RETROSPECTIVE: Part Two of “The Citadel of Fear” by Francis Stevens

Monday , 8, February 2016 Before the Big Three 2 Comments For all the flack H. P. Lovecraft gets for being a terrible wordsmith, the guy was not dumb. He knew exactly what makes for a good story. He not explained how to do it in a 1920 article for the United Amateur Press Association, but he also put his ideas into practice so well, he went on to enter the canon of science fiction and fantasy as one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. Here is one of his most crucial bits of advice:

For all the flack H. P. Lovecraft gets for being a terrible wordsmith, the guy was not dumb. He knew exactly what makes for a good story. He not explained how to do it in a 1920 article for the United Amateur Press Association, but he also put his ideas into practice so well, he went on to enter the canon of science fiction and fantasy as one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. Here is one of his most crucial bits of advice:

Every incident in a fictional work should have some bearing on the climax or denouement, and any denouement which is not the inevitable result of the preceding incidents is awkward and unliterary. No formal course in fiction-writing can equal a close and observant perusal of the stories of Edgar Allan Poe or Ambrose Bierce. In these masterpieces one may find that unbroken sequence and linkage of incident and result which mark the ideal tale…. The end of a story must be stronger rather than weaker than the beginning; since it is the end which contains the denouement or culmination, and which will leave the strongest impression upon the reader…. In no part of a narrative should a grand or emphatic thought or passage be followed by one of tame or prosaic quality. This is anticlimax, and exposes a writer to much ridicule.

This is not something that Francis Stevens grasped, unfortunately. Not in 1918, anyway. Had she done so, she would have been a household name all through to the seventies right alongside A. Merritt and Lord Dunsany. Instead, she is now less well known than even the most obscure Appendix N authors.

Granted, this second installment of “The Citadel of Fear” is underwhelming precisely because the first part was so good in the first place. There were three separate plot threads, all of which were hitting their respective strides… and I really do wonder how Francis Stevens could come up with stuff this good as early as she did.

There was Archer Kennedy’s journey into the weird, which in places anticipates A. Merritt’s “The Face in the Abyss” and C. L. Moore’s “Black God’s Kiss” even while it touches on themes that Lovecraft would later make famous:

He had feared the hounds and not dared to run from them. Now once more he feared a thought, and from that inescapable pursuer he did run, though not very far.

Meanwhile, Colin O’Hara is faced with the idle flirtations of a goddess:

If you do not care to serve Tlaloc, become the son of Tonathiu, who is sometimes as red as your beautiful, painted hair. Then perhaps I shall marry you instead of Xolotl!”

She said it with the air of one bestowing some incredible hope of favor, but things were moving a little fast for Boots. Lovely though she was, here cold-blooded reference to poor Xolotl’s demise, and her equally cold-blooded annexation of himself, went clean outside the Irishman’s notions of propriety.

“I’ll think of it,” he muttered, and for the first time really gave heed to his surroundings outside the canoe.

Finally, as these two threads come to a head, the status quo of a weird society is threatened:

“If civil war is the result of tonight’s work, you are the one primarily responsible. Quetzalcoatl rules the lake; Nacoc-Yaotl, the surrounding shores. There has always been an undercurrent of rivalry and hard feeling. Why, in past years the guardians, who are chosen from all the gilds and are neutral by oath, have shed more blood policing Tlapallan than in keeping the hills free of invasion….

“Nacoc-Yaotl has horrors in command beyond all thinking by one who has not seen his power. The Feathered Serpent will fight fire with fire, and even the lesser gilds control forces that, if turned loose on the world, might almost wreck civilization. Only the delicate counterbalance of power and certain religious traditions have kept Tlapallan from long ago destroying itself.

When the balance of power in an Elfland is threatend, dreadful consequences can spill over into the wider world. The precise nature of this sort of thing can make for not just mind-bending turns (as in The King of Elfland’s Daughter), but also stakes for sprawling battles at the conclusion of a book– as in this case and in “Conquest of the Moon Pool”.

Francis Stevens takes all three of these threads– all of them building up to fever levels of danger and excitement– and she just walks away from them. She brings one character back to civilization, fast forwards to fifteen years later, and then– in effect– wipes his memory by making him think that all of this adventure was merely “dreams of the delirium”. The net effect is that you start off in one of the best weird tales ever written… and then suddenly find yourself in an episode of Masterpiece Classics. What a letdown!

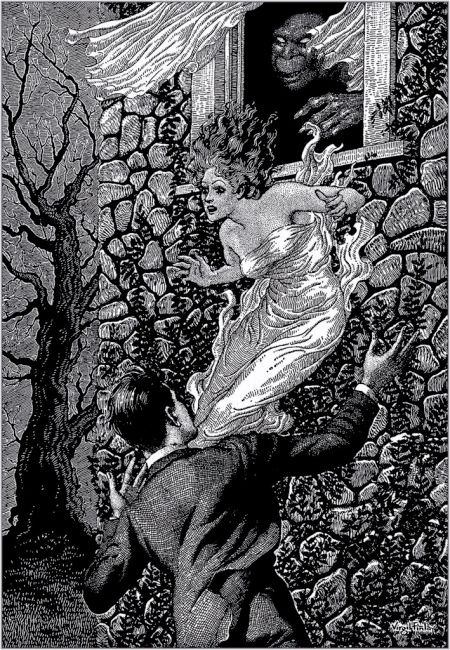

At the same time, in this new stage of the novel the dramatic events move in a decidedly downhill direction. Indeed, the story is no longer about The Citadel of Death. It becomes more about a Bungalow of Terror! With the “terrors” going from what can only be some kind of terrible Lovecraftian horror, to mysterious lights, to a mundane ape, and on to some kind of capricious incident involving a particularly spiteful whirlwind. It’s clearly building up to something, but this is so backwards it turns the book into a a bit of a slog when I was previously hanging on every word.

Compounding things, Stevens never seems to pass up an opportunity to take her protagonist down a peg– to have him “plead against petticoat rule” in front of other men, for instance. After mind-bending adventure, danger, suspense, and excitement… it really is hard to get too worked up over minor domestic crises such as this:

Cliona ceased to speak, and one of those sudden ghastly silences overtook all four of them — the kind that the ideal hostess is supposed never to allow. Cliona wanted to be an ideal hostess — she looked appealingly from Rhodes to Colin.

Now… the introduction of a mysterious woman from Tlapallan is promising, but any significant romantic tension is forestalled by the protagonist’s memory loss leading him to assume that best thing to ever cross his path is suffering from some kind of insanity. It’s too bad, too. You’d think if someone was going to introduce a mysterious elfin woman into a story that they’d milk it for all it’s worth. But Francis Stevens seems to want to pull her punches here.

As a standalone story, this middle third of the book would make for a perfectly entertaining piece of weirdness. Coming directly on the heels of opening chapters, it’s a disappointment. When I first read it, I wondered if this type of story might have been so new it may well have been next to impossible for anyone to guess how best to handle it at the time it was written. On the other hand, if Francis Stevens was ideologically opposed to traditional romance and heroism, she would have been unable to develop her story into anything other than a sequence of anti-climatic letdowns.

This explain so much.

I remember first part of “Citadel of Fear” very fondly. The lake where sun was resting during the night and various horrors were an example of superb world-building. I almost don’t remember the second half of the book. I mean the novel had – probably – an ending but my memory is blank.

-

Jeffro is right: the two parts feel as though they are from entirely different novels. One can imagine a re-written part 2 inserted to better connect parts 1 and 3.

The second half is much tamer and more film noir compared to the first, which feels very tight and well-scripted for an adventure.

If Francis Stevens truly was “ideologically opposed to traditional romance and heroism”, then it’s possible she (a) set up her readers for one type of story in part 1 and tried to pull a twist on a trope in part 2, or (b) didn’t realize that she was following the trope in the first part at all. I’d lean toward the former.

The thing that really bothered me about part 2 was O’Hara’s incomprehensible willingness to take at face value rumor and hearsay *and* one person’s word about the Elf Girl’s insanity, when he doubted everything else that person said and did. Pulled me right out of the book.