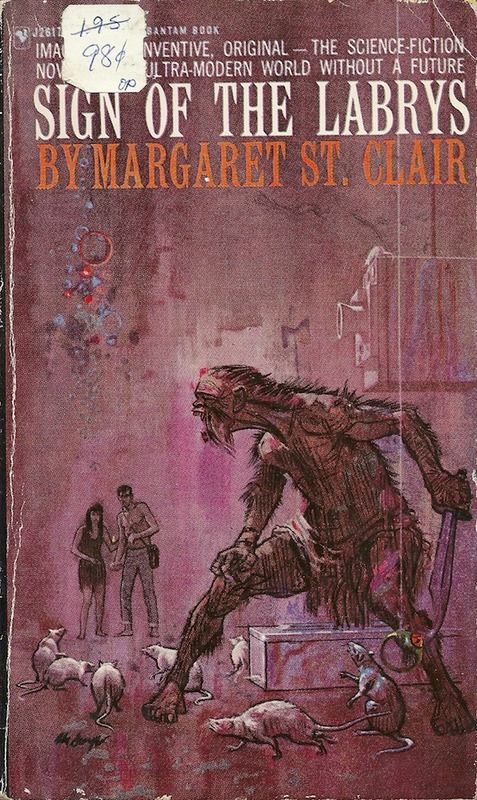

RETROSPECTIVE: Sign of the Labrys by Margaret St. Clair

Monday , 7, September 2015 Appendix N 8 Comments Margaret St. Clair’s formula for an original novel is to start with a realistic dystopian near-future, then layer in a major fantasy element for counter-point, incorporate widespread drug use and hallucinations, and finally… throw in at least two over-the-top science fiction elements that (in comic book fashion) fail to disrupt either the setting or the plot overmuch. It’s a potent combination that so dazzled her publishers, they could only explain her writing talent as being due to her feminine proximity to the primitive, her consciousness of the moon-pulls, and her Bene Gesserit-like awareness of “humankind’s obscure and ancient past.”

Margaret St. Clair’s formula for an original novel is to start with a realistic dystopian near-future, then layer in a major fantasy element for counter-point, incorporate widespread drug use and hallucinations, and finally… throw in at least two over-the-top science fiction elements that (in comic book fashion) fail to disrupt either the setting or the plot overmuch. It’s a potent combination that so dazzled her publishers, they could only explain her writing talent as being due to her feminine proximity to the primitive, her consciousness of the moon-pulls, and her Bene Gesserit-like awareness of “humankind’s obscure and ancient past.”

But it’s is more than just a great read. Within its pages is a contribution to tabletop gaming that is on par with Jack Vance’s magic in The Dying Earth, Poul Anderson’s law to chaos spectrum in Three Hearts and Three Lions, and the adventurer-conquer-king sequence that is at the heart of Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter and Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories. However, unlike those other inspirational works that played a significant role in the creation of the first fantasy role playing game, Margaret St. Clair’s influence is largely unrecognized.

Take for example this recent comment from game blogger DM David¹:

In the fantasies that inspired the game, no character explores a dungeon. At best, you can find elements of the dungeon crawl, such as treasure in the mummy’s tomb, orcs in Moria, traps in a Conan yarn, and so on.

This is just not the case. The archetypal Gygaxian dungeon really does have a literary antecedent, and it’s here in this book.² Each level has a different theme, from living areas for survivors of the apocalypse, to scientists and their unusual wandering monsters, and on to the VIP level where everyone is doped up on euph pills. Exploration is a key part of the plot as the lower levels are only connected by secret passages. At the same time– just like in the best good dungeon designs– there is also more than one way to get from one level to the next and sometimes ways to bypass levels entirely. Finally, the action of the novel is focused on exactly the sort of thing that consumes the bulk of so many game sessions to this day: a battle within a dungeon by two rival factions.

Taken together, it’s clear that some of the most offbeat aspects of what we take for granted in the standard gameplay of classic D&D and its decedents predates the game’s publication by over ten years. It’s uncanny, really. But there’s more. The really weird puzzles of the classic Infocom text adventures are anticipated here as well. If you’re wondering just how it is that the programmers at Infocom could come up with things like Zork’s Flood Control Dam #3 or Enchanter’s utterly devious Engine Room, Margaret St. Clair was coming up with puzzles like that almost two decades before 8-bit home computers became ubiquitous:

I had been been absently watching the movements of the goldfish. There was something oddly regular in the paths their swimming took. One group seemed, as far as I could judge, to mark out a series of figure eights, and another moved around the pool in a large ellipse.

I bent over and put one hand out directly in the path of an oncoming fish. It did not move aside or try to avoid my fingers. I closed my hand over it, brought my hand up through the water, and held my catch on my palm for the other two to look at. All this time there was not a wriggle or a twitch from the fish.

We exchanged glances. “It’s not alive,” Despoina said. She poked it with one finger. “Metal, or plastic with a metallic coat. What makes it move, then, Sam?”

I said slowly, “if something is tracing out lines of force on the underside of the pool…”

Ross’s eyes lit up. “I’ve seen something like that…. Wait– yes, I know now. There’s a matter transmitter under the bottom of the pool.” (page 98-99)

Figuring out how to operate this machine requires not just using a screwdriver to drain the pool, but also laying down in the correct position, arranging the fish just so, adjusting the dials and then pushing the right buttons. If something like getting the rocket to fly in the game of Myst ever struck you as being contrived, realize that that sort of thing was perfectly normal to an author like Margaret St. Claire.

And while she’s audacious enough to drop an uplifted dog and an anti-gravity pit into the middle of a fantasy story and then never revisit their implications again, her depiction of witches and witchcraft comprises a concentrated dose of the zeitgeist of the sixties. These are not cackling, broom riding hags. More like… incredibly groovy people intent on sticking it to the man through some kind of quirky insurrection. Here’s a sample of their shtick:

- Wicca are people who know things without being told. (page 92)

- We wicca know how to be happy even in a bad world. But we are not content with a bad world. (page 94)

- We wicca do not consider “the seeing” extra-sensory. (page 108)

No, these are not cultists intent on sacrificing children in order to summon some sort of horrific Elder God. At the same time, they are are rather unconventional folk. Their concepts of good and evil, right and wrong are quite fluid as this passage indicates:

“Despoina,” I said, “what did you mean when you said, “I am not above the law?”

“That there have been… witches who thought they were.”

“Who? You must have meant somebody.”

I could feel her considering whether to speak. “Kyra,” she said at last.

“Kyra? My half-sister? What did she do?”

“We didn’t know whether to admire her or to punish her. Kyra… loosed the yeasts.” (page 116)

The witch Despoina goes on to explain here that before the big blow-up, Kyra was a lab assistant at researching fungi for possible use in biological warfare. When she discovered a plague that was wiping out her guinea pigs, she chose on her own to unleash it on an unsuspecting humanity. The hero is of course shocked by this revelation.

“Consider the situation, Sam. Have you forgotten? Nuclear war seemed absolutely inevitable. Nobody knew from day to day– from hour to hour– when it would begin. We lived in terror, terror which was sure to accomplish itself. Nobody even dared to hope for a quick death.

“Kyra realized what had come into her hands. She acted. She took on her shoulders a terrible responsibility; she assumed a dreadful guilt. She knew that plagues are never universally fatal. She decided it was better that nine men out of ten should die, than that all men should.” (page 117)

The leaders of the Wicca folk did not necessarily disagree with the reasoning of this rogue witch. They mainly took umbrage at the fact that the leaders of the coven were not consulted before she killed countless numbers of innocent people. It’s only because this character unilaterally chose to bring about a plague-fueled apocalypse that she must be punished with exile to the science level of the dungeon more or less forever.

It’s hard to fathom people blithely justifying this level of death and destruction in order to “save” the world. This is so rotten in fact, if there was some sort of government agency or something that wanted to hunt them down and remove their ability to pose a threat, well… that would strike me as a perfectly rational response. And if I, like this protagonist, had grown up in the pre-plague world and then seen practically everything I’d known destroyed by a horrible diseases… I’m not sure how charitable I could really be to the person that was responsible for it. The protagonist, though… he doesn’t really struggle all that much with any of this.

This sort of thing really strains my capacity to suspend disbelief. Part of me wants to go back in time and tell the author that she’s writing this wrong. All she had to do was change the big reveal to show that it was some paranoid war monger straight out of Dr. Strangelove that had inadvertently released the plagues in an attempt to bring down the Soviet Union. The persecuted witches of the world could then be united in a heroic attempt to keep the totalitarian thugs from wiping them while they work out an antidote. Those are the sort of changes that would have to be made if everything was going to work out like it does in the movies.

But given that Margaret St. Clair was a devotee of Wicca, she knew precisely what she had to do to convey these sorts of people correctly.³ And witches should be attractive, seductive, and above all confusing; whether it’s in Hansel and Gretel, MacBeth, or The Broken Sword, they make the abandonment of common sense seem like a good idea even as they blur the dividing line between right and wrong. If they’re going to play to type, they should ultimately be able to make everything from the most cold-hearted revenge to the most brutal mass killing seem good and right and smart and sexy all at once– and the sultry, red-headed Desmoina really does manage to pull this off. Her blasé attitude towards the murder of ninety percent of mankind is actually right in line with the subject matter even if it goes against the grain of standard conventions of fantasy adventure.

No, after thinking this over, there is really not one thing I’d change about this book. From the publisher’s bizarre back cover blurb to the original inspiration of the Gygaxian megadungeon, from the drug infused apocalypse to the bizarre mixing and matching of science fiction and fantasy elements, this book is a masterpiece. There’s something intensely satisfying about the fact that conventions in tabletop games that we take for granted today sprang from something that was so fiercely original, sure. But this is a book that is so weird on so many levels that it really shouldn’t even exist. That’s why it’s so awesome.

—

¹ See 4 popular beliefs Dungeons & Dragons defied in the 70s for the complete post on this.

² Blog of Holding has more on this point: “It is interesting to note that just going down a set of stairs doesn’t guarantee that you’re going into a deeper ‘level’: a complex that’s 150 feet deep, and composed of several tiers, can be considered a single level if it’s part of the same ecosystem. And that is, I think, how early dungeons were designed. Each level was its own conceptual unit: it might or might not be composed of several floors. The author goes on to explain something else puzzling about Gygaxian dungeon design: levels aren’t always stacked one above another.”

³ Andrew Liptak at Kirkus says, “she and her husband led a comfortable life in California, where they owned a house with an extensive library, gardened and became Wiccans shortly after its introduction in the 1950s.”

I never knew this about dungeon antecedents. Thanks again for a great Appendix N series.

Excellent review. I’m fairly well-read in the Appendix N canon, but this one I’ve never seen.

The Gygaxian dungeon in this book itself has a literary antecedent in the form on Dante’s Inferno. It’s not just that the levels of the descent parallel those of the Inferno, which might be put down to literary “borrowing”, but the concluding line of the book (Where we came forth, and once more saw the stars) is a huge neon sign calling attention to the earlier work.