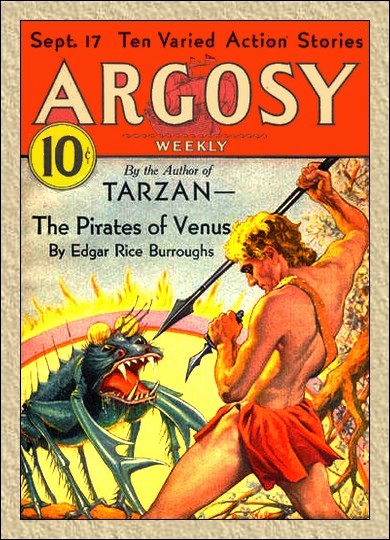

RETROSPECTIVE: Pirates of Venus by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Monday , 8, September 2014 Appendix N 10 Comments At least three of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s series are part of the same continuity: both Tarzan and events from the Pellucidar series are mentioned in this first novel in the Venus series. The Mars series would have been brought in here as well as the protagonist fully intended to go there. Alas, his calculations for his trajectory failed to account for the gravitational pull of the moon. He resigns himself to a slow, ignoble death in the depths of interstellar space, but then miraculously he finds himself hurtling towards Venus instead. “I had aimed at Mars and was about to hit Venus,” Carson Napier admits, “unquestionably the all-time cosmic record for poor shots.”

At least three of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s series are part of the same continuity: both Tarzan and events from the Pellucidar series are mentioned in this first novel in the Venus series. The Mars series would have been brought in here as well as the protagonist fully intended to go there. Alas, his calculations for his trajectory failed to account for the gravitational pull of the moon. He resigns himself to a slow, ignoble death in the depths of interstellar space, but then miraculously he finds himself hurtling towards Venus instead. “I had aimed at Mars and was about to hit Venus,” Carson Napier admits, “unquestionably the all-time cosmic record for poor shots.”

It gets better, though. Not only does Carson Napier survive his unexpected planetfall, but he also discovers a inhabitable world populated by the humanoid Vepagans, which mankind could presumably interbreed with. There are vast stretches of wilderness full of incredible creatures to fight. And though the local civilization has a variety of devastating ray guns, they are in short enough supply that there is still plenty of call for nearly everyone to carry a sword. That’s right, in another incredible coincidence, Mars, the Earth’s Core, and Venus all turn out to have exactly the right conditions for epic romance and adventure. And by a sort of comic book logic, the ramifications of this appears not to infringe upon the ongoing developments back in the “real” world.

Further compounding on the preceding coincidences, the recent history of Venus is strangely familiar:

“Vepaja was prosperous and happy, yet there were malcontents. These were the lazy and incompetent. Many of them were of the criminal class. They were envious of those who had won to positions which they were not mentally equipped to attain. Over a long period of time they were responsible for minor discord and dissension, but the people either paid no attention to them or laughed them down. Then they found a leader. He was a laborer named Thor, a man with a criminal record.

“This man founded a secret order known as Thorists and preached a gospel of class hatred called Thorism. By means of lying propaganda he gained a large following, and as all his energies were directed against a single class, he had all the vast millions of the other three classes to draw from, though naturally he found few converts among the merchants and employers which also included the agrarian class.

“The sole end of the Thorist leaders was personal power and aggrandizement; their aims were wholly selfish, yet, because they worked solely among the ignorant masses, they had little difficulty in deceiving their dupes, who finally rose under their false leaders in a bloody revolution that sounded the doom of the civilization and advancement of a world.

“Their purpose was the absolute destruction of the cultured class. Those of the other classes who opposed them were to be subjugated or destroyed; the jong and his family were to be killed. These things accomplished, the people would enjoy absolute freedom; there would be no masters, no taxes, no laws.

They succeeded in killing most of us and a large proportion of the merchant class; then the people discovered what the agitators already knew, that some one must rule, and the leaders of Thorism were ready to take over the reins of government. The people had exchanged the beneficent rule of an experienced and cultured class for that of greedy incompetents and theorists. Now they are all reduced to virtual slavery. An army of spies watches over them, and an army of warriors keeps them from turning against their masters; they are miserable, helpless, and hopeless. (Chapter 5)

Keep in mind that this was published in 1934, two years after Walter Duranty received a pulitzer prize for his coverage of the Soviet Union and seventeen years after the Bolsheviks had seized power there. When Carson Napier encounters people from the Thorist country later on, it’s clear that the revolution had occurred in their lifetimes just as the October Revolution had occured in Burroughs’s. In his estimation, it’s clear that “the former free men among them had long since come to the realization that they had exchanged this freedom, and their status of wage earners, for slavery to the state, that could no longer be hidden by a nominal equality.” One guy that had been a slave under the old regime admits that he was better off before he got set free by the Thorists: “Then, I had one master; now I have as many masters as there are government officials, spies, and soldiers, none of whom cares anything about me, while my old master was kind to me and looked after my welfare.”

This panoply of impossible parallels is engineered with a single aim in mind: to provide a backdrop for nonstop action. And there is plenty of action here. There are sword fights, ambushes, monsters, winged bird-men, mutinies, boarding actions, and ship-to-ship battles. This book is loaded and the author does not hold back for a second. The approach to setting and plot here is comparable to those of role playing games where ragtag groups of adventurers that have no real reason to cooperate just so happen to run into each other at a tavern where an old man has a perfectly brilliant adventure opportunity. It’s not unlike the iconic Traveller adventure Shadows begins with a random earthquake uncovering ancient pyramids just as the players’ ship is taking off from the planet. When the players investigate, they discover that they cannot leave until they disable the installation’s defense lasers. The players have no choice but to explore this mysterious locale! While it wouldn’t take to much for the average know-it-all to poop this kind of party, most people are willing enough to go play the game that is set before them.

But Burroughs goes far beyond the confines of the typical adventure game scenario, however. The key difference is that when his heroes are dropped into alien world, they generally end up mostly naked. There isn’t any time spent haggling over how they’re going to spend their 3d6x10 gold piece. No, they’re lucky to get a loin cloth most of the time. The other thing that happens is that they immediately pick a faction, form alliances, and then set themselves to the task of reordering the status quo according to their own vision and ideals. There is no angst, no hand-wringing, no self-doubt, not even a quiet desire to just live and let live. The idea of some kind of prime directive where it somehow makes sense for other cultures to learn everything the hard way never crosses the mind of the hero. Edgar Rice Burroughs is the antithesis of Gene Roddenbury.

The third thing in a Burroughs style scenario that is utterly contrary to how things are typically done in tabletop role playing games is the romantic element. No matter how alien the world is, there is always their match for the hero out there among its peoples. Coincidence often thrusts them together, social convention would keep them apart, but the there’s always something more to the hero’s feminine counterpart than mere animal attraction. She’s pretty to look at, sure, but she’s more than just a pretty face. In the Venus series she’s also the last best hope of a world in crisis:

I was still meditating on names in an effort to forget Duare, when Kamlot joined me, and I decided to take the opportunity to ask him some questions concerning certain Amtorian customs that regulated the social intercourse between men and maids. He opened a way to the subject by asking me if I had seen Duare since she sent for me.

“I saw her,” I replied, “but I do not understand her attitude, which suggested that it was almost a crime for me to look at her.”

“It would be under ordinary circumstances,” he told me, “but of course, as I explained to you before, what she and we have passed through has temporarily at least minimized the importance of certain time-honored Vepajan laws and customs.

“Vepajan girls attain their majority at the age of twenty; prior to that they may not form a union with a man. The custom, which has almost the force of a law, places even greater restrictions upon the daughters of a jong. They may not even see or speak to any man other than their blood relatives and a few well-chosen retainers until after they have reached their twentieth birthday. Should they transgress, it would mean disgrace for them and death for the man.”

“What a fool law!” I ejaculated, but I realized at last how heinous my transgression must have appeared in the eyes of Duare.

Kamlot shrugged. “It may be a fool law,” he said, “but it is still the law; and in the case of Duare its enforcement means much to Vepaja, for she is the hope of Vepaja.”

I had heard that title conferred upon her before, but it was meaningless to me. “Just what do you mean by saying that she is the hope of Vepaja?” I asked.

“She is Mintep’s only child. He has never had a son, though a hundred women have sought to bear him one. The life of the dynasty ends if Duare bears no son; and if she is to bear a son, then it is essential that the father of that son be one fitted to be the father of a jong.”

“Have they selected the father of her children yet?” I asked.

“Of course not,” replied Kamlot. “The matter will not even be broached until after Duare has passed her twentieth birthday.”

I was greatly impressed by Dejah Thoris in A Princess of Mars when she was willing to marry an enemy prince just to end the war and save her own people from destruction. The book presented almost exactly the same premise as The Princess Bride, but John Carter’s love interest does something to actually show her character in a good light when she presumes Wesley to be dead. While Duare might do something along those lines in a later sequel, we do not get to see it here in the first installment. Instead, the hero falls in love with her practically at first sight and pursues her relentlessly, directly and arbitrarily. He ends up rescuing her from terrible danger no less than three times: once from violent swordsmen, another time from imprisonment on an enemy ship, and once again from the midst of an ambush by a “a dozen hairy, manlike creatures hurling rocks from slings” and firing “crude arrows from still cruder bows.”

The persistence and repetitiveness of that particular trope is reminiscent of the “plot” of Donkey Kong. To the book’s credit, it never descends into self-conscious parody the way that Dragon Slayer did. The funny thing is, the much maligned “rescue the princess” theme is not something that gets dealt with in the classic tabletop role-playing adventure games. Oh it was right there, hard coded into the role-playing elements of Warriors of Mars. But that merely establishes how Gary Gygax was fully aware of the potential of using this sort of thing even as he passed it over later on in more significant works.

You can see a similar thing happening with the idea of “extra lives” and explicit “respawning locations” that were a fundamental part of Roger Zelazny’s Jack of Shadows. The first text adventures implemented this sort of thing right away and it become an integral part of the later first person shooter games, but in tabletop role-playing games this sort of thing is not directly addressed as an explicit part of the rules. You see, how players create new characters and re-enter an existing campaign is a matter left entirely to consensus and the game master’s discretion. The players will not object no matter how unlikely it is that this new character would just so happen be on hand to join the party’s expedition. Heck, I’ve had people beg to have replacement characters randomly parachuted into odd corners of The Isle of Dread not unlike the way that Carson Napier was introduced into Venus!

Groups of role-players just tend not to have hooking up with a princess on their bucket lists. It’s just not what they’re looking to do when they sit down to throw some dice and eat junk food. Oh sure, someone will always say something ribald to the lusty serving wench. But the stock romantic arc does not mesh well with the needs of a party of adventurers. Superheroes, for example, typically gain a non-powered supporting cast in their individual titles. Spider-man has to choose between Gwen Stacy and Mary Jane. In contrast, Pepper Potts has a major role in Iron Man, but she isn’t generally going to come into the typical Avengers. A romantic interaction that can’t be boiled down to single die roll is just off topic for the typical role playing game. People that demand that sort of thing are like the thief player that wants to by themselves implement outrageously elaborate heists in town when everyone else just wants to get on with the dungeon crawling.

In a similar vein, the default role playing adventurer is simply not cut from the same cloth as one of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s heroes. They are usually brazenly self-aggrandizing, greedy, and cunning– enough so that it is hard to feel bad for them when they come to a bad end. As dashing as they might be, they are ultimately little more than glorified orcs and brigands themselves. The people that play them have no concept of domain level play and therefore find gold and magic items to be far more enticing than any sort of princess. They are generally too fatalistic to think that their actions can have an impact on the game’s worlds or nations.

The space princess was an integral part of the pulp literature that inspired games like Dungeons & Dragons. Indeed, if game designers needed a generic macguffin for the players to go rescue in some wizard’s tower or dark dungeon, they were all happy to swap in an Amulet of Yendor or some such in her place. That sort of thing is easier to transport and requires less improvised dialog, after all. While there might be plenty of reasons that make this quiet omission a good idea, revisiting this particular trope could open up a lot of possibilities at the domain level of play.

“…inhabitable world populated by the humanoid Vepagans, which mankind could presumably interbreed with.”

Burroughs is hardly alone with this type of situation. In fact, it would take quite a while for biology to start quashing this particular trope.

I’ve long wondered if the reason for this is actually the Age of Discovery.

Once upon a time, brave explorers went out into unknown lands. Lands at least as far away (mentally) as Mars was to us a century ago and found—people! Strange looking humanoids that you could interbreed with!

And really, that was the experience of all of history. It seems natural to continue the trend outward.

-

It’s certainly an enduring trope in Star Trek lore.

I do want to reread the mars books to find textual reassurance that Dejah Thoris has breasts. I’m pretty sure her and John Carter’s baby was laid as an egg, which has all sorts of distressing biological implications.

I think that one of the reasons why the “save the princess” trope hasn’t really worked its way into tabletop culture is because it would bring too much focus on one character. A group saving the princess is fine, but it’s much more rewarding for one hero and one princess to fall in love. Most players aren’t interested in one player’s romance with an NPC and most players are magnanimous enough to forego a princess for the sake of other players.

I DID play a short D&D module once where we were supposed to save a baron’s daughter; she turned out to be a wolf-were and ate everyone.

-

Don’t kiss any naked women you come across in the dungeon. It usually results in a level drain.

-

Yeah, but what a level drain. Sure beats getting socked with some Enervation spell by a grouchy necromancer.

-

No, they’re lucky to get a loin cloth most of the time.

Remember In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords? Oh man did that one drive us players nuts. Nothing but a loincloth. One of the PCs tried to strangle a mushroom with it.

Suffice to say we were all a little too short for that ride.

-

Wow, did that module ever leave an impression. Railroaded into a situation where you lose all of your stuff– no player can forgive a Dungeon Master that does that to them!

“…the default role playing adventurer is simply not cut from the same cloth as one of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s heroes. They are usually brazenly self-aggrandizing, greedy, and cunning– enough so that it is hard to feel bad for them when they come to a bad end. As dashing as they might be, they are ultimately little more than glorified orcs and brigands themselves.”

Hence the now-popular nickname, “murder hobos” 🙂