said in a brisk businesslike manner: “There are a lot of questions to settle before we decide anything finally. Wittigis, for instance.”

“What about him?” Padway’s happiness wasn’t quite so complete.

“He’ll have to be killed, naturally.”

“Oh?”

“Don’t ‘oh’ me, my dear. I warned you that I am no halfhearted hater. And Thiudahad, too.”

“Why him?”

She straightened up, frowning. “He murdered my mother, didn’t he? What more reason do you want? And eventually you will want to become king yourself–”

“No, I won’t,” said Padway.

“Not want to be king? Why, Martinus!”

“Not for me, my dear. Anyhow, I’m not an Amaling.”

“As my husband you will be considered one.”

“I still don’t want–”

“Now, darling, you just think you don’t. You will change your mind. While we are about it, there is that former serving-wench of yours, Julia I think her name is–”

“What about– what do you know about her?”

“Enough. We women hear everything sooner or later.”

The little cold spot in Padway’s stomach spread and spread. “But–but–”

“Now, Martinus, it’s a small favor that your betrothed is asking. And don’t think that a person like me would be jealous of a mere house-servant. But it would be a humiliation to me if she were living after our marriage. It needn’t be a painful death– some quick poison…”

Padway’s face was as blank as that of a renting agent at the mention of cockroaches. His mind was whirling. There seemed to be no end to Mathaswentha’s lethal little plans. His underwear was damp with cold sweat. (p 145-146)

And there you have it. This is not the over the top idealized presentation of women that you get in a rip roaring Edgar Rice Burroughs novel. Neither is this the “man with boobs” shtick that you see in everything from Chronicles of Riddick to Agents of SHIELD. This is women as they are, with their own ambitions, their own unique strengths, their own passions and jealousies, and their own effortless mastery of intrigue. As enticing as she might otherwise be, our smart aleck know-it-all from the future just isn’t up to the job of dealing with her. (And if you think that all women that predate the suffragettes had to have been passive, wilting violet doormat types, then you clearly haven’t read too many characters cut from the same cloth as de Camp’s Mathaswentha!)

The other thing here is that the author is depicting the ancient world as being one without privacy, without tolerance, without due process, without habeas corpus, and without anything remotely like a principle of “innocent until proven guilty.” Indeed, anyone that grew up in a small town will readily recognize just how potent a force the local gossip ring can be. And in contrast to Robert E. Howard’s vivid portrayal of civilization being set up expressly to pervert justice in favor of foppish nobles over honest thieves, here we see just about everyone as being free game! It’s the “nice” people that especially seem to bring it on themselves. The guy that quietly lets go a workman that is caught embezzling is liable to be brought up on outlandish charges. Jilted lovers and political rivals are equally liable to make false accusations that have drastic consequences. Even bribing the right people isn’t always enough to get out of trouble: the various functionaries and bureaucrats are more liable to fight over who has the authority to torture confessions out of people than see anything remotely like justice served. It’s a mess!

It’s no wonder that the nuances of these sorts of social interactions are rarely dealt with in the average roleplaying campaign. Tabletop gaming is necessarily going to play to its own particular strengths whether it’s looting a dungeon or playing out an epic fantasy battle. And unless they’re Diplomacy fans, the average player of these types of games is going to be of a mind to escape from the kind social pressure that goes with navigating society, establishing a dynasty, and dealing with ostracization. People just like to be able to go into a town in Ultima II and not have to worry about the guards coming after them unless and until they really have stolen something from one of the shopkeepers. Outwitting the shopkeeps in Nethack is a blast, sure, but gamers don’t necessarily want to deal with some sort of shotgun wedding scenario when they come back to town and discover that the saucy tart they met last session is suddenly with child. Neither would they want to put up with every single towns-person not only ripping them off but doling out false accusations to The Watch about the players when they get called on it. Indeed, a town where that sort of thing happens routinely is liable to see every single level zero peasant wiped out when the player characters finally reach their breaking point. Heck, the entire place would get burned to the ground if the players are anything like the people I’ve played with.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. The trick for game masters wanting to invoke culture, society, and local color is to make sure that none of these trimmings are seen as a barrier to the players getting what they want out of the game. If you know for a fact that the players are interested in dipping into domain level play, then marriage, titles of nobility, and land grants should be top the list of things thankful potentates are willing to dole out to adventuring groups that have accomplished deeds of renown. This works equally well in everything from Dungeons & Dragons to Traveller to even Car Wars… and yet it’s not something that people tend to think of when they design adventures or set up campaigns.

Traveller adventurers are generally assumed to be more concerned with making starship payments than setting down roots.² And the default reward for a band of hardened autoduelists is $100,000 in cold hard cash… which will generally be blown immediately for repairs and vehicles that will get used up in the next adventure or battle. Even in Dungeons & Dragons where domain play is an explicit part of the end game, people tend to assume that they have to wait for players to get to the right level before it can start. As if there aren’t jobs for which the only people available for them are the ones that aren’t ready for them, yet…! Part of the friction here is that the very concept of adventure is seen as being at odds with civilization… or at least, something that occurs mostly on its frontier. High society just isn’t always what players are looking for in their flights of fancy– and it’s not what many game masters are used to running, either.

Now, I want to explain how to work around all these pitfalls and tendencies… but first let me explain a general method for running a wide open campaign. What most people do most of the time in a long-running campaign is simply connect one prepackaged module or scenario after another into a loose continuity. The rules are generally silent on precisely how to do this. (Indeed, the rules were generally written before the modules were even published!) But even if there is a well articulated default campaign system, it generally gets forgotten or deprecated as the system continues to be developed. The tested and tightly scripted modules are what tends to catch on in actual play, because they give a “good enough” result that requires less confidence, fluency, and specialized knowledge to implement.

Consequently, campaign development rules often end up getting the least amount of development and coverage in classic role playing games. Oftentimes, the gamemaster is presumed to just know what he needs to do– and he’s often expected to just ignore entire sections of the rules wholesale. This leads to a weird situation where campaigning is something people do in spite of the rules under the assumption that everyone else must already be doing it just fine. So here is (completely spelled out) my pointers on running campaigns– this stuff I wish someone could have told me back when I was thirteen years old and had all those endless summers to fill with nonstop game session. After this, I’ll break down my pointers on how to actually get to the domain type game that a lot of us never really got around to doing.

- First, realize that the average roleplayer is looking for a recognizable scenario that he believes he has the capacity to excel at. Put the typical game group in the middle of a wide open wilderness hex crawl and you can expect them to just be at a loss as to what to do. Part of the problem is that there’s often not enough information there for them to make any meaningful decisions. (Or worse, the appearance of total freedom is nothing more than mediocre illusion.) That sinking feeling they don’t tell you about…? It’s usually them dreading the hours of stumping around trying to find where an actual adventure is. I know that the early installments in the classic Ultima series were pretty well built this way and they were kind of a big deal. But at the tabletop with real live players, people mostly want you to help them “get to the bangs”³ instead of playing hide and seek with the fun.

- In the typical fantasy roleplaying game, then, try to open up the game with several adventure hooks right out in the open. Traditionally, you would drop hints and rumors about this stuff over the course of several sessions and the players will gradually figure it out after a half dozen roleplayed encounters in the taverns and so forth. Don’t count on it! While they will find impossible uses for pointless oddments that they pick up from throwaway encounters, taking notes on every nuance of your campaign setting just isn’t that high on the list of things that players like to do. It’s more than likely going to be the game master that will keep up with that stuff via session reports if anybody’s going to do it!

- Explain the adventure hooks out of character and in “meta” terms. You are not roleplaying anything at this stage; you’re helping the players make an informed choice that will ensure they get the sort of gaming in that they are looking for. Have some variety, too. You’ll more than likely have the usual dungeon within a days march from the frontier outpost, sure. You’ll have indications of potential standalone encounter situations at varying distances from home base. You might even have adventure situations that are a month’s travel away or more. With all of these, you’ll be able to come up with in-game justifications for whether or not you’ll actually play out the journey according to your system’s specific game mechanics. Note that if you are insisting on playing through piles of random encounters like that, you’re off the hook for prepping in advance very much the adventure that awaits the end of the journey! And when you rough out a dungeon and the players drop down to a new level faster than you expected, all you really need is a decent random encounter table to let you wing it.⁴ (Hint: make the fight tougher than average so that the players are tempted to run away or at least go back to town immediately following it.) Having lots of things for the players to do does not mean you necessarily have tons of upfront planning to do.

- Another thing you’ll want to pay attention to: in addition to having a variety adventure types, you’ll also want to have a range of difficulties on the list of available options. Some of them should be so obviously hard that the players all scoff at them. The old text adventures by Scott Adams and Infocom are great examples of this. Those progammers understood that you could really hold someone’s attention if you taunt them with something impossible while at the same time giving them a range of things scattered around for them to tinker with and solve in preparation for dealing with the real challenge. Enchanter, Zork, and Adventureland are all masterpieces of the form for just this reason. When the players come across the key to something that has stymied them in the past, it creates this great “eureka!” moment. Confronting the players an insanely challening problem early on also reinforces the idea that every single encounter is not designed from scratch to be a self contained easy win.

- For each of your adventure options, there needs to be something at stake and there needs to be consequences for the campaign state in that follow from how they are engaged with and/or resolved. Ignoring things can have consequences, too. It might be a good idea for the players to pass on messing with the dragon that lairs a hundred miles away when the party is weak… but dealing with it may become a much more pressing matter when a witchking arises in a neighboring domain that knows how to put that monster to strategic use! This one point is the thing I find the least acknowledgement of in all the old gaming books. I don’t think I’ve ever read any roleplaying game designs that actually even acknowledged that campaign state was even a thing. I know that with dungeons where the players are making multiple trips there, I tend to have the various monster tribes adapt to the players tactics over time. (Kobolds killed so many player characters in one game, they actually became the general store for all the other monsters– trading all this iron spikes and torches for whatever else they needed.) You need to do something similar with the situations at the villiages and castles the players come across. Basically for each major encounter or scenario, there needs to be some sort of consequences that ripple out into the setting and the non-player groups, both civilized and not. When you place any sort of adventuring situation into your campaign world, you’ll want to have some kind of notion of reasonable consequences for a range of outcomes, both successful and otherwise.

- If this sounds like a lot to keep up with, don’t sweat it. Classic introductory modules like B2 “Keep on the Borderlands” and X1 “The Isle of Dread” are already set up exactly how I describe here. The only thing I’m doing that’s different here is explaining how to frame these big jumbles of adventure opportunities so that the players are aware of just how much they can do! Running the game isn’t that hard. Convincing jaded players that actually have real autonomy and that they really are gaming in a “living” world… that’s the hard part. You can give that to them and they still won’t see it– they’ll often make a beeline to the thing that they think they are “supposed” to do, never realizing the potential of classic roleplaying games! That’s part why you give them brief out of character rundowns of everything and give them straight answers about the relative stakes and difficulties and formats. It does come off as a bit like the old “Choose Your Own Adventure” books, but it allows them to see what you’re offering them instead of what they assume you’re offering them.

- Another thing to keep in mind is that you’ll often see things in the older adventure designs that are regions that are intentionally left vague and undeveloped. This is for a darn good reason. Some game masters think they’re so smart because they have this idea of dropping the B1’s “Caverns of Quasqueton” in as module B2’s “Cave of the Unknown.” Fight that impulse! In the first place, you need to have the sort of confidence that will allow you to (among other things) portray a random keep without going through the hassle of working out every last floor plan for the place. (You laugh, but Traveller referees get caught up with that except that in their case they’re detailing dozens of worlds at a time!) Mainly, though, you need to leave the blank spots blank because you’re going to need something totally unexpected once the campaign gets started and these undetailed regions are going to be the perfect place for them to emerge. Think of it as “just in time adventure design” based on requirements that are discovered in the course of play!⁵

- You’ll notice that I haven’t talked much about your sweet setting background and your awesome cast of non-player characters. There’s a reason for this: everybody hates your stuff. It’s not you. Really, it’s not. It’s just that players care about your campaign setting only so far at serves up adventures that they want to play. All that continuity stuff that you fret over… nobody cares. The longer you talk about it the more you sound like a pitiful wannabe novelist. And your mary-sue characters? The players would kill them in a second if you didn’t make them stupidly powerful. Even the barkeeper and stable boy are just seen as knuckleheads that are keeping the players from getting to what they want by sitting on crucial information. Quit that! Oh, sure, the players will tease you when you make up a silly name for a character on the spur of the moment, so have a list of good ones handy to draw from during play. But they need personalities only so far as it facilitates the game. If these characters take on a life their own in the course of play, so be it… but they are not the best place to dedicate your prep time. Good strong archetypes– clichés even– are the way to go because the players will know what to do with them when they come across them. Really subtle characterizations can be just another form of hiding the fun, so don’t bother getting too fancy with this stuff.

- Most players that have played a lot know that there’s plenty of good reasons to play anti-social orphans that only work with other player characters. The girlfriend characters and the extended family are viewed as liabilities more than anything else– hostages in the hands of the game master to be used to bully the player into doing whatever stupid thing he has in mind. What they are actually doing is fighting the game master in order to preserve their autonomy in the face of his meddling. They don’t like this stuff any more than they like any other kind of railroading. (A lot of this came out of the disadvantage rules from games like Champions and GURPS, but this was actually formalized in Hackmaster. This sort of adversarial stuff is funny… but not for the players.)

- Finally, if you have a crack team of players that engage beautifully with everything you throw at them and that want to pitch in with developing the setting and that really have better ideas about how the game should work than what you have… then definitely, you want to embrace all this and incorporate their contributions as well as you can. You’ll burn out if you try to do it all yourself anyway. Yes, a lot of my advice here assumes that the players are a little more passive, but not every group is like that. If you’re running your game and you’re feeling like you’re having a hard time keeping up with just how awesome your players are, then that is a great place to be. In that situation, your job really amounts to littler more than light refereeing, note taking, and general facilitation then. Go with it! It’s much better than being the guy that is treated like he’s solely responsible for everyone having a good time. As your campaign develops in this direction, what you’ll see is that aspects of various game mastering responsibilities are actually being shared with the players. Don’t forget though that as gamemaster, you are ultimately responsible for the integrity of the game. Answering most player suggestions with “yes” or “yes, but” isn’t going to break anything. But players don’t have access to complete information about the overall campaign state. You still need to retain the capacity to say “no” and to make the call as to whether or not to actually say it. Nothing the players declare or suggest impacts the campaign state until it’s run through an actual ruling on your part.

Now, as you dig through that deluge of points there, you’ll begin to get a notion of why it is that the action in your roleplaying campaigns never quite looks much like what you read about in L. Sprague de Camp’s Lest Darkness Fall. I’m explaining all this so that you understand the panoply of forces that are stacked against your ever getting to something like that. It’s just not how people play by default! And all those gamer friends of yours with dreams of running the perfect campaign with lots of real world history and realistic people…? You know, those guys that never really got a long-running campaign off the ground…? There is a reason why this stuff doesn’t just come together all that often.

If you are really serious about going from having players roll 3d6 in order all the way up to running domain level play incorporating elements ranging from gross injustice, to marriage, and epic military battles, what you need to keep in mind once you’ve already mastered the basics of running a more conventional campaign:

- Do not make the player characters the targets of gossip campaigns, pointless swindles, and backstabbing political maneuvers. Make the non-player characters be the target of that sort of thing and put the players in a position where they can do something about it if they choose. Don’t expect the players to do this out of the goodness of their hearts; reward them with money, information, and patronage if they intervene and do the right thing.

- Do expect the players to resort to violence if non-player characters mess with the players. If the players are more interested in other things and leave hapless peasants and petty nobles to their own devices, then consider increasing a sense of general chaos, but don’t use this as an excuse to punish the players directly.

- If you want the characters to develop a supporting cast of allies, vassals, liege lords, henchmen, and yeah, family, then make all of this stuff be a resource to enable the players to get the kind of game they want. Think of it as sort of a Monty Hall campaign, where all the easy loot is on tap to reward digging into and developing the domain game. Interesting stuff can happen to other people’s family members, sure. But as far as the players are concerned, all of this stuff is a means to getting free land, free help, get out of jail free cards, and plum assignments.

- Do not expect players to run their kingdoms consistently with Medieval or Ancient value systems. If they want real truth, justice, and the American way plastered all over an otherwise realistic historical setting, then let them. (Robert E. Howard let a red handed barbarian pull that off; there’s no reason why your players can’t as well.) If they do go beyond generic justice and order and actually free the slaves, then not everyone will be happy with that, sure. But if you want some background color for just that eventuality, then you can see how de Camp handled that very thing in Lest Darkness Fall if you’re interested.

- Do not force the players to baby sit, manage the farm, or take anything remotely like a day job. Even if they get married or take on a half dozen titles, let them go adventuring if that’s what they really want to do. Take a page from the Honor Harrington series and introduce a steward to manage the estate, a helpful mother-in-law (or witch!) to fill in on the home front, and/or some sort of executive officer to hold down the fort in the player characters’ absence. Domain play is meant to add additional options for play, not limit the players or create a chore for them.

- And yes, these are all options. Domain battles are just one more type of game session and if the players would rather loot a bigger dungeon or tromp a wilder wilderness instead, then let them. Even if the players aren’t interested in messing with their domains directly in actual play, you can add in adventure hooks that have stakes that tie back into their general state and well being. And of course, if someone is more interested in miniature battles would like to step in, you can always (with the players’ consent) let them play out the actual wargames in the party’s place.

- Have the pressure on the players be primarily from external forces. Players will find a use for every conceivable spell, number, and item of equipment on their character sheets if they’re in a tough fight. Put a massive army of beastmen on their borders and they’ll start looking for every possible advantage that they can milk from their domains! (Hint: make the domain status report look as much like a character sheet as you can manage!)

Nothing I’m saying here is all that new, to tell you the truth. I’m just reiterating the standard advice for not railroading the players, not engaging in adversarial play, and not front-loading all of the adventure design. Along with that, I’m also generalizing the basic idea of the “sandbox” to incorporate additional elements that people seem to not get around to playing as much. If this sounds like a lot to take in all at once, don’t panic. Just start with the standard town and dungeon setup and ease into things from there. It worked for Gary Gygax way back in the seventies and it can work for you today! But read this book by L. Sprague de Camp. It’ll help you wrap your head around the sort of things you can do to make the domain game come alive. It’s a good read– and there’s a darn good reason for why it made the Appendix N list in the first place.

—

¹ See Patrick Rothfuss’s Thirty years of D&D for the low down on 5th edition D&D’s “Appendix E”.

² The online JTAS from Steve Jackson Games has an adventure called “The Last Hand-to-Mouth Adventure” by John G. Wood that demonstrated how to transition away from the typical Firefly style campaign setup.

³ This is Ron Edwards’s terminology, which I first saw in his game Sorcerer (reviewed by me here.)

⁴ I am certain that I picked up this tip from a game blog or an issue Fight On! or Knockspell. I’d like to give credit where it’s due, but I just can’t remember who explained this first. (I know this sort of advice was practically unknown when I was trying to run these games as a kid, though.)

⁵ See Lawrence Schick’s post The “Known World” D&D Setting: A Secret History over at Black Gate for a particularly famous example of this technique: We dubbed this setting the “Known World,” to imply there was more out there yet to be discovered, because we didn’t want to paint ourselves into a corner.

I have to admit, I’ve never been a fan of de Camp, but that does sound like a book well worth reading.

As for the 5th Edition, the fact that NK Jemisin is listed in Appendix E as an “inspiration” to the designers doesn’t exactly bode well for it.

-

It shows how far the game has fallen. The original game was far from polished or cohesive except in spirit. The game was about having fun in a fantasy world. The inspirational reading reflected that. Having Jemisin listed reveals what they want you to be doing and it isn’t slaying orcs and gathering loot.

Lest Darkness Falls is easily DeCamp’s best work (from what I recall. It is the only one that of his that made my list of keepers over the years). That being said, his other stories were decent enough to have some inspirational value. LDF has many occasions of the quirky humor that marked his books and can add to a campaign.

-

Sandbox campaigns can be a disaster in computing – there’s no biofeedback when the players tell you it is getting boring – but in tabletop games, remembering a number of techniques like these go a long, long way, especially the bit about not targeting any one player for direct rumors.

Lest Darkness Fall is one of the best stories in the time travel/alternate timeline genre.

The scene with the housekeeper and lice has stuck with me since I was in jr high.

I personally wouldn’t keep the players from being the occasional target of a rumor or orc raid on their holdings. If nothing else it makes for a nice adventure hook. Just don’t over-do it.

LEST DARKNESS FALL is the work that L. Sprague de Camp will be remembered by. THE TRITONIAN RING is my other favorite by him. He constructed a rather good world with his “Pusad Age.” Good enough that others could write or game within it. It was his version of “The Hyborian Age.”