RETROSPECTIVE: “Outpost on Io” by Leigh Brackett

Tuesday , 22, August 2017 Appendix N, Pulp Revolution 2 Comments I recently pointed out how the moral element of pulp-style stories absolutely saturates them, driving not just the structure of their plots, but also defining the likability of the characters on a scene-by-scene basis. I would even go so far as to say that this is what makes old school pulpy thrills even possible.

I recently pointed out how the moral element of pulp-style stories absolutely saturates them, driving not just the structure of their plots, but also defining the likability of the characters on a scene-by-scene basis. I would even go so far as to say that this is what makes old school pulpy thrills even possible.

In the first place, the film I used as an object lesson in this was rejected as not being pulpy enough.

Chris L. wrote in with this: John Wayne saw High Noon as trying to rob the western of heroics. His reasoning was that the Cooper character should have had no trouble getting help (it’s the frontier, and frontiers aren’t for wusses). He felt so strong about the issue that he did Rio Bravo as a counter argument.

Matthew went even further and weighed in with this: I tried to watch this for the first time recently and was surprised to find Gary Cooper’s character despicable. He’s a bully, aloof from the townsfolk, doesn’t go to church except when he needs a posse, tries to recruit in a bar full of the friends of the “bad guys”. Add that to the judge who already had to flee a job in a previous town, and this is clearly the story of rootless cosmopolitan elites who suppress populists.

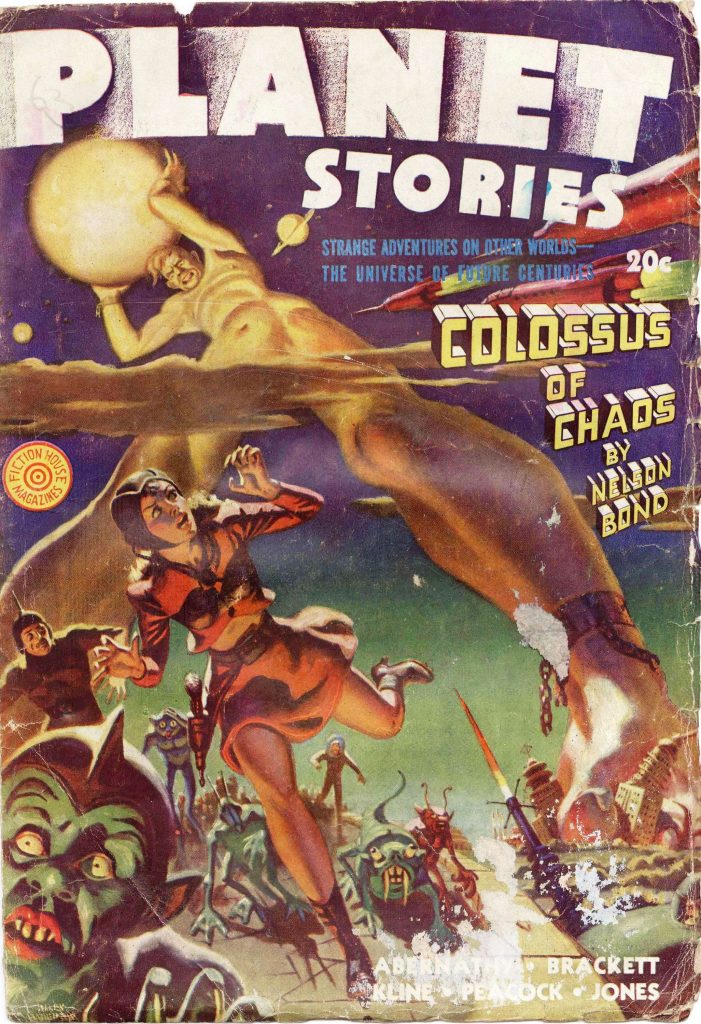

So let’s take a look at how High Noon stacks up against a random Leigh Brackett story. I chose this one because it is the one was referenced in the Did You Just Misgender Leigh Brackett!? story that Alex Kimball broke this past weekend.

(Before I spoil this one, please… do yourself a favor and head over to Luminist Archives and read this one for yourself!)

Okay, what is this story, exactly? Well it’s a really interesting piece for a lot of reasons:

- It’s like a High Noon where the townspeople end up being persuaded to do the right thing at the end.

- It provides the same sort of thrill you get when Han Solo comes blasting straight out of the sun at the climax of the 1977 Star Wars movie.

- It culminates to a very similar situation that you see at the end of Rogue One— but it does so with a coherent plot and likable characters!

Yes, it’s got nonstop action with one fist slinging beat-down after another. Yes, it’s got thrilling locations, weird science, and freaky aliens. But the moral dimension of the work is exactly what gives it its punch and coherency.

Check it out:

MacVickers looked at them, the lines deep in his face. “We all agree, don’t we, that there’s no hope of escape? If we wait until the next supply ship comes and try to take it, we lose the chance of doing– well, call it duty if you want to. That is, to wreck their only source of the explosive that’s winning the war for them.

“I think you know,” he added, “what our chances of taking that ship would be, without offensive weapons or any protection against their’s. It would only mean a return to this slavery, if they didn’t kill us outright.”

His grey-green eyes were somber, deeply bright.

“It comes down to this. Shall we turn this bell into a disentegrator bomb, setting the Jovium free to destroy its own and every other metallic atom in the mud, or shall we gamble our worlds on the slim chance of saving our necks?”

Loris looked down at the deck and said softly, “Why should we worry about our necks, MacVickers? You saved our souls.”

“Agreed, then, all you men?”

Birek looked them over. “The man who refuses will have no neck to save,” he said.

It’s exciting. It’s thrilling. It’s inspiring.

And just like I detailed in my book, it is infused with the same sort of profoundly Christian vision that you find in both J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and (surprisingly) in Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories. Because Leigh Brackett was writing for an audience that understood this:

Then said Jesus unto his disciples, If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me. For whosoever will save his life shall lose it: and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it. For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?

While High Noon is an exciting tale of a man’s man and (ultimately) a woman’s woman, it is nevertheless a story in which the townspeople lose their souls. For someone on the market for undiluted thrills, that’s going to be a real downer. Compared to works by Leigh Brackett and Edgar Rice Burroughs, it’s definitely a step in the wrong direction.

Similarly, the redemption of Han Solo at the end of Star Wars and the redemption of Darth Vader at the end of Return of the Jedi…? That was a huge part of the appeal of that franchise. The jettisoning of this sort of thing by recent installments is a big part of not just why they’re incoherent, but also why Star Wars toys from two years ago are still on the discount table.

“[T]he same sort of profoundly Christian vision that you find in . . . (surprisingly) in Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories.”

Howard’s Conan stories show the influence of the Christian culture of early 20th century west Texas, but I wouldn’t describe them as offering a “profoundly Christian vision” by any stretch of the imagination.