I’ve long been mystified at the incredible range and diversity of literature that roleplaying game designers of the seventies seemed to take for granted as being common knowledge. How is it that they seemed fluent in so many obscure authors, many of which were writing more than half a century before…? Compared with my experience growing up in the eighties, I just wouldn’t see a lot of the classic authors on the shelf at the local B. Dalton’s. Libraries would be loaded with Piers Anthony and Anne McCaffrey, but they would have almost nothing from the Gary Gygax’s Appendix N list. Except for a selection of the “big three” of science fiction– Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke– there would be very little fantasy and science fiction on the shelves from before 1970. What happened?!

I’ve long been mystified at the incredible range and diversity of literature that roleplaying game designers of the seventies seemed to take for granted as being common knowledge. How is it that they seemed fluent in so many obscure authors, many of which were writing more than half a century before…? Compared with my experience growing up in the eighties, I just wouldn’t see a lot of the classic authors on the shelf at the local B. Dalton’s. Libraries would be loaded with Piers Anthony and Anne McCaffrey, but they would have almost nothing from the Gary Gygax’s Appendix N list. Except for a selection of the “big three” of science fiction– Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke– there would be very little fantasy and science fiction on the shelves from before 1970. What happened?!

Part of the answer to this has to do with the fact that great authors and good books just seemed to stay in print longer back then. A. Merritt is all but forgotten now, for example– and sure, it’s no surprise to see his works dominating Avon’s paperback lineup in 1951. But Merritt’s work stayed in print on into the late sixties. His books would have been on the rack right next to classics like The Foundation Trilogy and Glory Road.¹

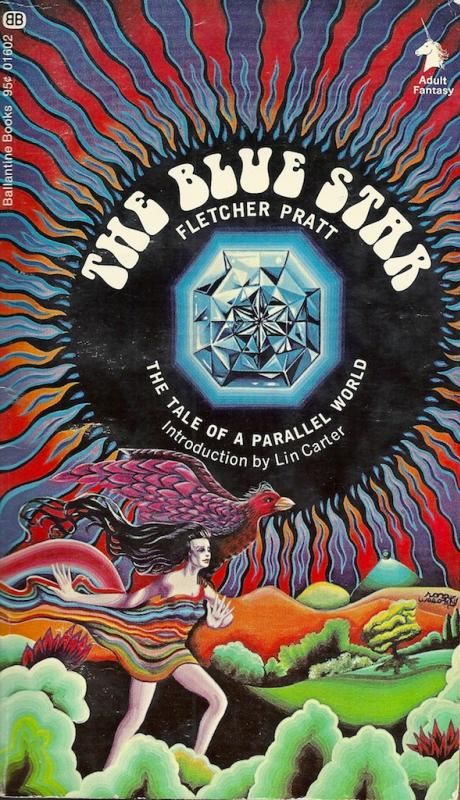

Coupled with this trend would be the sort of intentional literary archaeology embodied by Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series. In the wake of The Lord of the Rings’ runaway success there was a noticeable uptick in demand for serious works fantasy and Lin Carter scoured the stacks for anything that could meet it.² Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star is a prime example of this: it was an obscure work published in 1952 as part of an anthology. And it was hand picked by Lin Carter to inaugurate the new line of books that targeted an “adult audience” that craved “fantasy novels of adult calibre.”³

And boy does that ever sum up the nature of this book. It is a far cry from anything I’ve read from the old pulp magazines. Oh, it’s not a ponderous slog like Willam Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, but it clearly isn’t kid stuff… and it does take a while to get into what Pratt is serving up. If you wanted a breezy bit of swords and sorcery action, then this isn’t it! It’s like, well… Downton Abbey, but with witchcraft. The cultures, characters, religions, and intrigues are all fully realized and impact every turn of the plot. And this is not written for children, either. Just like the wildly popular television series, rape is something of a recurring theme. And though we don’t get a lot of gory details when it becomes a major plot element, it does tend to create a much harsher tone than what you typically get in the average fantasy novel. It’s different, but it’s a great book to read if you want to see what fantasy could be like in the absence of Tolkien’s overwhelming influence.

For those wanting to adapt Pratt’s approach to witchcraft into their own tabletop adventures, the biggest factor in how it is premised here is the fact that it is a hereditary ability. Powerful interests keep records of this sort of thing– and see to it that that ecclesiastical authorities don’t catch wind of who needs to be watched. Latent abilities become active only after the witch has lost her virginity⁴, and with the titular Blue Star she can bestow the ability to read minds upon her lover. This dangerous alliance is reminiscent of Ron Edwards’s game Sorcerer. It’s both personal and interpersonal and quite unlike the more common portrayal of magic as being little more than re-skinned technology.

Rodvard shivered slightly. Lalette said; “Open your jacket,” and when he had done so, hung the jewel round his neck on his thin gold chain.

“Now I will tell you as I have been taught,” she said, “that while you wear this jewel, you are of the witch-families, and can read the thoughts of those in whose eyes you look keenly. But only while you are my man and lover, for that power is yours through me. If you are unfaithful to me, it will become for you only a piece of glass; and if you do not give it up once I ask it back, there will lie upon you and it a deadly witchery, so that you can never rest again.” (page 28)

And that bit about him having to remain true to her in order to keep his new gifts is not a bluff. If you’re involved in “the great marriage” with a practitioner of “the art”, the witch is going to know if you cheat on her:

…a flash of lightning wrote in letters of fire across the inside of her mind the words Will you go with me now? and though there was no meaning in what they said, she understood that it told the unfaithfulness of her lover. (page 109)

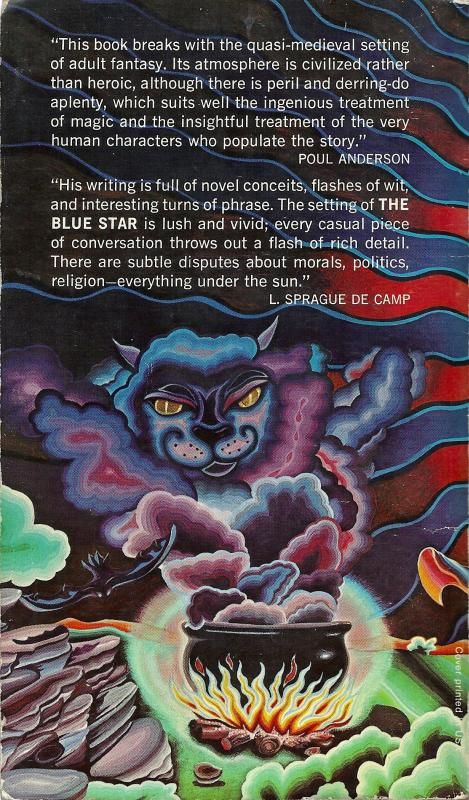

This is of course unlike any fictional treatment of witchcraft that I have ever seen. There is a lot of implications to setting it up this way, and everything the action and the setting is derived from this. But if you do like the more traditional approach to witches, that’s here, too– right down to the ugly old woman with the feline familiar and sinister cauldron:

She was fat and one eye looked off at the wrong angle, but Rodvard was in a state not to care if she had worn on her brow the mark of evil. He flopped on the straw-bed. There was only one window, at the other end; the couple whispered under it, after which the housewife set a pot on the fire. Rodvard saw a big striped cat that marched back and forth, back and forth, beside the straw-bed, and it gave him a sense of nameless unease. The woman paid no attention, only stirring the pot as she cast in an herb or two, and muttering to herself.

Curtains came down his eyes, though not that precisely, neither; he lay in a kind of suspension of life, while the steam of the pot seemed to spread toward filling the room. Time hung; then the potion must be ready, for through half-closed lids Rodvard could see he lurch toward him in a manner somewhat odd. Yet it was not til she reached the very side of the bed and lifted his head in the crook of one ark, which pressing toward his lips the small earthen bowl, that a tired mind realized he should not from his position been able to see her at all. A mystery; the pendulous face opened on gapped teeth; “Take it now my prettyboy, take it.”

The liquid was hot and very bitter on the lips, but as the first drops touched Rodvard’s tongue, the cat in the background emitted a scream that cut like a rusty saw. The woman jerked violently, spilling the stuff so it scalded him all down the chin and chest as she let go. She swung round squawking something that sounded like “Posekshus!” at the animal. Rodvard struggled desperately as in a nightmare, unable to move a muscle no more than if he had been carved out of stone, realizing horribly that he had been bewitched. He wanted to vomit and could not; the cottage-wife turned back toward him with an expression little beautiful. (page 96)

The book tends to focus primarily on Rodvard and what he does with his ability to read thoughts. It provides him with significant edge in the political arena, but when you’re a penniless clerk it really doesn’t do that much to turn you into a superman. The old hag, for example is far more concerned with offending Rodvard’s witch than anything else. And rightly so, Lalette seems to be able to dole out potent curses when she’s pressed sufficiently:

“It is the watch to daybreak. No one aboard will ever know.”

“No, no, I will not,” replied Lalette, (feeling all her strength melting), though he did not try to hold her hands or put any compulsion on her but that of the half-sobbing warm close contact, (somehow sweet, so that she could hardly bear it, and anything, anything was better than this silent struggle). No water; she let a little moisture dribble out of he averted lips into the palm of one hand, and with the forfinger of the other traced the pattern above one ear in his hair, she did not know whether well or badly. “Go!” she said, fierce and low (noting, as though it were something in which she had no part how the green fire seemed to run through his hair and to be absorbed into his head). “Go and return no more.”

The breathing relaxed, the pressure ceased. She heard his feet shamble toward the door and the tiny creak again before realizing; then leaped like a bird to the heaving deck, nightrobed as she was. Too late: even from the door of the cabin, she could see the faint lantern-gleam on Tegval’s back as he took the last stumbling steps to the rail and over into a white curl of foam.

A whistle blew; someone cried: “A man lost!” and Lalette was instantly and horribly seasick. (page 130)

Very little of this sort of action appears in the book, however. Even when it does happen, it’s only in response to a crisis situation. The consequences of being an outcast on the run from the civil authorities are apparently too great for her to act with impunity. She never achieves anything like the stature of a Morgan Le Fay and one necessarily wonders what she could have accomplished had she had the opportunity to select a more capable man as a mate. With this particular specimen in tow, it’s much more important for Lalette that she gain some sort of refuge and cover than anything else.

The abilities conferred by a Blue Star are a significant and secret trump card for whoever would seize control of the state, however, so she and Rodvard are necessarily of interest to the sort of people that could actually leverage their talents to good effect at the domain level. But the ability to read minds seems to get reworked over the course of the book to be much more restricted– only about reading particular types of emotion:

“You bear a Blue Star.”

(It was not a question, but a statement; Rodvard did not feel an answer called for, therefore made none.)

“Be warned,” said the second Initiate, “that it is somewhat less potent here than elsewhere, since it is the command of the God of love that all shall deal in truth, and therefore there is little hidden for it to reveal.”

“But I–” began Rodvard. The Initiate held up his hand for silence:

“Doubtless you thought that your charm permitted you to read all that is in the mind. Learn, young man, that the value of this stone being founded on witchery and evil, will teach you only the thoughts that stem from the Evil god; as hatred, licentiousness, cruelty, deception, murder.” (page 159)

And so it is, except for a passage early on where Rodvard reads someone’s mind as if he could see a running internal monologue that’s in English, every other scene involving the use of the ability consists more of him sensing the nuances of more negative emotions of related to lust or a desire for violence or other wrongdoing.

The various political factions and religions depicted in the book really do seem to be thought through, though. They are their own thing, and not a thinly veiled attempt to rake a particular real world group over the coals. In fact, none of them stand out as being the “good guys.” There is a baseline culture that has a strong aristocracy and a strict ecclesiastical authority. Within it is sort of a “cryptic alliance” or secret society that is intent on overthrowing the upper crust there. This country is at war with a nation that blends aspects of gnosticism and communism into its own weird society. Its religion is not entirely bunk, but clearly grants some real-world abilities especially in regards to witchcraft. And devotees of this ideology also exist within the base culture along at least one other significant ethnic group.

The various political factions and religions depicted in the book really do seem to be thought through, though. They are their own thing, and not a thinly veiled attempt to rake a particular real world group over the coals. In fact, none of them stand out as being the “good guys.” There is a baseline culture that has a strong aristocracy and a strict ecclesiastical authority. Within it is sort of a “cryptic alliance” or secret society that is intent on overthrowing the upper crust there. This country is at war with a nation that blends aspects of gnosticism and communism into its own weird society. Its religion is not entirely bunk, but clearly grants some real-world abilities especially in regards to witchcraft. And devotees of this ideology also exist within the base culture along at least one other significant ethnic group.

Fletcher Pratt’s world building is much more the focus of this book than any of the usual tropes of adventure fiction. He in fact turns more than a few of those tropes on their head: for instance, when Rodvard manages to somehow rescue Lalette from a life of involuntary prostitution, he does not earn her undying gratitude in the process.⁵ And the things Pratt emphasizes are of a far different stripe than what Tolkien tends to focus on: you don’t see any elaborate maps or genealogies or myths or histories or epic poetry here. The investment is almost entirely within the realm of culture, human institutions, ideas, and beliefs.

Before reading this, I didn’t even realize that I would be interested in something like that. And I had to get about a third of the way through it before I could fully grasp what it was that I was getting into. Having completed the book now, it’s hard not to wonder about what we’ve lost in the transition to a more more derivative and formulaic approach to fantasy fiction. But I have to admit, this Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series was an incredibly good idea. I’m glad that it happened… and I’m even more glad that I can get these books today. Even if it’s not that big of a surprise that this sort of fantasy wasn’t overwhelmingly popular and failed to persist too long on the shelf at book stores and libraries.

¹ See the Avon pages in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database for details: 1951, 1966, 1967, and 1968. (Thanks to Wayne Rossi and Guy Fullerton for pointing me toward this useful tool!) Also note that in the seventies, Merritt’s books would have been coming out right alongside Zelazny’s Amber series.

² See Lin Carter and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series over at Black Gate for details.

³ This is from Lin Carter’s introduction to The Blue Star, written in 1969: “Some of the most sophisticated novels of the last two centuries have been fantastic romances of adventure and ideas; books which few, if any, children would be capable of appreciating. The astonishing success of J. R. R. Tolkien’sThe Lord of the Rings, and Ballantine Books’ editions of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy and the extraordinary fantastic novels of E. R. Eddison have proved beyond a doubt that an enthusiastic adult audience exists for fantasy novels of adult calibre. The trouble is that many of these books are long out of print, scarce and rare, known only to a handful of collectors and connoisseurs. Some of them have never been published in the United States and are difficult to find.”

⁴ Lin Carter also points out in his introduction that the mother loses the ability to work witchcraft at the moment that her daughter gets it.

⁵ Given that the relationship began with rape and later moved on to rank unfaithfulness, this is hardly a surprise. From start to finish, this couple never follows the standard script for fairy-tale romance. That is to some extent both refreshing and disappointing at the same time.

I read that story about forty years ago and it was too dense for my adolescent mind. I’ll give it another chance.