RETROSPECTIVE: The Face in the Abyss by A. Merritt

Wednesday , 20, January 2016 Appendix N 3 Comments What is it that makes weird fiction so weird…?

What is it that makes weird fiction so weird…?

One factor that played into it was that people in the opening decades of the twentieth century might think you weren’t normal if you liked that sort of thing. A “regular guy” like Edgar Rice Burroughs didn’t feel comfortable having his name associated with A Princess of Mars at the start, after all. There’s more to it than that, though. You see… just like people back then would write stories about light sabers and disintegration rays without really having the vocabulary for those things, so too would they concoct a whole range of strange tales without the benefit of the genre distinctions that we have today. Consequently, writers in the twenties and thirties could blithely mix elements from fantasy, science fiction, and horror without any regard to the conventions that would ultimately emerge as genre writing became more of a commodity.

Weird fiction is offbeat today for entirely different reasons than it was initially. And though you don’t have to read very much of it to get a glimpse of just how distinct the works of the old masters are in comparison to more recent and derivative works, most people are content to extrapolate backwards from old television and movies when they make their guesses about what they must have been like. Indeed, most generalizations made about the pulps today are nonsense, and people that think that their efforts at bending accepted rules of genre are somehow innovative have no idea how much their efforts pale in comparison to the best works of the pulp era.

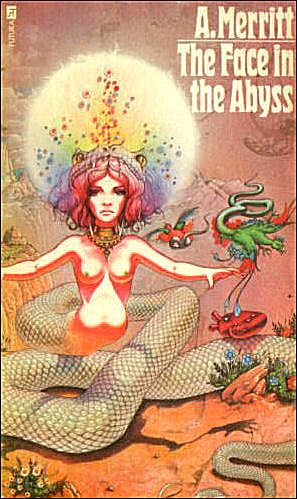

Take A. Merritt’s novelette The Face in the Abyss from 1923 as just one example. It opens with the promise of an Indiana Jones style treasure hunt in the heart of the Andean wilderness– a search for the ransom of Inca Atahualpa that was never paid to the conquistador Pizarro. But the unusual golden map leads the party of adventurers into some strange fairy realm. Before the first chapter is through there is a scene worthy of a Margaret Brundage cover. Then in the same context as”horns of Elfland dimly blowing” there are not just dinosaurs, but also genetically-engineered spider-men. Because the scientific term was not yet coined by Jack Williamson, so Merritt very nearly had to resort to poetry in order to describe it:

Might it not well be, then, that in Yu-Atlanchi dwelt those to whom the crucible of birth held no secrets; who could dip within it and mold from its contents what they would?

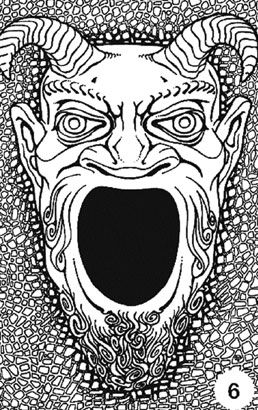

Finally, the central figure of the tale comes not from not from science or fairy, but from myth: the Snake Mother “may even be the germ of truth in the legend of Lilith, first wife of Adam, whom Eve ousted.” And the titular Face in the Abyss can only be described in biblical terms:

The Face looked at him from the far side of the cavern. Bodiless, its chin rested upon the floor. Colossal, its eyes of pale blue crystals were level with his. It was carved out of the same black stone as the walls, but within it was no faintest sparkle of the darting luminescences.

It was a man’s face and the face of a fallen angel’s in one;

Luciferean; imperious; ruthless—and beautiful. Upon its broad brows power was enthroned—power which could have been godlike in beneficence, had it so willed, but which had chosen instead the lot of Satan.

Weird fiction is thus at the intersection of history, fairy, myth, science, and (yes!) the bible. In Merritt’s handling, there’s a good dose of adventure and steamy romance mixed in as well, of course. And what’s more, there is even an element of the sort of gradually increasing terror that would later become the touchstone of H. P. Lovecraft’s best stories.

Weird fiction is thus at the intersection of history, fairy, myth, science, and (yes!) the bible. In Merritt’s handling, there’s a good dose of adventure and steamy romance mixed in as well, of course. And what’s more, there is even an element of the sort of gradually increasing terror that would later become the touchstone of H. P. Lovecraft’s best stories.

It’s awesome.

People today will find this story of especial interest due to its having provided the literary antecedent to the The Face of the Great Green Devil from the infamous AD&D module The Tomb of Horrors by Gary Gygax. But it’s important to note that A. Merritt was far from being an obscure pulp writer at the time that adventure was being published. Indeed, Merritt was such a significant figure in fantasy and science fiction fandom back then that for the 1980 Westercon someone dressed up as the Snake Mother character from this book. Topless, no less.

While it’s hard to imagine something like that happening in today’s convention scene, it’s actually even harder to imagine anyone writing like A. Merritt. His work really is that weird!

—

A. Merritt was born 131 years ago today on January 20, 1884.

Wow, cosplay before the obesity epidemic was a lot more scandalous than I expected.

Never read Merritt’s work so appreciate the review. The Moon Pool and The Metal Monster are available on Kindle for free