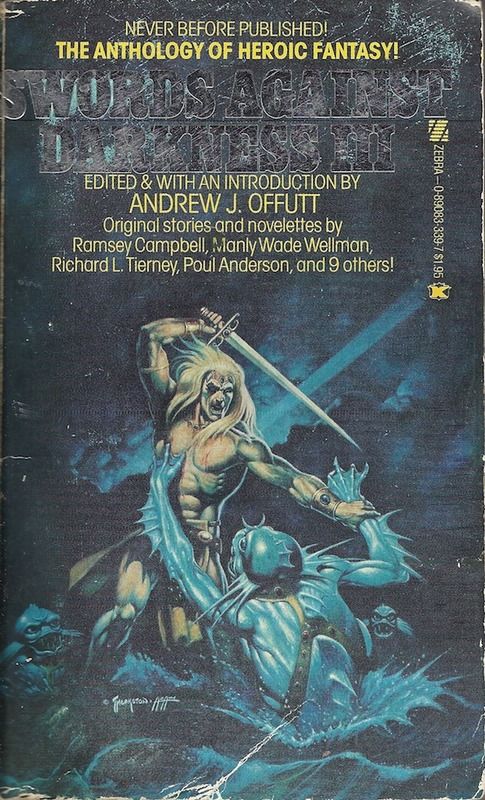

RETROSPECTIVE: Swords Against Darkness III edited by Andrew J. Offutt

Monday , 13, July 2015 Appendix N 9 Comments While this book was published too late to have any impact on the design of the initial iteration of Dungeons & Dragons, it nevertheless merited being singled out in Gary Gygax’s list of inspirational reading that appeared in his 1979 AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. Given the wide range of authors presented here, this collection preserves a snapshot of what a significant subgenre of fantasy was like just as roleplaying was on the verge of becoming a minor craze. And it’s not really that big of a surprise that the influential game designer could get behind a volume like this, either. The sort of situations detailed in the stories here are very much in line with the sort of things people deal with in the course of typical game sessions.

While this book was published too late to have any impact on the design of the initial iteration of Dungeons & Dragons, it nevertheless merited being singled out in Gary Gygax’s list of inspirational reading that appeared in his 1979 AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide. Given the wide range of authors presented here, this collection preserves a snapshot of what a significant subgenre of fantasy was like just as roleplaying was on the verge of becoming a minor craze. And it’s not really that big of a surprise that the influential game designer could get behind a volume like this, either. The sort of situations detailed in the stories here are very much in line with the sort of things people deal with in the course of typical game sessions.

And that’s the thing that really sets this volume apart from the other entries on the Appendix N list. When people sit down at a table to throw some dice and have an adventure, you simply do not see the sorts of worlds and ideas that turn up in so many of the other Appendix N books. You don’t see the weirdness of Jack Vance’s far future Dying Earth setting. You don’t see “salt of the earth” barbarians cut from the same cloth as Robert E. Howard’s Conan. You don’t experience the cosmic horror of an H. P. Lovecraft. You don’t see any Edgar Rice Burroughs type characters that punch commies and walk off with a beautiful princess, either.

Sure, there are games that focus entirely on those properties. But the claim that those works could somehow end up inspiring the original fantasy roleplaying game is actually hard to comprehend today. They’re just so… different. Really, the stuff of most D&D sessions is going to be more in line with the sort of derivative swords and sorcery that you can easily find in collections like this. A lot of people have never even heard of the “heroic fantasy” genre that this collection promises, but many of them will immediately recognize it when they read this book– it survives to this day at countless tabletops!

To hear Andrew J. Offutt describe it, almost everyone involved in writing fantasy fiction during this period seemed to be in touch with each other. It comes off as a very personal and fairly diverse scene. Offutt is calling up Ramsey Campbell so that he can teach the guy’s wife how to say, “bye y’all” in an authentic Kentucky drawl. Marrion Zimmer Bradley let him know that she was mildly insulted that she was not personally invited to contribute to the first volume this series. Poul Anderson comes off as being at least as much of a hobbyist as he is a professional; he could have simply retyped an old letter for this volume, but he cared enough to turn it into a full fledged essay.

And if I did have to single out one work from this collection that is most relevant to gamers it would be Poul Anderson’s piece, “On Thud and Blunder.” It includes a critique of the most common errors in heroic fantasy writing and explains how getting the facts and the history correct not only makes things more realistic, but also opens the door to all manner of interesting plot hooks. He addresses everything from economics to religion, warrior women and disease– not to mention armor penetration, two handed swords, and poisoned weapons, too. Gamers have of course been arguing about these topics for decades, but hearing the author of The Broken Sword weigh in on them is just plain fantastic.

This piece has “Gygax” written all over it, too. Yes, he is the person that wrote in the Dungeon Masters Guide that “the location of a hit or wound, the sort of damage done, sprains, breaks, and dislocations are not the stuff of heroic fantasy.” But he is also the guy the included elaborate tables for random ailments, and that made sure to mention that flag lily was a component in medieval cures for venereal disease. As controversial as some of his game design choices were, I think Anderson’s piece was something that he nevertheless took fairly seriously. After all, he was the sort of guy that would devote six pages to pole arm nomenclature in Unearthed Arcana.

Especially sobering, however, is Anderson’s warning to his fellow writers:

A small minority of heroic fantasy stories is set in real historical milieus, where the facts provide a degree of control– though howling errors remain all too easy to make. Most members of the genre, however, take place in an imaginary world. It may be a pre-glacial civilization like Howard’s, an altered time-line like Kurtz’s, another planet like Eddison’s, a remote future like Vance’s, a completely invented universe like Dunsany’s, or what have you; the point is, nobody pretends this is aught but a Never-never land, wherein the author is free to arrange geography, history, and the laws of nature to suit himself. Given that freedom, far too many writers nowadays have supposed that anything whatsoever goes, that practical day-to-day details are of no importance and hence they, the writers, have no homework to do before they start spinning their yarns…. If our field becomes swamped with this kind of garbage, readers are going to go elsewhere for entertainment and there will be no more heroic fantasy. (pages 272-273)

Heroic fantasy fiction did pretty well disappear in the following decade. But Poul Anderson’s craving for verisimilitude found a home among tabletop game design. Indeed, the eighties were a fairly well a battleground wherein every new roleplaying product had to be bigger and more comprehensive than the last. Realism was the watchword of gamers in general and everything from falling rules in AD&D to the physics of ejection seats in Car Wars was hotly debated.

Of course, by the nineties the typical gamer’s experience both with roleplaying games and the books that inspired them could be summed up in the idea of an action hero racing down a hallway to pick up a first aid kit that instantaneously replenished his hit points. And by now, arguments about realism are often relegated how fine the 3D graphics are.

I haven’t noticed tabletop gamers to be either excessively outraged about this trend, though. Far from being consumed with nostalgia, board gamers are quite happy with the shorter playing times and wider audiences that Euro gamer bring to the table. And while classic hex and chit war games still get played quite a bit, war gamers as a group have taken to the possibilities that block games, card driven strategy games, and euro game design elements have opened up for them. If the essence of a conflict can be more readily experienced half the play time and a learning curve that’s not nearly as steep, most gamers are willing to give it a shot.

Is realism passé in gaming? It depends on the genre. Where it counts, though, the realism has to bring something to overall experience. And it cannot anymore come at the expense of either gameplay or accessibility. With computer gaming being ubiquitous and with so many demands on our attention, designers simply cannot afford extraneous detail or complexity like the could back in the eighties. And while I still want to get those old classics played like they deserve, I have to admit… we seem to be entering a game design renaissance. We have a lot of great gaming to look forward to.

—

In order to assess just how relevant these stories were to tabletop fantasy roleplaying games, I reviewed them to see how well they fit with the requirements of the typical campaign. Game masters constructing their own settings may find these notes helpful in stocking their wilderness maps.

“The Pit of Wings” by Ramsey Campbell — This story opens up with a brief wilderness sequence, but contact with civilization here means encountering injustice that cannot be ignored by goodhearted barbarian types. In the inevitable clash, combat doesn’t have to be initiated by the stock standard reaction roll and initiative sequence. Roleplaying the exchange of escalating insults can provide for far more entertaining gameplay. Similarly, “boss” monsters can be more than just a few attack abilities attached to a pile of hit points. It’s possible for them to break the scope of the usual combat systems. The end game here demonstrates how the monster itself can be described through a set of three linked combat situations.

“The Sword of Spartacus” by Richard L. Tierney — This one is just plain awesome– exactly the sort of story that Poul Anderson was advocating in his essay. While the plot would be difficult to adapt to a tabletop game session, it could nevertheless serve as a backstory for someone that wants to play an ex-gladiator that’s destined for greatness. It’s loaded with gaming tropes, though: druids, Etruscan sorcery, relics of heroes from a previous age, undead wizards, and Cthulhu-style demons summoned through gates. The thing that takes the cake here is the idea that ordinary sporting events might have been inherited from people that had very specific religious rituals in mind when they developed them. If you’re looking for a game setting the weaves real history with the supernatural, this is an excellent resource.

“Servitude” by Wayne Hooks — This short piece is all about a cursed armband that forces its wearer to kill. The more powerful and influential the victims, the more feelings of love it pumps into the wearer. This produces a state of near invincibility, but the longer it’s been since it was satisfied, the harder it is to resist.

“Descales’ Skull” by David C. Smith — Wishes are a perennial element of classic fantasy roleplaying and this story presents an intriguing way to gain one: by acquiring and reassembling the skull bones of a dead sorcerer. Seeing as having the consequences of the wish blow up in their faces and lead the player character(s) straight to hell runs against the general gaming requirements of player autonomy, I would recommend having some other taint factor or mental disadvantage be the consequence of trafficking with these sorts of evil beings.

“In the Balance” by Tanith Lee — This short but striking piece presents a world where the discipline of magic is controlled by a monastic order and restricted by a range of moral precepts. While tests ranging from the Gom Jabbar to the Kobayashi Maru are a staple of genre fiction, having one that depends upon the content of your character from the standpoint of traditional morality is rather unusual.

“Tower of Darkness” by David Madison — Small towns and cities with some kind of local trouble are a classic gaming trope, and every campaign map could stand to have a few of those sprinkled around. In this story we get one such town where the people are known to be sun worshipers. When the adventurers arrive at nightfall, they find all the inns locked up and no one will talk to them… until they come upon a member of a group of moon worshipers that offers them hospitality. You can probably see where this one is going, but this whole situation will certainly give your players something to argue about. Not to mention a great chance to improve their status with the locals.

“The Mantichore” by David Drake — The idea that a Manticore could be worth this much of a scenario as we see in this story is almost hard to imagine. It’s not just that fantasy roleplaying games are generally set in worlds were fantastic creatures are merely a fact of life, either. Most hardcore dungeon crawlers can immediately identify a creature you’re describing based only on the fact that they have the exact same Monster Manual pictures in their head as you do. Big finale monsters from classic modules are well known even to people that haven’t played them because those same critters have been recycled into later products and magazine articles. To get something to happen in your game that’s even remotely like this story, the players will have to be facing something that is genuinely unknown, they will have to have conflicting rumors on it, and they will have to see evidence of its activities before they get to encountering it.

“Revenant” by Kathleen Resch — The depiction of vampires as the quintessential bad boyfriend is something that goes back further than you might think.

“Rite of Kings” by John DeCles — The story here makes for a thought-provoking read, but its core element would normally be a disaster at the table top. The protagonist has to make a series of three choices, based on nearly no information. They don’t really even qualify as real riddles, but are more of an opportunity to put the guy’s character flaws on display so that his final comeuppance can have sufficient punch. In a tabletop role-playing scenario, giving the players a chance to find enough clues that they could have a chance at making an informed choice at these junctures would help address some of the issues with this. Having each choice impact the scenario in such a way as to not make it unwinnable or impossible to walk away from would be another thing players would tend to expect. Nevertheless, this is so arbitrary and the number of permutations here are so great, I’m not sure salvaging his sort of thing is really even worth the effort.

“The Mating Web” by Robert E. Vardeman — In spite of their prominence in Tolkien’s lore, spiders are often treated as mere vermin in tabletop fantasy roleplaying games. And while cutesy attempts to rework classic monsters into misunderstood lonely hearts tends to rub me the wrong way, the treatment we get here is not only a good read, it is also eminently gameable. This story makes for excellent inspiration on making something a little more out of an otherwise forgettable random wilderness encounter with a giant spider.

“The Guest of Dzinganji” by Manly Wade Wellman — Robot-like creations don’t have to be absent from your fantasy world. Gods don’t have to be invincible, either. This tale features the sole survivor of Atlantis who has killed three different gods with his sword of starmetal… and it rocks! Our games are not like this… and that’s too bad!

“The Hag” by Darrell Schweitzer — If there’s one thing players should know by now it’s that they should never kiss anyone they meed in a dungeon, no matter how beautiful they appear to be. Of course, if there’s something stupid to be done, there’s almost always one person crazy enough to give it a go, so players will naturally get involved with things best left alone. This particular situation could be thrown at any group that is making nice with a local noble, but the fact that everything culminates into a single individual facing a more or less unfair situation means that it’s not the best fit for typical play styles. Nevertheless, game masters looking for inspiration both for giving a backstory to cursed beings and to incorporating the devil or other demonic entities into play will find this tale worth a look.

“A Kingdom Won” by Geo W. Proctor — When an island people lose the artifact that protected them from the wrath of the gods, everything they have is set to sink into the sea in a matter of days. Without a hero to challenge an evil sorcerer, they will all die before their magic can give them the gills that they need in order to survive in a radically different environment. This could be a perfect opportunity for a bold adventurer to save a princess, win the day, and earn the undying gratitude of an entire people. But what if there is more to this opportunity than first appears…? And what the hero is about to participate in the origin story of a familiar fantasy creature…?

“Swordslinger” by M. A. Washil — The more renown the players gain, the more punks are liable to show up looking to pick a fight with them. Again, if you’re going to hassle players with this sort of thing, don’t forget to play out the dialog leading up to the challenge.

Wellman did a number of stories featuring Kardios for the S.A.D. anthologies. I think there were five in all. I wish Paizo or someone would publish them all together.

This brings back memories. Those were great articles and stories. Manticore is a favorite of mine. While Drake writes in sci fi, fantasy, etc. what he really writes is horror and this is damn good horror. I love the chill factor.

Thud and Blunder was better than great. What made me love it more was that my historically illiterate cousin thought that Gnort the Barbarian and his fifty pound broadsword was the great beginning to a story. Always hated that guy.

I have read a recent fantasy story that has a sword, ‘too heavy for a normal man to lift’. I cannot remember the story or author but that stood out like a sore thumb.

Manly Wade Wellman is I think the best fantasy writer few have heard about. His stories all evoke a very real and believable universe.

This is chock full of great ideas for rpgs.